By ALEXANDER DOLITSKY

Part II: Roosevelt’s approach to aiding the Soviets was cautious but intuitively optimistic

To help the Western Allies fight the Nazi war machine in Europe, in early 1941 U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced in the Congress a Lend-Lease bill titled “An Act Further to Promote the Defense of the United States.”

The bill was intensely debated throughout the United States, with the most strident opposition coming from isolationists and anti-Roosevelt Republicans.

Nevertheless, on March 11, 1941, Congress approved the Lend-Lease Act, granting to the president the plenary powers to sell, transfer title to, exchange, lease, lend, or arrange in whatever manner he deemed necessary the delivery of military materials or military information to the government of a friendly country, if its defense against aggression was vitally important for the defense of the United States.

The passing of the Lend-Lease Act was in effect an economic declaration of war against Nazi Germany and its Axis partners. Most Americans were prepared to take that risk rather than see Britain collapse, leaving the United States to face the Axis powers alone.

After the Nazi German invasion of the Soviet Union, the governments of Britain and the United States declared their support for the USSR in its struggle against fascist aggression.

On June 22, 1941, Winston Churchill, speaking over the radio, announced, “Hitler’s invasion of Russia was only a prelude to an invasion of the British Isles,” and, on June 23, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt made the statement to the media that “Hitler’s armies are today the chief dangers to the Americas.”

Roosevelt’s statement contained no distinct promise of aid to the Soviets but stated clearly the State Department’s policy. The next day, on June 24, 1941, the President announced at a press conference that the United States would give all possible help to the Soviet people in their struggle against Nazi Germany and its Axis partners.

That same day, Roosevelt released Soviet assets in American banks, which had been frozen after the Soviet attack on Finland on November 30, 1939; this enabled the Soviets immediately to purchase 59 fighter aircraft. Preliminary discussions between US, British, and Soviet officials on deliveries of arms and other vital supplies began on June 26, 1941.

A British credit line was subsequently opened on August 16, 1941, and arms deliveries from England were immediately initiated, with the American Lend-Lease principles as guidelines. Soon after the U.S.–Soviet Lend-Lease agreement was signed on June 11, 1942, Britain’s ongoing provision of materials to the Soviet Union was formalized in a British–Soviet Lend-Lease agreement signed on June 26.

Many conservatives in the United States argued vociferously against the U.S.–Soviet Pact, asserting that America’s aid should be disbursed only to proven friends, such as Great Britain and China. In congressional debates on the subject in late July and August, isolationists insisted that to aid the Soviet Union was to aid communism.

In June of 1941, U.S. Senator (later President, 1945‒54) Harry Truman expressed common American sentiments on Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union: “If we see that Germany is winning, we ought to help Russia, and if we see Russia is winning, we ought to help Germany, and that way let them kill as many as possible.”

At the same time, others thought the Russian front might be America’s salvation. In July of 1941, a public opinion poll indicated that 54 percent of Americans opposed Soviet aid, but by September those opposed registered only 44 percent, and those who favored helping the Soviet Union had risen to 49 percent.

Roosevelt’s approach to aiding the Soviets was cautious but intuitively optimistic. He distrusted them but did not think that they, in contrast to the Germans, intended to conquer Europe. He viewed Hitler’s armies as the chief threat to the Americas. Roosevelt calculated the Soviets would resist the German assault longer than anyone anticipated, which would help the British to fight the war, and perhaps preclude America’s entry into Europe and North Africa. The President relied heavily on the assessment of senior advisers Harry Lloyd Hopkins and Averell William Harriman, who urged him to bring the Soviet Union under Lend-Leaseagreement. But Roosevelt still held back.

