By DAVID MCMAHAN

In 1867, after more than a century of occupation, Russia sold her Alaska holdings to the United States. The transfer ceremony took place on the afternoon of Oct. 18 of that year on Sitka’s Castle Hill.

Around 250 U.S. troops in blue uniforms stood in formation on one side of the flagpole while the red-uniformed Russian brigade took position on the opposite side. The ceremony was punctuated by booming cannon salutes from the nine-inch cannons of the USS Ossipee, followed by those of the Russian shore battery.

Brigadier General Rousseau represented the U.S. while Captain Peschurov represented the Tsar of Russia Alexander II.

According to popular accounts, the tenacious Russian flag became entangled and was only removed after several attempts so that the American flag could be raised.

Despite recent claims by many Russian officials that Alaska was only “leased” by the U.S. government from Russia for 100 years, the historical records of the purchase are undeniable. Events leading up to the sale were influenced by the social, political, and economic undercurrents of the time.

Russia’s exploration of North Pacific, including Alaska, began with voyages in 1648, 1728, 1732, and 1741. Reports of furs brought about the formation of a number of small companies to capitalize off the newly found riches. In 1799, Russia’s first joint stock company, the Russian-American Company, was created under imperial charter.

The company, whose shareholders included Russian monarchy and nobility, monopolized the Alaska fur trade for 68 years. During that time, a maximum of about 820 Russians were ever present on Alaska soil at the same time; mostly in the southern coast of Alaska, stretching from Unalaska to Sitka. The bulk of the workforce was comprised of Natives and Creoles of Alaska.

The mid-19th century in Russia was an age of economic reforms that abolished serfdom in 1861 and embraced Laissez-faire attitudes (i.e., fewer regulations). Encouraged by the Russian press, there was a widespread belief that Alaska Natives were being mistreated through forced labor.

There were also accusations that the company violated the civil rights of Russian workers by prohibiting their importation of alcoholic beverages and sell of weapons to Natives.

The company’s charter was set to expire in 1862, and the controversy complicated negotiations for a new charter. Consequently, the company was forced to operate under extensions. Russia began to consider giving up her interests in Alaska during the 1850s, and in 1860 sent inspectors to Sitka to review (assess) company affairs and to appraise its assets to about $11.5 million in U.S. dollars. Their report suggested that the company was economically sound.

Politically, however, Russia’s ability to sustain its Alaska operations was bleak. The Crimean War (1853–1856) against Turkey and its allies Great Britain and France had hurt Russia financially and politically, and the prospect of subsidizing Alaska operations was not appealing. Tsar Alexander II and his advisors knew that Russia could not defend its remote oversea Alaska holdings against seizure by the British if war broke out again.

While Russia’s relationship with Great Britain was tense, the U.S. was a potential ally. The U.S. had provided humanitarian support to Russia during the Crimean War (1853-56), and Russia (unlike Great Britain and France) was sympathetic to the Union during the U.S. Civil War of 1861–1865. It has even been argued that the threat of Russian intervention kept Great Britain and France from providing military support to the Confederacy.

Despite a friendly and cordial relationship, Russia knew that U.S. public opinion favored a “Manifest Destiny” for expansion throughout the North American continent. It was better to transfer Alaska to the U.S. under mutually agreeable terms than to try to defend it against seizure by Great Britain or encroachment by American traders and whalers.

In the end, Russia’s decision to sell Alaska came much easier than U.S. congressional approval to buy, which was clouded by controversy and allegations of bribery.

It should also be mentioned that, from the perspective of Alaska Natives, Russia could not sell what she did not own.

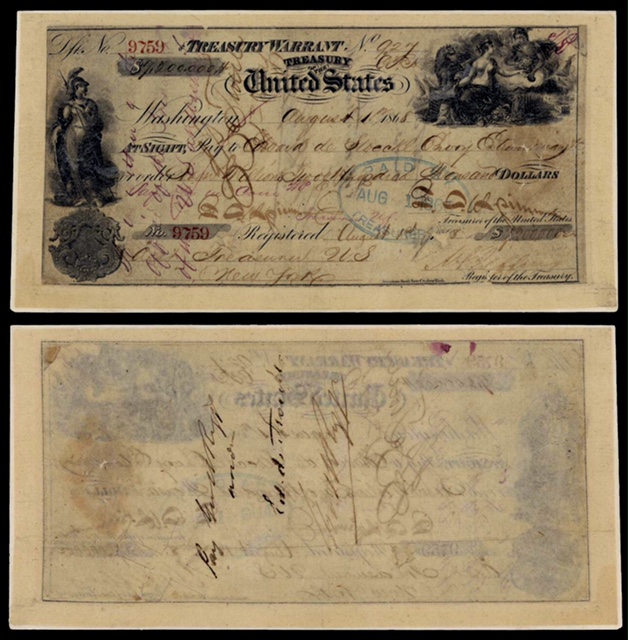

The ‘Alaska Treaty’ was signed on March 30, 1867, with a purchase price $7.2 million. Article 1 ceded “all the territory and dominion now possessed by his said Majesty on the continent of America and in adjacent islands.” Other articles addressed the status of Russian residents residing in Alaska, the disposition of private individual property, the disposition of Orthodox churches, and the details of compensation. U.S. Secretary of State, William Henry Seward, championed the opportunity to purchase Alaska.

