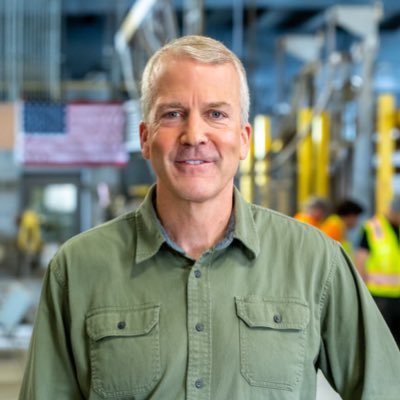

By MICHAEL TAVOLIERO

Alaskans, beware. Be very aware.

The Legislature is maneuvering to dismantle the very protections that have kept our Permanent Fund strong for generations. Their plan? Merge the constitutionally protected principal with the more flexible Earnings Reserve Account (ERA) under the guise of “simplification.”

Robb Myers: Why we should not combine Alaska Permanent Fund accounts

Do not be fooled. This is not simplification. It is surrender to the public unions and other “special interests”, including health care and social service providers, education bureaucracy and school district administrations, municipal governments and associations, nonprofit and advocacy groups, members of our own legislature, itself, and the bureaucratic self-interests of the Alaska Deep State.

By erasing the line between what politicians can touch and what they cannot, lawmakers are stealing from Alaskans to enrich unions, bureaucracies, and special interests that neither create wealth nor advance the future of Alaska, placing our savings, our dividends, and our children’s inheritance on the chopping block.

Alaska Permanent Fund hits record $85 billion, even as Alaskans see smaller dividends

Why the Two-Account Structure Matters

When Alaskans created the Permanent Fund, they built it with two chambers:

- The principal, protected in the Alaska Constitution. Article IX, Section 15 is crystal clear: “At least twenty-five percent of all mineral lease rentals, royalties, royalty sales proceeds, federal mineral revenue sharing payments and bonuses shall be placed in a permanent fund, the principal of which shall be used only for income-producing investments.” This money is locked away for all time.

- The Earnings Reserve Account, which receives investment earnings and can be spent by a simple majority of the Legislature.

This design has worked for decades. It locks the nest egg while still allowing sustainable draws through the Percent of Market Value (POMV) formula about 5 percent each year. The system isn’t broken. But merging the accounts would erase the firebreak. The entire fund would become fair game for short-term budget fixes.

As Sen. Robb Myers warned in his September 3 column in Must Read Alaska: “Combining the accounts is not protecting the fund. It is raiding the fund. It opens the door to overspending in ways Alaskans never voted for.”

What’s at Stake

Every billion dollars siphoned away today is gone forever. That means roughly $50 million in lost earnings every year, for all time. That’s money that could sustain dividends, fund schools, and maintain roads. Instead, it will vanish into the black hole of government overspending.

Already the ERA has been drained in lean years, proving just how fragile it is when lawmakers get desperate. If we merge the accounts, we invite the same pattern, only this time, with no lockbox protecting the core.

Make no mistake: this is how permanent savings die. Not in one dramatic moment, but drip by drip. Withdrawals justified as “temporary.” Promises made that tomorrow will be different. And then, suddenly, the savings are gone.

Lessons from Elsewhere

Other states and nations with resource wealth made these same mistakes. Venezuela, once among the richest oil nations, raided its petroleum revenues to fund short-term political promises. When oil prices crashed, the country collapsed into hyperinflation and poverty with nothing saved.

Closer to home, Alberta created a Heritage Fund like ours, but politicians steadily diverted the money into government budgets. Today, Alberta’s fund sits at only C$17 billion, while Alaska’s Permanent Fund, protected by our Constitution, has grown to over $70 billion.

Even U.S. states have squandered their resource wealth. Louisiana built a severance tax trust fund from its oil and gas boom, but repeated withdrawals drained it to insignificance. Wyoming’s Permanent Wyoming Mineral Trust Fund, while healthier, has been raided multiple times to fill budget gaps.

The lesson is clear: without strict safeguards, savings meant for the future are squandered, and the wealth of a generation is lost forever. These examples spent their savings as quickly as it came in, leaving nothing for the next generation. Alaska was supposed to be different. We had the foresight to set money aside, to create the most successful sovereign savings plan in the world. To tear down that structure now is to betray that vision.

A Better Path Forward

The solution isn’t to merge the accounts. It’s to strengthen the safeguards we already have.

- Keep the two-account system intact. It works, and it has protected Alaskans for decades.

- Constitutionalize the POMV draw. Guarantee that spending remains predictable and limited, without risking the principal.

- Require supermajority votes, or even voter approval, for excess spending. This keeps politicians from raiding the fund during a single bad year.

- Diversify Alaska’s revenue. Oil and gas still matter, but so do coal, critical minerals, fisheries, timber, and renewables. A healthy economy means less pressure to use the Permanent Fund as an ATM.

As Myers put it: “We don’t need to redesign the Permanent Fund to make it work—we need to defend the Permanent Fund from those who want to use it up.”

The Public’s Role

The Legislature works for us, not the other way around. If we let them bulldoze the Permanent Fund’s safeguards, we will lose the foundation of Alaska’s fiscal independence.

It is time to say enough.

Enough with the shell games.

Enough with draining our future to paper over today’s politics and its bureaucratic obesity.

Enough with eroding a legacy that belongs to every Alaskan today and tomorrow.

The Framers of the Permanent Fund saw beyond the next election cycle. They knew oil and gas wouldn’t last forever. They wanted to give Alaskans something that would. That vision has served us well for nearly half a century. To abandon it now would be an act of generational theft.

The choice is ours. Will we rise to defend our inheritance, or sit silent while political elites, devoid of true fiscal discipline, squander it before our eyes?

If we stay quiet, the Legislature will take that silence as consent. If we raise our voices, we can preserve the Permanent Fund as it was meant to be…PERMANENT.

Because once it’s gone, it’s gone. And so is Alaska’s claim to being “king of the hill” in resource stewardship.

Michael Tavoliero: Reversing the catastrophe of NLRB and Wickard decisions

Michael Tavoliero: Open the door to freedom by restoring senior citizens’ choice and dignity

Michael Tavoliero: Coincidences or conspiracies?

Michael Tavoliero: The slow surrender of senior independence to government dependence

Michael Tavoliero: Why HB 57 missed the mark on education reform