In July of 1941, Roosevelt appointed two American special assistants, Harry Hopkins and Melvin Purvis, and Soviet Ambassador to the United States Constantine Oumansky to an intergovernmental committee on Soviet aid; he also dispatched his trusted aide Harry Hopkins to go to the Soviet Union in order to assess the Soviet military situation and talk with Soviet officials. After meeting with Stalin and other Soviet authorities, Hopkins came to the conclusion that the Soviets would withstand the German attack and cabled Washington his opinion to that effect. In early September of 1941, Roosevelt decided to send Averell Harriman, a significant investor in the Soviet Union since 1918, to Moscow as a special adviser on Lend-Lease matters. Harriman, along with British representatives, was charged with working out a temporary aid program.

Negotiating the US–Soviet Lend-Lease Agreement

From September 29 to October 1, 1941, representatives from Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States attended a conference in Moscow. There, a plan was drawn up for delivery of armaments, equipment, and foodstuffs to the Soviet Union. The USSR in turn agreed to provide strategic raw materials to Britain and the United States.

During the conference, Harriman for the first time suggested delivery of American aircraft to the Soviet Union via Alaska and Siberia, using American crews. Stalin initially rejected this idea outright, perhaps to avoid provoking Japan. Despite political tensions at the Moscow conference, on October 30, 1941, Roosevelt approved, and, on November 4, Stalin accepted, $1 billion in aid, to be repaid in 10 years, interest free.

Although the Soviet government was pleased with the aid package, its diplomats still complained that the Allies had taken no serious military actions against Germany, leaving the Soviet Union to continue to bear the brunt of the war alone.

The Soviets suggested that Britain and the United States open a second front in France or the Balkans or send troops through Iran, which the Soviets and British had jointly occupied in August of 1941 in order to preclude Germany from attacking Ukraine from the south. The Soviet government continued to insist that opening a second front in Europe would relieve pressure from enemy attacks on the Eastern Front.

The Allies, however, were reluctant to initiate this plan at the time because of lack of available forces for a second front, due to Allied involvement in the Pacific and North African theaters. Churchill, Stalin, and Roosevelt, in tacit acknowledgment of the fact that they had not yet reached agreement on joint war or peace aims, thus limited their 1941 pact to Lend-Lease support to the Soviet Union.

On July 7, 1941, a Soviet delegation flew from Vladivostok to Nome and then on to Kodiak and Seattle for secret talks with American officials regarding aircraft deliveries to the USSR and the feasibility of Pacific supply routes. The Soviet and American delegations discussed several possible routes for shipping planes and war materials to the USSR. The first was a sea route across the North Atlantic and around the North Cape to the ice-free Arctic ports of Murmansk and Archangelsk. This route was shorter but, by far, the more dangerous of those considered because of regular patrols in the area by the German Kriegsmarine (navy) and Luftwaffe (air force).

Another discussed route would transport the materials by ship across the Atlantic Ocean, around South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, and then north to the Iraqi port of Basra, where supplies would be loaded onto trains and trucks and transported to Soviet Central Asia and Azerbaijan via Iran. This route, too, had serious drawbacks—not only would the goods take too long to reach the USSR, the desert sands in Iran were notorious for infiltrating and ruining aircraft engines.

On October 1, 1941, the United States and the USSR signed their first Lend-Lease Protocol, eeffective from October 1, 1941, through June 30, 1942. The Soviet Union accepted most of the lend-lease terms, but specific details had yet to be worked out. On May 29, 1942, Vyacheslav Molotov, the Soviet Foreign Affairs Commissar and the right hand of Joseph Stalin on foreign affairs, arrived in the United States to discuss Lend-Lease matters.

It was the Soviet dignitary’s first official visit on American soil. Being cautious and uncertain in this formerly hostile country, Molotov carried in his luggage some sausages, a piece of black bread, and a pistol to defend his person if the need arose.