The U.S. Senate overwhelmingly ratified (approved) the purchase on April 9, 1867, it passed the House on July 14, 1868, and, finally, became a law on July 27, 1868.

Opponents of the purchase in the press began using the term “Seward’s Folly” or “Seward’s Icebox” to describe Alaska. Some stories have attributed the $0.2 portion of the payment as compensation for the “Alaska Ice Trade”, while others have attributed it to bribes for Russian officials.

Still another story alleged that Russia’s payment, in gold bullion, was lost when the transport ship to Russia wrecked.

In the absence of primary records, these myths must for now be attributed to an unscrupulous press. Russia’s North American legacy has survived through elements of the Russian Orthodox religion, language, and cultural traditions in many Native communities of Alaska today.

Until retirement from the State of Alaska in May 2013, David McMahan served as Alaska’s State Archaeologist and a Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer. He is a board member of the Alaska-Siberian Research Center. With BA and MA degrees in anthropology from the University of Tennessee and more than 30 years in professional archaeology, his interests and skills are diverse; he has multiple training and certifications including forensic anthropology and as an adviser to the State Medical Examiner, he helped solve some of Alaska’s most gruesome crimes.

Alexander Dolitsky is a regular writer for Must Read Alaska. He edited this submission.

I for one am Thankful Russia transferred its rights over to America else I’d grown up a communist!

There is a story that caught my many years ago regarding the sale of Alaska to the US from Russia.

I wish I could recall exactly where I read a article that claimed that Abraham Lincoln negotiated with the Czar of Russia at the time to sail his fleet of warships into East Coast ports at some point during the US Civil War. The show of power was to discourage any interference from the British in the American Civil War.

The purchase of Alaska was a cover for the US to pay the bill that was owned to Russia for their efforts.

It is interesting to note that William Seward was the Secretary of State under Lincoln and Andrew Johnson.

Urban Legend?

“It should also be mentioned that, from the perspective of Alaska Natives, Russia could not sell what she did not own.”

–

“Direct annexation, the acquisition of territory by way of force, was historically recognised as a lawful method for acquiring sovereignty over newly acquired territory before the mid-1700s. By the end of the Napoleonic period, however, invasion and annexation ceased to be recognized by international law and were no longer accepted as a means of territorial acquisition.”

“The title of discovery, would, under the most favourable and most extensive interpretation, exist only as an inchoate title,”

Turning to relatively recent cases, in the Anglo-Norwegian Fisheries case of 1951, the UK agent argued that governments protest “in order to make it quite clear that they have not acquiesced and to prevent a prescriptive case being built up against them.”

“…belated protest had no significance under international law, and that the protracted absence of protest now precludes China from claiming sovereignty, based on the principle of estoppel.”

Settlement of Alaska’s Native land claims were based in part by the Natives having long voiced their relationship to the land, which superseded any claims of Russia’s having delivered title to Alaska to the US. That continued protest prevented Russia and America from building a prescriptive case against Alaska Natives claim to ownership.

Russia claiming discovery, and annexation did not confer title under international law existing at the time of the purchase. All America bought was quiet title.

America had only inchoate title until the ANCSA was finalized.

Why did the US resort to using ANCSA to extinguish Aboriginal land title in Alaska? Because, under existing international law, Alaska’s Natives still had clear title. Of course so much water had flowed under the bridge that nobody was going to get evicted … which brought about the only compromise which made sense.

By the 1860s, coastal Alaska was more an American colony than a Russian colony and the British were pressing in from Canada. The Russians were hardly able to provide provender to the Alaska colony and trade relations between Russian and China, the primary market for otter fur, were so bad that the Russians were only allowed to trade at an entrepot, the name of which escapes me, far up the Amur River. The Americans on the other hand had a bustling and very profitable trade exchanging sundries, arms, and alcohol with the Natives and provender with the Russians for the valuable otter fur. America enjoyed good trade relations with China and could trade in any major port. It was largely a New England based trade of otter fur for Chinese tea, texiles, and porcelain. Voyages often took four years and involved a circumnavigation of the World, but the profits averaged 4000%. The Russian “sale” of Alaska to the US was really just making a virtue of necessity.

