By ALEXANDER DOLITSKY

The household of Russian Old Believers in Alaska in many ways is similar to those of the 18th-and 19th-century Siberian peasants of Russian origin. The Trans-Baykalians build their houses with constructive and decorative elements characteristic of the northern areas of Russia and decorate the interior with red, blue, green, and orange colors, using patterns well-known in Ukraine and Belorussia. The Trans-Baykal area is the only place where architectural elements mentioned in folk descriptions of the homesteads of boyars (grand dukes or Old-Russian noblemen) still survive.

Old Believers in Alaska are not exceptionally tradition-bound in their household construction. Generally, the Old Believers of Nikolaevsk live in large, one-story houses consisting of several rooms, a kitchen, small closets and a veranda. Several small buildings such as banya (steam baths), stoybishche (cattle house), parnik (heated green house) and toilet are within the area of a nuclear family’s household. Each family household constitutes an independent economic unit and is surrounded by a solidly built fence. Furniture in the main house is quite simple, but strong and comfortable.

Although some elements of the traditional architecture and interior design are still present within Old Believer households, modern utilities are favored and extensively used by Old Believers of all religious groupings. An altar with the family icons sitting in a small shelter, curtained with an embroidered covering, stands in a prominent corner of the front room.

Alaskan Old Believers’ economic success can be explained by values that confer normative status on hard work, modest needs, and efficient management of household resources. Old Believers value property and wealth, not as necessities in themselves, but as insurance against possible future hardship. If necessary, Old Believers often assist each other, especially within related nuclear families. Clusters of closely related families are the cornerstones of the community.

The religious and social isolation of Old Believers in Alaska is a major determinant of their quasi-subsistence living conditions. Presently, in contrast to the Amish, Old Believers are not in competition with new technology, i.e., machinery, appliances, electricity, telephones, and other advances. However, Old Believers are economically, mostly agriculturally, self-sufficient. Yet, they are efficient as well. Many conservative families do not purchase food (except sugar, salt and flour) or traditional clothes outside of their community. Each family tries to guarantee its supply of food for the entire year. Their food comes largely from vegetable gardening, fishing, cattle raising, and hunting.

The basic diet is made up of home-grown vegetables, bread and pastries made from wheat and corn, meat that is approved if it comes from an animal with a cloven hoof, fish and shellfish. Among conservative Old Believers in Alaska, animals with paws (e.g., squirrel, rabbit, and bear) are regarded as unfit to eat. None of the Alaskan Old Believers make their living from farming, primarily because of cold and long winters and the short growing season in Alaska.

Trade and exchange play a vital role in Old Believers’ daily life, penetrating the social system and holding the community together. Sometimes Old Believers buy or trade a particular essential item within their community. For example, in the 1980s, Andron Martushev’s family, residents of the Alaskan village of Nikolaevsk, supplied milk to their relatives, Fedor Basargin’s family. Similarly, Fedor’s family sold skillfully tailored traditional garments, made by his wife, Irina, to Andron and other villagers.

Balanced reciprocity is a common form of direct exchange among Old Believers in which goods and services flow two ways. One party gives a gift to another party with an expectation of the return of a gift of equivalent value within a particular period of time. These relationships decrease and eventually disappear among people who are geographically and kinship-wise remote from each other.

Some families specialize in certain subsistence activities such as fishing, carpentry, or shipbuilding. The subsistence specialization reflects the household and structure of the farms. Often nuclear families from the same religious sect cooperate to negotiate a large construction contract from outside the village. The main economic factor of such cooperation, as a rule, is a religious solidarity among relevant Old Believer sects and factions. Normally, Old Believers do not carry out business and trade with opposing Orthodox sects.

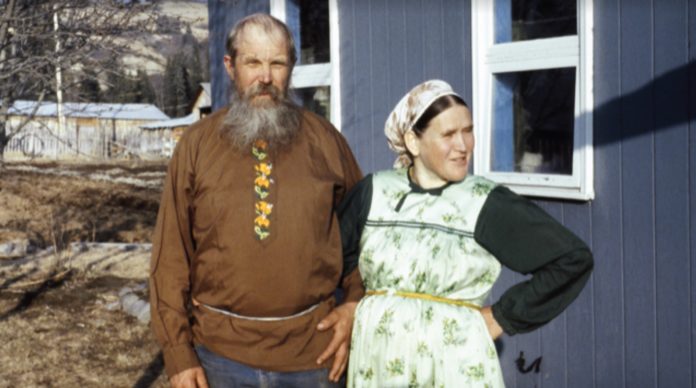

As is the case with nearly every other aspect of Old Believers’ life, the traditions of appearance have religious significance and, historically, are deeply rooted in the medieval past. The physical type and outer appearance of Old Believers is Slavic. The Old Believers of Trans-Baykal, as well as most conservative North American Old Believers, wear clothing reminiscent of the 17th and 18th centuries, despite the stylistic differences of their clothes, reflecting different cultural and geographical origins. Turkish and southern European traditions influenced some styles of Old Believers’ clothing, especially women’s daily dress. At baptism, however, a person is dressed in a shirt bound with a belt and is given a cross to wear around the neck. These three traditional elements — the shirt (rubashka), belt (poyas), and cross (krest)¾must be worn at all times in public. The main apparel items of religious significance are the poyas (woven belt) and the cross around the neck. These two items symbolize the bond between the bearer and Christ. The belt is not taken off except for bathing or sleeping, and the cross is not taken off except in the event of the replacement of a chain.