During Molotov’s visit, President Roosevelt raised two possibilities: (1) that American aircraft be flown to the USSR via Alaska and Siberia; and (2) that Soviet ships pick up Lend-Lease supplies from America’s West Coast ports for ferrying across the Pacific to Vladivostok and other Soviet Far Eastern ports—in addition to two other routes (the northern run to Murmansk and the Iran route) proposed earlier in July 1941. Roosevelt noted that by using the Alaska–Siberia air route, which would connect to the Trans-Siberian Railway, Lend-Lease supplies could more quickly and safely reach the Ural industrial complex around Magnitogorsk.

After careful consideration of various proposals, the best route for planes seemed to be via the US, Canada, Alaska, and Siberia. Although great distances were involved and the worst possible weather conditions would be encountered, the planes would be delivered in flying condition and the possibility of enemy interference would be remote. American support for the Alaska–Siberia (ALSIB) route was also based on the hope that, eventually, Siberian air bases would be used for bombing raids on Japan.

The Soviets, however, were hesitant to use this route, believing it to be too dangerous and impractical. It was also thought that remote Siberian cities would not be able to accommodate the busy air traffic and that the presence of Americans in the Soviet Far East would be unwanted. The Soviets were also afraid that the Pacific supply routes, and the ALSIB route in particular, might provoke Japanese military actions against the Soviet Union.

Nevertheless, faced with mounting losses on the sea run to Murmansk, and given the great distances involved in the Middle East route, in October 1941, the Soviet Union’s State Defense Committee decided to begin necessary preparatory work for the ALSIB Air Route and finally agreed to open it on August 3, 1942.

Two months prior to the opening of the ALSIB Air Route, the final Soviet–American Lend-Lease Agreement was signed in Washington, D.C., on June 11, 1942. The Agreement, titled “Agreement between Governments of the USSR and USA on Principles Employed to the Mutual Assistance in Fighting a War Against the Aggression,” stipulated:

The government of the United States will continue to supply the Soviet Union, in accordance with the United States Lend-Lease Act of March 11, 1941, with a defense material, services, and information. The USSR, after the completion of the war, must to return to the United States all those defense material that have not been destroyed, lost, or unused. On the other side, the USSR is obligated to assist the defense of the United States in providing a necessary material, services, privileges and information to the extent it is possible.

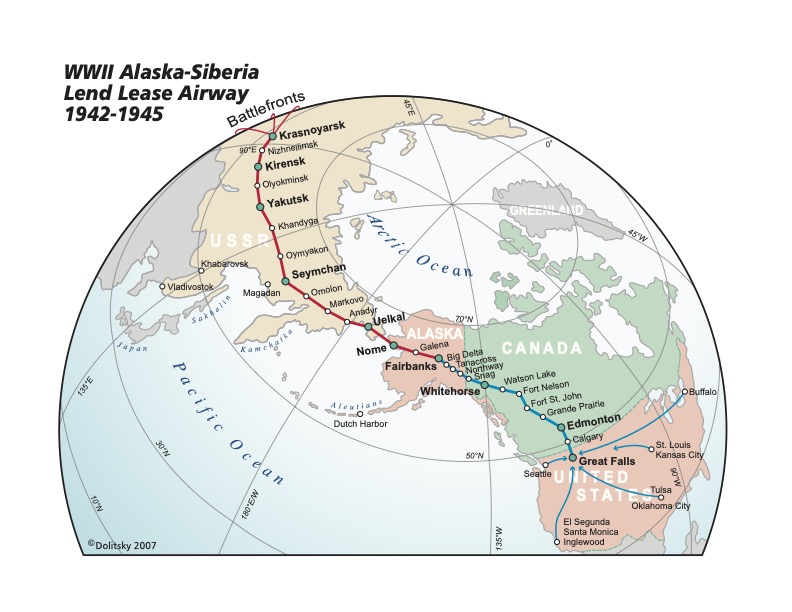

The ALSIB delivery route finally became a reality in August of 1942. A North American air transport route connecting Great Falls in Montana, Edmonton and Whitehorse in Canada, and Fairbanks, Galena, and Nome in Alaska was established and operational by mid-October. A major airfield constructed in Nome served as the jumping-off point for airplanes headed for Siberia. Once inside Siberia, planes continued on their long trip from Uelkal through Markovo, Seymchan, Yakutsk, Kirensk, and finally to Krasnoyarsk.

