The congressional campaign of Rep. Mary Peltola in 2022 was truly remarkable in many ways. After being out of the political spotlight for years, Peltola emerged as a dark-horse candidate with an unknown brand among 48 names on a special primary ballot.

However, she quickly became the darling of the mainstream media, the Left, and even a few Republicans who were once fans of Congressman Don Young. While Peltola still enjoys a honeymoon period with the media, she has disappointed many Alaskans with her hard-left positions.

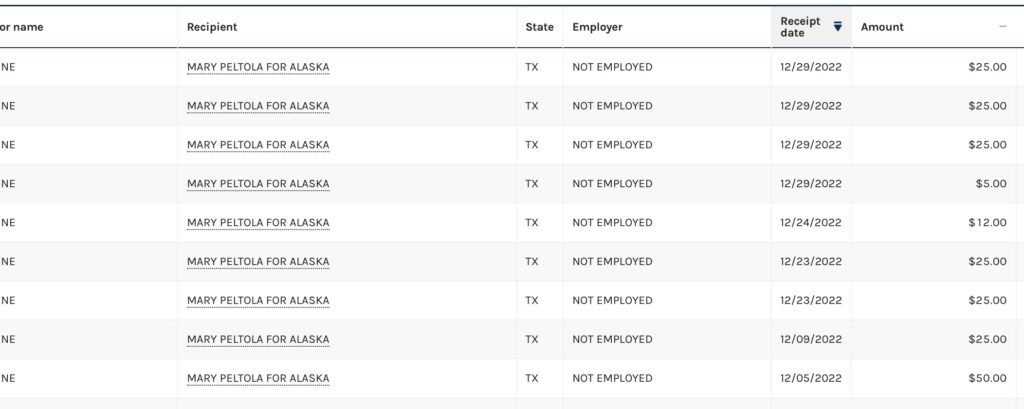

Unfortunately, a closer look at Peltola’s campaign donation list from 2022 reveals that she relied on the ActBlue fundraising platform, which is notorious for its use by many Democrat “fundraising mill” operations.

Peltola received thousands of small donations from a relatively small group of Americans who, according to records, appeared to be donating multiple times a day or week to Peltola over the course of less than a year, almost always in very modest amounts that added up over time.

Must Read Alaska has combed through thousands of Federal Election Commission listings of the donations that Rep. Mary Peltola received from outside Alaska through ActBlue during the 2022 election cycle. The donations came from all over the country, including Florida, California, Missouri, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, and elswhere. What’s more, many of the donors were elderly individuals, and most of them were not employed, according to FEC data obtained through ActBlue.

If we take these official records at face value, it appears that many senior citizens are spending their days hitting the “Donate Now” button repeatedly for political causes and candidates. The amounts that each one of these elderly donors are contributing add up to sometimes thousands of dollars a year.

To illustrate, here are a few examples of small-dollar donors (all elderly and from out-of-state) who fall into the “obsessive compulsive” category of frequent donations, where they’ve given to both ActBlue and Peltola, often donating multiple times per day over the course of many months. We are only using their initials and how many discrete donations they made in this 2021-2022 election cycle:

S.K.: 1,551 separate donations

G.C.: 5,008 separate donations

A.A.L.: 1,916 separate donations

J.B.: 1,590 separate donations

R.L.: 3,862 separate donations

P.C.: 1,520 separate donations

B.S.: 2,801 separate donations

P.P.: 9,482 separate donations

The pattern of the donations are similar to the type reported by journalist James O’Keefe and private investigator Kyle Corrigan, who separately spoke to a handful of these Americans who were listed as donors through ActBlue, only to learn that the elderly Americans had no idea they had donated the amounts listed by ActBlue and the Federal Election Commission — because they had not made those donations. Instead, it appears that ActBlue may be identifying elderly donors and then pushing dark money donations through their profiles.

This practice, if it is occurring, is known as “smurfing.” Smurfing, also called “structuring,” is how some launder money from a large transaction that is broken up into smaller transactions in order to avoid detection.

Could it be that these elderly contributors are being used as straw donors in a type of smurfing operation?

What O’Keefe and Corrigan found in their door-to-door research were that the donors knew they had made one or two small donations to a Democrat. They were, after all, Democrats. But they were floored to discover that they were credited with donating thousands of dollars.

Here’s an example of a person who has made an extraordinary number of contributions:

H.H. of New Mexico started donating to Mary Peltola on Sept. 15, 2022, and then made donations nearly every other day, including on Sept. 15, 16 (twice), 19, 20, 22, 25, 27, 29, 30 (twice), Oct. 4, 6, 12 (twice), 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 24, and following this pattern all the way to Dec. 31 when he made his final donation of the year.

As with the other obsessive-compulsive donors, he is listed as not employed. And as with so many others, he is elderly.

H.H. also was donating with excessive frequency to other causes through ActBlue. In December, 2022, long after the election was over, he made over 85 separate donations to ActBlue, for causes such as the “Let America Vote PAC,” “Stop Republicans,” “Progressive Turnout Project,” “Democratic Victory PAC,” “End Citizens United,” and other groups that use ActBlue for fundraising.

In November, H.H. made over 310 donations to ActBlue; this means he was making 10 donations a day on average. All of them were between $3 and $29.

But in the two-year election cycle of 2021-2022, H.H. made over 2,600 separate donations through Act Blue, an average of over 3.5 donations per day for two years. All of this donors contributions through ActBlue were small.

P.P., a middle-aged woman from Munster, Indiana, also made over 600 donations through ActBlue in December alone, after the election was over. Her total for 2021-2022 was over 9,200 separate donations. Many of the donations are as small as 30 cents. In the 2020 cycle, she also made what would be considered an unlikely number of donations.

Although there is no proof, only circumstantial evidence, that there is a type of donor-laundering operation going on in fundraising mills that are integrated with the ActBlue program, this is the kind of activity that might raise concerns from the FEC, which has been silent on the matter since O’Keefe raised the red flag last week.

A year ago, ActBlue was the subject of a complaint about alleged credit card fraud by a person who said that the political fundraising tool deducted hundreds of small contributions that the man did not authorize.

“The Complaint and Supplemental Complaint also state that ActBlue charged multiple transactions as ‘reoccurring’ when Complainant intended the contributions to be singular transactions.”

The FEC assigned a “low priority” to the complaint because the dollar amount was too low to rise to the level of concern to the commission.