A STATE INCOME TAX COULD INCREASE OUTMIGRATION

Alaska, finally emerging from a recession that took place during a national economic boom, has lost population over the past three years, which accounts for some of the state’s stabilizing unemployment rates — many workers have simply left for better opportunities.

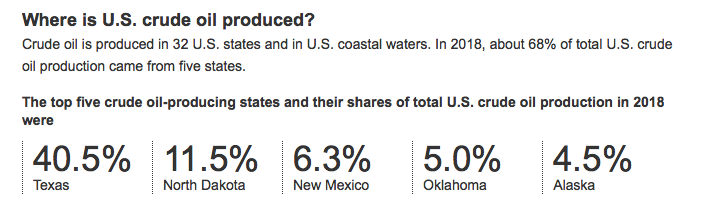

The state also faces a flat or growing state budget, but not enough revenue to serve this ever shrinking population, many of whom are not in the workforce: Oil now accounts for about half of the state’s revenue, state investments’ earnings account for most of the rest.

In 2016, the state population peaked at over 739,649, while today, we’re a state of 731,007.

Between 2018 and 2019, Alaska’s population fell by 3,048, according to the most recent data released by the Alaska Department of Labor.

In Alaska’s largest city, schools reflect the shrinking enrollment: In 2009, the Anchorage School District served 49,492 students, but in 2019 has just 46,794, more than a 5.5 percent drop in a decade. In Juneau, there were 5,237 students enrolled in 2006, but that number is now down to 4,648, an 11 percent drop.

More startling is the crash in kindergarten enrollment: In just five years, the number of kindergarteners coming into the Anchorage School District has dropped 11.5 percent.

Where did everyone go? More than 8,000 people have left the state in the past year, a number that is somewhat offset by newborns. Birth rates are down, however, as evidenced by the shrinking school enrollment, and the population is aging in Alaska: While the group from ages 0-64 declined by 1 percent, the over-65 crowd has grown by nearly 5 percent.

When Alaskans move, they tend to move to jurisdictions without an income tax — Washington, Arizona, Florida, Texas. They also move to Colorado and California, both of which are taxing states; Colorado has a 4 percent across-the-board tax on income, while California has a progressive tax of between 1-12 percent.

INCOME TAXES ON THOSE WHO REMAIN?

How to pay for Alaska state services is the search for the Holy Grail in Alaska politics. Income taxes are being discussed in the caucuses in both the House and Senate as a way to pay for a government that exceeds the revenues now available from oil proceeds and the Permanent Fund Percent of Market Value (POMV). Those are the two current pots of money the bureaucracy feeds on. (The Constitutional Budget Reserve, which is a lending bank to the Legislature, is nearly dry, with just $2 billion available to patch the budget.)

Alaska’s workforce, which would pay taxes under the whispered-about income tax scenario, is shrinking as well.

In November, 348,015 were part of the Alaska workforce, the smallest the state has seen since 2005. The annual wages they bring in are roughly $18 billion a year.

For lawmakers and budget appropriators, these are all significant numbers. Taxing those wages could help fund the services the state is required to provide, and those the state chooses to provide. Fewer workers mean fewer paychecks to tax, and more needy people to serve.

Those who are retiring, if taxed on their retirement income, would be more likely to move to no-tax states.

Even in the Lower 48, where the economy has been on fire over the past three years, populations shift to lower-taxing states.

TAXES DRIVE DEMOGRAPHICS, DECISIONS

Gov. Mike Dunleavy has come out against an income tax, but the Legislature may have other ideas about how to balance the budget.

Must Read Alaska asked former Alaska OMB Director Donna Arduin for help understanding the impact of taxation on population migration between states. Arduin said several Alaskans have reached out to her with the same question, and she pointed to a paper produced by Arthur Laffer, her business partner in Arduin, Laffer and Moore.

Laffer and the American Legislative Exchange Council produce an annual publication, “Rich States, Poor States.” The 10th annual edition lays out the detrimental economic impacts that income taxes have on states’ economies, as they compete with each other for workers and private investment capital.

According to Laffer, income taxes are especially important factors in shaping where people choose to live, work, and invest.

“If A and B are two locations, and if taxes are raised in B and lowered in A, producers and manufacturers will have a greater incentive to move from B to A,” Laffer wrote.

Between 2002 and 2016, more than 20 million people moved from one state to another, often for better economic prospects, Laffer wrote.

“Americans in search of better opportunity often turn to states that are economically attractive. This is a boon for states whose fiscal house is in order and outlook is bright, but a substantial growth deterrent to states whose outlook is already dire,” Laffer wrote. “Generally speaking, taxpayers moved away from states with high personal and corporate income taxes to states with lower or—as is more often the case— no income taxes.”

Alaska is an outlier because it has had no state income tax, little manufacturing, and, in fact, gives each qualified resident a dividend from oil royalties out of the North Slope. That annual incentive may tend to slow the out-migration of those looking for better opportunities.

And yet, according to Laffer, it’s no surprise that all nine states with no personal income tax experienced a net increase from domestic migration during the period studied. States like New York and Illinois languished at the bottom.

The states that lost both the most residents are the usual suspects—New York, Illinois, and California, he wrote. On the other hand, states that have been most successful in attracting residents are Florida, Texas, and Arizona. New York and California have personal income taxes far greater than 5 percent, whereas Texas and Florida do not have an income tax, Laffer noted.

[Read: 11th Annual Edition of Rich States, Poor States]

Launching an income tax in Alaska could increase outmigration, if the experiences of other states are any indication.

The U.S. Census official count of Alaskans begins on Jan. 21 in Toksook Bay. The federal count will also provide data to federal agencies and a lower number of Alaskans will generally mean fewer federal dollars coming back to the state.