In Krasnoyarsk, pilots from combat units took over, flying the newly arrived aircraft westward via Omsk, Sverdlovsk, and Kazan to the Russian battlefronts. Over the program’s three years of operation, nearly 8,000 aircraft would be sent through Great Falls to Fairbanks’ Ladd Army Airfield for transfer to the Soviet Union, each crossing a total distance of almost 6,050 miles in harsh sub-Arctic and Arctic conditions. The distance over which combat planes were ferried from the manufacturing sites to the warfronts in Europe was even greater: 8,000–10,000 miles across 12 time zones.

Part 1 of this series is below. Part 3, Lend-lease and the Soviet mission in Alaska, will appear on Monday.

Alexander B. Dolitsky was born and raised in Kiev in the former Soviet Union. He received an M.A. in history from Kiev Pedagogical Institute, Ukraine, in 1976; an M.A. in anthropology and archaeology from Brown University in 1983; and was enroled in the Ph.D. program in Anthropology at Bryn Mawr College from 1983 to 1985, where he was also a lecturer in the Russian Center. In the U.S.S.R., he was a social studies teacher for three years, and an archaeologist for five years for the Ukranian Academy of Sciences. In 1978, he settled in the United States. Dolitsky visited Alaska for the first time in 1981, while conducting field research for graduate school at Brown. He lived first in Sitka in 1985 and then settled in Juneau in 1986. From 1985 to 1987, he was a U.S. Forest Service archaeologist and social scientist. He was an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Russian Studies at the University of Alaska Southeast from 1985 to 1999; Social Studies Instructor at the Alyeska Central School, Alaska Department of Education from 1988 to 2006; and has been the Director of the Alaska-Siberia Research Center (see www.aksrc.homestead.com) from 1990 to present. He has conducted about 30 field studies in various areas of the former Soviet Union (including Siberia), Central Asia, South America, Eastern Europe and the United States (including Alaska). Dolitsky has been a lecturer on the World Discoverer, Spirit of Oceanus, andClipper Odyssey vessels in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. He was the Project Manager for the WWII Alaska-Siberia Lend Lease Memorial, which was erected in Fairbanks in 2006. He has published extensively in the fields of anthropology, history, archaeology, and ethnography. His more recent publications include Fairy Tales and Myths of the Bering Strait Chukchi, Ancient Tales of Kamchatka; Tales and Legends of the Yupik Eskimos of Siberia; Old Russia in Modern America: Russian Old Believers in Alaska; Allies in Wartime: The Alaska-Siberia Airway During WWII; Spirit of the Siberian Tiger: Folktales of the Russian Far East; Living Wisdom of the Far North: Tales and Legends from Chukotka and Alaska; Pipeline to Russia; The Alaska-Siberia Air Route in WWII; and Old Russia in Modern America: Living Traditions of the Russian Old Believers; Ancient Tales of Chukotka, and Ancient Tales of Kamchatka.

Understanding anti-semitism and anti-semites in America

Russian Old Believers in Alaska live lives reflecting bygone centuries

Russian saying: Beat your friends so your enemies fear you

Neo-Marxism and utopian Socialism in America

Old believers preserving faith in the New World

Duke Ellington and the effects of Cold War in Soviet Union on intellectual curiosity

United we stand, divided we fall with race, ethnicity in America

For American schools to succeed, they need this ingredient

Nationalism in America, Alaska, around the world

The case of the ‘delicious salad’

White privilege is a troubling perspective

Beware of activists who manipulate history for their own agenda

Alaska Day remembrance of Russian transfer

American leftism is true picture of true hypocrisy

History does not repeat itself

What is greed? Depends on the generation

Worldwide migration of Old Believers in Alaska