Men are seen with the long Russian rubashka, a tunic-like shirt girded with a poyas, a woven belt. The women wear a full dress over a long-sleeved blouse and full-length slips. Women lengthen the blouse to form a blouse/slip combination and wear a jumper (sarafan) over it, or talichka along with the ever-present peasant apron.

The sarafan is the traditional dress of the Russian Old Believers in Alaska. It is an all-purpose piece of clothing, serving both as the every-day work dress and as the dress for formal occasions. The sarafan consists of a long skirt and a bodice with shoulder straps. It is worn with a blouse, which provides the sleeves and collar. A belt is always worn around the waist. Often an apron is worn with the sarafan, especially on more formal occasions. Unlike the talichka, the design of the sarafan has not lent itself to many modern revisions.

The talichka is a non-traditional Russian dress, a variation of the sarafan adapted in China. The talichka is never worn in church or prayer hall, and in some conservative communities the policy is not to allow the talichka on any occasion, even for casual wear. Through her choice of wearing a sarafan or talichka, an Old Believer woman makes a statement about her views on the traditional social values of the community she represents.

Children wear the adult-style clothing sized for them. Holiday clothing is more fanciful and colorful, but in the same style.

Men cut their hair, except for a fringe in front, and leave their beards untrimmed. In their religious books, they are enjoined neither to cut their hair at the temples nor to trim the edges of their beards, for to do so would be to deface the likeness of God, in whose image they were created. Old Believers believe that “…a beard is inevitably implied by the notion of man as a reflection of God.”

Women, according to religious rules, are never permitted to cut their hair. They are not allowed to show their arms above the wrists, their legs above the calf, or any other part of their bodies in public. Unmarried women plait their hair in a single braid, and, after marriage, they keep it bound with two braids under a cap (shashmura) covered with a kerchief. The purpose of the shashmura is to hold the hair in place; women’s hair is long — sometimes past their knees. When they wash it, they braid it into two braids and wrap it around their head while it is still wet.

Hence, in the town, on the streets and in residential areas, one is treated to the frequent sight of Russians, resembling peasants of yesteryear, nonchalantly going about their business.

For Old Believers, appearance becomes highly symbolic of one’s attachment to the group and one’s place within society. Traditional dress becomes identified and integrated with a total way of life, and the manner of dressing becomes one of the most important elements of their collective consciousness and representation.

Alexander B. Dolitsky was born and raised in Kiev in the former Soviet Union. He received an M.A. in history from Kiev Pedagogical Institute, Ukraine, in 1976; an M.A. in anthropology and archaeology from Brown University in 1983; and was enroled in the Ph.D. program in Anthropology at Bryn Mawr College from 1983 to 1985, where he was also a lecturer in the Russian Center. In the U.S.S.R., he was a social studies teacher for three years, and an archaeologist for five years for the Ukranian Academy of Sciences. In 1978, he settled in the United States. Dolitsky visited Alaska for the first time in 1981, while conducting field research for graduate school at Brown. He lived first in Sitka in 1985 and then settled in Juneau in 1986. From 1985 to 1987, he was a U.S. Forest Service archaeologist and social scientist. He was an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Russian Studies at the University of Alaska Southeast from 1985 to 1999; Social Studies Instructor at the Alyeska Central School, Alaska Department of Education from 1988 to 2006; and has been the Director of the Alaska-Siberia Research Center (see www.aksrc.homestead.com) from 1990 to present. He has conducted about 30 field studies in various areas of the former Soviet Union (including Siberia), Central Asia, South America, Eastern Europe and the United States (including Alaska). Dolitsky has been a lecturer on the World Discoverer, Spirit of Oceanus, andClipper Odyssey vessels in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. He was the Project Manager for the WWII Alaska-Siberia Lend Lease Memorial, which was erected in Fairbanks in 2006. He has published extensively in the fields of anthropology, history, archaeology, and ethnography. His more recent publications include Fairy Tales and Myths of the Bering Strait Chukchi, Ancient Tales of Kamchatka; Tales and Legends of the Yupik Eskimos of Siberia; Old Russia in Modern America: Russian Old Believers in Alaska; Allies in Wartime: The Alaska-Siberia Airway During WWII; Spirit of the Siberian Tiger: Folktales of the Russian Far East; Living Wisdom of the Far North: Tales and Legends from Chukotka and Alaska; Pipeline to Russia; The Alaska-Siberia Air Route in WWII; and Old Russia in Modern America: Living Traditions of the Russian Old Believers; Ancient Tales of Chukotka, and Ancient Tales of Kamchatka.

A few of Dolitsky’s past MRAK columns:

Read: Russian saying: Beat your friends so your enemies fear you

Read: Neo-Marxism and utopian Socialism in America

Read: Old believers preserving faith in the New World

Read: Duke Ellington and the effects of Cold War in Soviet Union on intellectual curiosity

Read: United we stand, divided we fall with race, ethnicity in America

Read: For American schools to succeed, they need this ingredient

Read: Nationalism in America, Alaska, around the world

Read: The case of the ‘delicious salad’

Read: White privilege is a troubling perspective

Read: Beware of activists who manipulate history for their own agenda

Read: Alaska Day remembrance of Russian transfer

Read: American leftism is true picture of true hypocrisy

Read: History does not repeat itself

Read: The only Ford Mustang in Kiev

Read: What is greed? Depends on the generation

Read: Worldwide migration of Old Believers in Alaska