By ALASKALINE NEWSLETTER

Editor’s note: Must Read Alaska is noting here a unique weather event that almost took down a commercial flight leaving Juneau 30 years ago on Jan. 29, 1993. But for the quick thinking of the pilot, dozens of lives would have been lost in a horizontal tornado that occurred upon takeoff and nearly flipped the aircraft. This story first appeared in the Alaska Airlines employee newsletter in 1994. The incident and the solution arrived at ‘on the fly’ became instrumental to training pilots about what to do in such a circumstance).

In 20 years as a pilot, Captain James “Jake” Jacobsen had racked up more than 15,000 hours of flight time, but when he looked back over his career, his most vivid memory was of 15 seconds over Juneau on the night of January 29, 1993.

He and First Officer Kevin Nelsen were later honored with the Air Line Pilots Association Superior Airmanship Award for their flying skills that night.

The incident began about 6:30 pm. The sky was dark. A light rain was falling. Winds were from 120 degrees at 30 knots — not the best flyng conditions by any means, but not unusual for Southeast Alaska either.

Two previous jet departures reported moderate turbulence on the climb out.

Jacobsen and Nelson took off toward the east on a flight to Seattle with two pallets of freight and 31 passengers. Flight attendants Kim Wien (Merrill Wien’s daughter) and Barb Cooley were securely strapped in their jumpseats.

Low mountains around the airport required the B737-200 to make a 180-degree right turn shortly after takeoff. About halfway through the turn the right wing of the jet suddenly dipped down toward the ground.

“We rolled over in excess of 60 degrees and I could not get the left wing back down,” recalled Jacobsen. The aircraft started losing altitude and air speed. It was in danger of stalling.

The aircraft had been hit by a dangerous “rotor shear,” a type of wind shear often described as a horizontal tornado. It is caused by one air mass moving over the top of another, sometimes at speeds of 100 knots or more.

“When you are flying an aircraft you need three things — altitude, air speed, and ideas,” said Jacobsen. “We were rapidly running out of the first two and didn’t have a lot of time to come up with the third.”

As the aircraft hung almost motionless in the air, luggage became weightless. Coats, purses, and books tumbled out from under the passenger seats and flew around the cabin.

“It looked like the inside of a popcorn machine,” said Wien.

A pocket radio in the first row rocketed the entire length of the cabin and hit the aft bulkhead.

“It had been windy in Southeast Alaska that day, so we were extra careful about stowing hand-carried items before takeoff,” said Wien. “Everything was really buttoned up, but there is no way to keep everything tied down in a situation like that.”

Jacobsen credited his experience as a light plane pilot, the superior flight characteristics of the B737-200, and luck with saving him and his passengers that night.

ALPA Executive Vice President and Alaska Airlines Captain Joe Salz believed Jacobsen’s many years of flying out of Juneau was also a factor.

“Jake is one pilot who really knows Juneau,” said Salz. “He has spent years flying in and out of Juneau in all kinds of aircraft.”

In fact, Jacobsen and his family owned Wings of Alaska, a small charter and scheduled airline based in Juneau.

Nelsen also had an extensive background in Alaska flying. Born and raised in Seward, he had more than 12,000 hours of flight time, including 5,000 hours flying floatplanes throughout the state.

Before the aircraft rolled over, Jacobsen jammed the throttles to full power and then kicked in full right rudder and dove the aircraft toward the ground to gain air speed.

At what he estimates was less than 200 feet above the ground, Jacobsen was able to pull out of the dive. His first attempt to climb failed. The second try was successful, but as the aircraft struggled to gain altitude it was again hit by the same wind shear.

“We were able to keep the wings level this time because we weren’t turning,” said Jacobsen. Eventually, the aircraft was able to gain altitude, bringing the emergency to an end.

Through it all, Nelsen called the instrument readings off out loud for Jacobsen, who was busy trying to gain control of the aircraft. Extreme turbulence cause the needles to bounce around so much that Nelsen had difficulty accurately reading the airspeed and altitude indication.

The passengers were remarkably quiet throughout the emergency. Wien remembered no screaming, crying, or hysterics. Later, a passenger commented, “I knew we were in trouble when I saw the lights of the Fred Meyer store out of the top of the window.”

Wien said, “There was no sugar coating it. Everyone knew how close we came.”

Despite their brush with disaster, Jacobsen and Nelsen decided to go on to Seattle. They had no choice. “The engines were not damaged. Sitka was closed because of high wings, it was blowing about 75 knots at Ketchikan, and we didn’t want to go back to Juneau for obvious reasons, ” said Jacobsen. In fact, Nelsen flew the departure while Jacobsen called the tower to recommend that the Juneau airport be closed — and it was.

Looking back on it, Jacobsen said, there was no way he and Nelsen could have predicted the wind shear.

“The winds on the surface weren’t that bad. I’ve taken off from Juneau with it blowing much harder,” Jacobsen said.

