BUT WERE TABOO TOPICS DISCUSSED — OR AVOIDED?

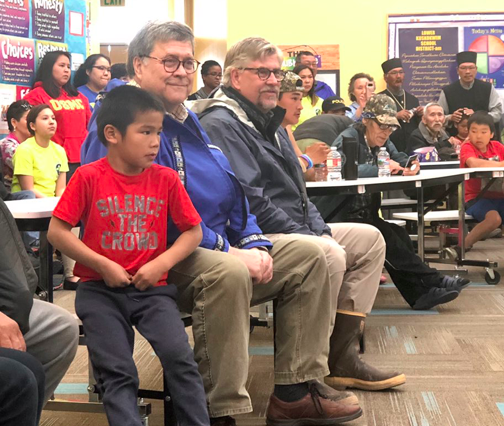

U.S. Attorney General William Barr came to Alaska from Washington, D.C. to learn about violence against Natives.

He participated in a roundtable discussion with Sen. Dan Sullivan at the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium in Anchorage. He travelled to Bethel and Galena. He listened. He observed Native dancers in a community center in Napaskiak.

He is the first U.S. Attorney General to ever visit rural Alaska, the first to visit a women’s shelter in Bethel or travel by boat to a remote village.

He and Sen. Lisa Murkowski listened to the locals talk about the need for more law enforcement in rural Alaska. The need for more resources, more money.

So many questions remain unanswered in the media coverage of the trip. Did the Alaska Native leaders come clean with the full nature of the problem? These are matters that many Alaskans will not speak of openly, for fear of being called racist.

Did they tell Attorney General Barr about this manhunt?

Right now, in an Alaska Native village that must go unnamed, troopers are looking for an extremely dangerous man. The man is Native and he is on the loose. The Troopers asked the village council to help them locate the man. The council refused to help. They are protecting him and hiding him from Troopers. The man is a known vicious sexual offender and Troopers have now stepped up the manhunt, first devoting three, and now five officers searching for this man, in a matter that could be and should be already handled. Across village Alaska, Native leaders often do not cooperate with law enforcement, and just as often are known to protect criminals.

Did they tell Attorney General Barr about this recent case?

In a village that must go unnamed, a Village Public Safety Officer arrested a tribal elder recently. It was a rightful arrest. But the village council didn’t agree with the arrest, so they wrote a letter to the hiring authority (tribal agency that must go unnamed) saying they don’t want that VPSO to serve their community, and the VPSO was removed from that position. The tribal entity hired a different person as a VPSO, sending a message that the new VPSO can only make arrests the community leaders agree with.

It’s not an isolated problem. VPSOs know that their jobs are very political, and that they can lose their position in a heartbeat if they arrest a powerful person.

NATIVE VILLAGE VIOLENCE — STUDIED TO DEATH

Study after study show that Alaska Native women are assaulted in staggering numbers.

A Department of Justice study reveals that 84 percent of Alaskan Native women have experienced violence, 56 percent have experienced sexual violence. Roughly 50 percent of the women said they had experienced physical violence. Over 60 percent had experienced psychological aggression. 49 percent had been stalked.

It’s not just the women. 27 percent of Alaska Native men have experienced sexual violence, 43 percent have experienced physical violence by an intimate partner, and 73 percent have experienced psychological aggression by an intimate partner.

The 2016 study, by UAA’s Dr. Andre Rosay, says that 92.6 percent of the Native women and 74.3 percent of the Native men had talked to someone about what the perpetrators did to them. In other words, most victims are not remaining silent. And yet, the problem continues unabated and perpetrators are not held accountable.

Then there’s this: Fifty-four percent of Alaska’s sexual assault victims are Alaska Native, even though Alaska Native people comprise not quite 15 percent of the population.

THE PERPS

Who are the perpetrators of this violence? That’s harder to define, but in rural Alaska villages, where Natives are predominant, it’s a stretch to say that perpetrators are a race other than the residents who live there.

Yet, we are told by the report that 96 percent of victims say perpetrators were from another race. Something doesn’t add up.

An important data point: A review of Alaska’s Sexual Offender Database shows that Alaska Native men dominate the sex offender and kidnapper registry.

CHOOSE RESPECT, LOCK ‘EM UP

Some say the solution rests with the tribes.

With 229 federally recognized tribes in Alaska — far more “tribes” than there are incorporated communities — beefing up law enforcement, allowing villages to enforce tribal laws and allot justice to non-tribal members — these are some of the solutions offered that have all kinds of problems attached to them. The largest Native community, after all, is in Anchorage, and it’s multi-tribal.

Did Attorney General Barr get the full picture while he was in Alaska? Did tribes and village leaders come clean about the problem of Native-on-Native violence, the protection of perpetrators by village leaders, or the fact that some communities are — to be blunt — not much more than rape camps?

Likely, Barr heard for the need for more money, better jails, more shelters for victims, and social services. He likely did not hear about the need for personal, family, and community responsibility for communities that want, more than anything, sovereignty. They want money to run affairs their way.

If rural Alaska wants to end the epidemic of violence, it will mean locking up or removing more of their men. This is complicated business, because these offenders can be sent to prison, can be removed from households and communities where they’ve harmed people, but at great cost, because communities without men are going to be very different communities. Boys growing up with fathers who are in prison have very different challenges.

Barr vowed to provide greater security to rural Alaska. What that means is locking up perpetrators. And what that means is arresting and prosecuting them. Are village leaders ready for that?

Do you know of a story from rural Alaska where village leaders did not allow law enforcement to arrest a perpetrator? Add it in the comment section below.