By DAVID MCMAHAN

In 1867, after more than a century of occupation, Russia sold her Alaska holdings to the United States. The transfer ceremony took place on the afternoon of Oct. 18 of that year on Sitka’s Castle Hill.

Around 250 U.S. troops in blue uniforms stood in formation on one side of the flagpole while the red-uniformed Russian brigade took position on the opposite side. The ceremony was punctuated by booming cannon salutes from the nine-inch cannons of the USS Ossipee, followed by those of the Russian shore battery.

Brigadier General Rousseau represented the U.S. while Captain Peschurov represented the Tsar of Russia Alexander II.

According to popular accounts, the tenacious Russian flag became entangled and was only removed after several attempts so that the American flag could be raised.

Despite recent claims by many Russian officials that Alaska was only “leased” by the U.S. government from Russia for 100 years, the historical records of the purchase are undeniable. Events leading up to the sale were influenced by the social, political, and economic undercurrents of the time.

Russia’s exploration of North Pacific, including Alaska, began with voyages in 1648, 1728, 1732, and 1741. Reports of furs brought about the formation of a number of small companies to capitalize off the newly found riches. In 1799, Russia’s first joint stock company, the Russian-American Company, was created under imperial charter.

The company, whose shareholders included Russian monarchy and nobility, monopolized the Alaska fur trade for 68 years. During that time, a maximum of about 820 Russians were ever present on Alaska soil at the same time; mostly in the southern coast of Alaska, stretching from Unalaska to Sitka. The bulk of the workforce was comprised of Natives and Creoles of Alaska.

The mid-19th century in Russia was an age of economic reforms that abolished serfdom in 1861 and embraced Laissez-faire attitudes (i.e., fewer regulations). Encouraged by the Russian press, there was a widespread belief that Alaska Natives were being mistreated through forced labor.

There were also accusations that the company violated the civil rights of Russian workers by prohibiting their importation of alcoholic beverages and sell of weapons to Natives.

The company’s charter was set to expire in 1862, and the controversy complicated negotiations for a new charter. Consequently, the company was forced to operate under extensions. Russia began to consider giving up her interests in Alaska during the 1850s, and in 1860 sent inspectors to Sitka to review (assess) company affairs and to appraise its assets to about $11.5 million in U.S. dollars. Their report suggested that the company was economically sound.

Politically, however, Russia’s ability to sustain its Alaska operations was bleak. The Crimean War (1853–1856) against Turkey and its allies Great Britain and France had hurt Russia financially and politically, and the prospect of subsidizing Alaska operations was not appealing. Tsar Alexander II and his advisors knew that Russia could not defend its remote oversea Alaska holdings against seizure by the British if war broke out again.

While Russia’s relationship with Great Britain was tense, the U.S. was a potential ally. The U.S. had provided humanitarian support to Russia during the Crimean War (1853-56), and Russia (unlike Great Britain and France) was sympathetic to the Union during the U.S. Civil War of 1861–1865. It has even been argued that the threat of Russian intervention kept Great Britain and France from providing military support to the Confederacy.

Despite a friendly and cordial relationship, Russia knew that U.S. public opinion favored a “Manifest Destiny” for expansion throughout the North American continent. It was better to transfer Alaska to the U.S. under mutually agreeable terms than to try to defend it against seizure by Great Britain or encroachment by American traders and whalers.

In the end, Russia’s decision to sell Alaska came much easier than U.S. congressional approval to buy, which was clouded by controversy and allegations of bribery.

It should also be mentioned that, from the perspective of Alaska Natives, Russia could not sell what she did not own.

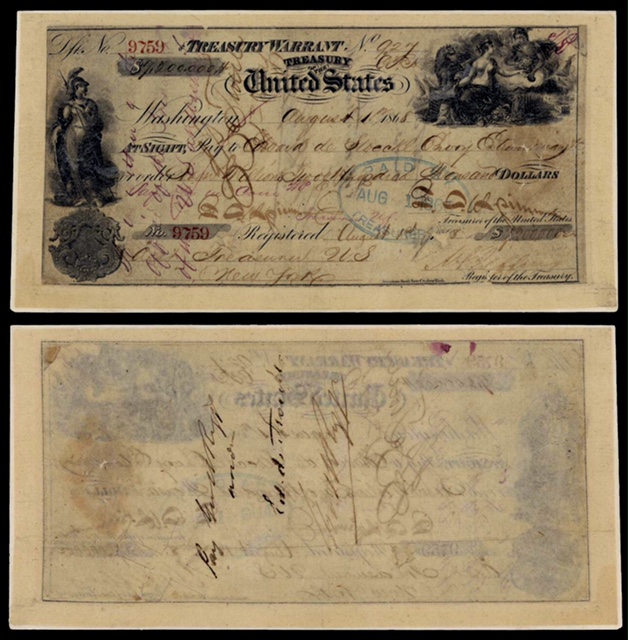

The ‘Alaska Treaty’ was signed on March 30, 1867, with a purchase price $7.2 million. Article 1 ceded “all the territory and dominion now possessed by his said Majesty on the continent of America and in adjacent islands.” Other articles addressed the status of Russian residents residing in Alaska, the disposition of private individual property, the disposition of Orthodox churches, and the details of compensation. U.S. Secretary of State, William Henry Seward, championed the opportunity to purchase Alaska.

The U.S. Senate overwhelmingly ratified (approved) the purchase on April 9, 1867, it passed the House on July 14, 1868, and, finally, became a law on July 27, 1868.

Opponents of the purchase in the press began using the term “Seward’s Folly” or “Seward’s Icebox” to describe Alaska. Some stories have attributed the $0.2 portion of the payment as compensation for the “Alaska Ice Trade”, while others have attributed it to bribes for Russian officials.

Still another story alleged that Russia’s payment, in gold bullion, was lost when the transport ship to Russia wrecked.

In the absence of primary records, these myths must for now be attributed to an unscrupulous press. Russia’s North American legacy has survived through elements of the Russian Orthodox religion, language, and cultural traditions in many Native communities of Alaska today.

Until retirement from the State of Alaska in May 2013, David McMahan served as Alaska’s State Archaeologist and a Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer. He is a board member of the Alaska-Siberian Research Center. With BA and MA degrees in anthropology from the University of Tennessee and more than 30 years in professional archaeology, his interests and skills are diverse; he has multiple training and certifications including forensic anthropology and as an adviser to the State Medical Examiner, he helped solve some of Alaska’s most gruesome crimes.

Alexander Dolitsky is a regular writer for Must Read Alaska. He edited this submission.