As soon as the aircraft was safely out of danger, Jacobsen made a PA announcement, then he went back into the cabin to talk to the flight attendants and reassure the passengers.

“That was excellent on Jake’s part, to go back and talk face-to-face with the passengers,” said Nelsen.

Though shaken, Cooley and Wien pulled themselves together and started the meal service.

“Maybe I was in shock, but my first thought was, ‘OK, that was a wild ride, but I’ve got to get these meals out,” said Wien. “Our knees were shaking but we went through our routine. That helped because it gave us something to focus on. We offered everyone complimentary drinks, but surprisingly, only one or two people took us up on it. I think it was a very sobering experience for everybody.”

Jacobsen lauded the performance of the two flight attendants. Holding back their own emotions, “Barb and Kim did an excellent job serving the passengers,” he said. “They were very professional. They performed a very exemplary service.”

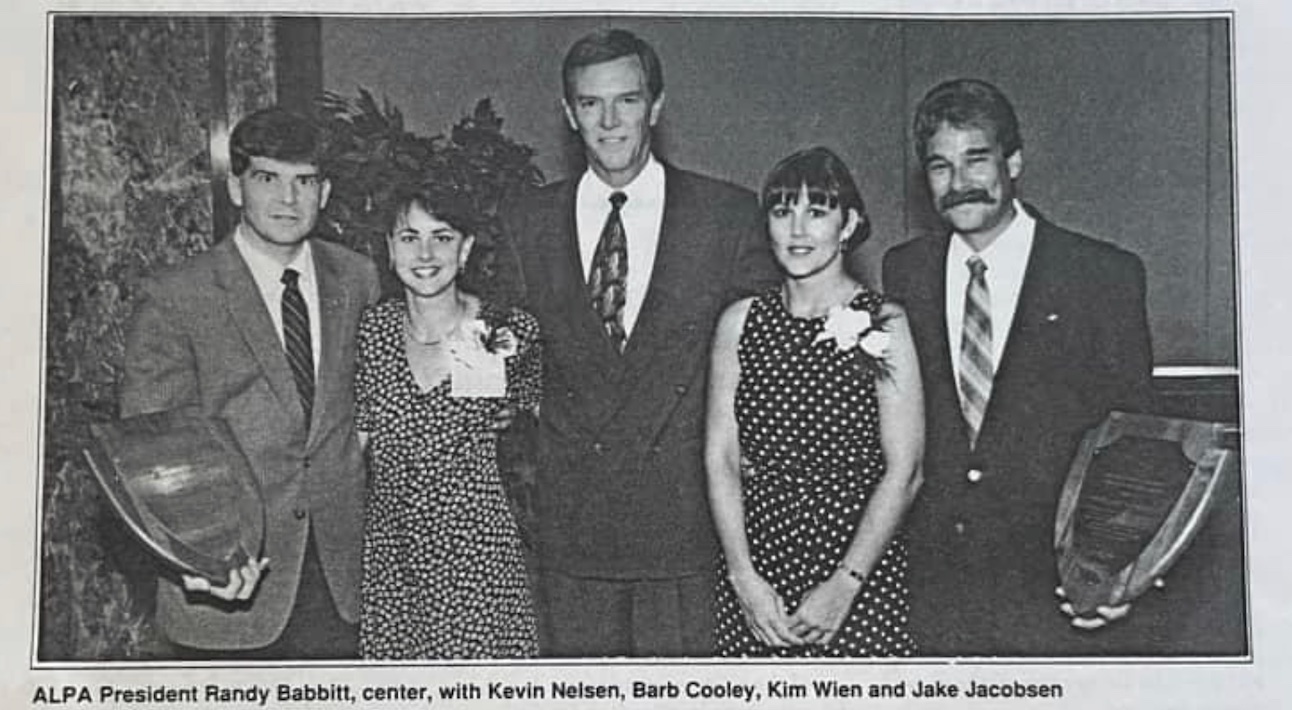

In recognition of their performance that night, Jacobsen and Nelsen receive the 1993 Superior Airmanship Award from ALPA. The award is described as ALPA’s equivalent of the military’s Distinguished Flying Cross.

The plaque they received read, “For demonstrating great skill and professionalism on January 29, 1993, when you successfully maneuvered your B737 aircraft through severe meteorological conditions after departure from Juneau, Alaska Airport.”

The award was presented in Washington, D.C. by ALPA President Randy Babbitt. FAA Administrator David Hinson was the event keynote speaker. In the audience were members of the crew’s families and more than a dozen Alaska Airlines pilots, including the entire ALPA Safety Committee and several ICE instructors. Jacobsen’s mother flew from Juneau to see her son receive the award.

Cooley and Wien stood on the stage with Jacobsen and Nelsen as they received their award.

“We stuck together as a crew through it all,” said Jacobsen.

First published by Alaska Airlines’ AlaskaLine newsletter, Oct. 7, 1994.