In June and July the Confederate commerce raider CSS Shenandoah arrived in Alaskan Arctic waters seeking the US whaling fleet and other US shipping. Shenandoah met the US whaling fleet off what is now Kotzebue and destroyed most of it, leaving only enough shipping to return the survivors to US territory. Shenandoah then set sail for San Francisco with the intention of shelling it. Along the way she met a British mail packet and learned that she now really was the pirate ship the US accused her of being since the Confederate States no longer existed. Shenandoah sealed her gun ports, stowed her guns, and set sail around the Horn and through the Atlantic for Liverpool, and made it with the US and British navies looking for her. She docked in Liverpool, asked for the US Consul, and surrendered her colors to him, and thus ended the US Civil War in November of ’65.

The US made claims against Great Britain for the damage done to US shipping by British ships sold to the CSA. Commercial and diplomatic arbitration was all the rage in the last half of the 19th Century and the case went to arbitration styled as “The Alabama Claims,” for the most famous of the Confederate raiders. The arbitral panel found for the US, and IIRC, awarded $17 Million to the US, $6.8 Million of which was for the damage done by CSS Shenandoah off Kotzebue. So, net, after the Alabama Claims award, the US paid $400 thousand dollars for Alaska.

Note: I accidentally omitted that China was trying to lay claim to an island which they had abandoned claim to for over a hundred years. Their late claim was was denied by estoppel.

Thank you Suzanne for another good article! I wish to add to the article and comments above with another observation. There was at least a two decade long complaint coming from Russian officials to our U.S. State Dept. prior to the “sale” of Alaska to the U.S. Yankee whalers were trading directly with Alaska Natives for furs in violation of an agreement between the two countries. However as Art Chance points out, the Russians were locked out of the Hong-Kong fur market after the Crimea conflict and had to rely upon those cheating” yankee’s” for their supplies and income. An untenable position to be in, if you were a Russian.

Secondly, I would submit that the threat of a British takeover of Alaska while feared by many may have been unfounded. The Hudson Bay Company actually established an out post right under the Russians nose in a place called ” Fort Durum”, (today known as Taku Harbor). Fort Durum was a financial disaster for the Brit’s. The brit’s packed up and went home prior to the “sale” of Alaska to the U.S. From what I can tell from my study, Alaska was purchased only because William Seward was an Anglophobe of the first order. It has been said that Seward tried provoking England into a war with the Union even during the contest with the Southern States. Lincoln reportedly told Seward, “you may start a war with England Mr. Seward, but only after I have defeated Robert E. Lee, one war at a time Mr. Seward, please.”.

Interestingly, some believe that the assassination of President Lincoln and the attempted assassination of Mr. Seward were funded and planned by the Bank of England…

Do you truly own something that you cannot keep and protect? The czar sold off it’s holdings in Alaska to pay for bills incurred during previous wars. Thank God manifest destiny was a thing back then. Reflect on what the world would be like if it hadn’t taken place. It was too great of a territory to defend with Stone age tools.

Is there any truth to the rumor that Russia never sold Alaska, per se, to the United States, but only all Russian Orthodox church property, Russian fur trading posts and Russian settlements in Alaska?

In his history of the Taku River fort and adjacent territory UAS history professor emeritus Wally Olson, now deceased, estimates that prior to the British trading post there and the Russian hold on Sitka fully sixty percent of the population of southeast consisted of slaves. Some writers maintain that local Natives kept slaves in southeast through the end of the 19th century. Anyone can speculate what would have happened to the greater part of what is now our state had the Russians not sold Alaska. The Japanese trounced Russia twice after the sale and obtained claims to land formerly claimed by Russia in each of the two peace settlements, so Alaska might have become part of the Empire of Japan. Great Britain might have claimed southeast, and any boundary between Canada and whatever Alaska became would have likely been west of the current boundary. If Russia had still owned Alaska in 1917 then North Pacific history could have been very different. If Japan had obtained Alaska after either of those wars then possibly WWII would have been fought differently. By the way, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 extinguished all aboriginal claims, and looking at how Russia and Japan treat aboriginal people even today strongly suggests that the Alaska Purchase was a very lucky day for the various nomadic groups, tribes and mixed blood Russians back in 1867.

KAYAK: That’s a fair take on what was, and could have become.

SCHENKER: As you point out, there was a lot more to the purchase than what’s in our text books.

Robert Schenker,

Contest with Southern States? interest term for a civil war.

When Russian interests were transferred many Aleuts chose to repatriate to Russia. There is a larger population of Aleuts in Russian than there are in Alaska after decimations on the Alaskan Peninsula who have deep cultural historic base of knowledge which they share culturally. Also, Russia has Asian populations that integrated easily with Alaskan populations in the Russian occupation. Extensive DNA studies show Aleuts are racially separate from other Alaskan tribes who get dissimilar illnesses etc. Alaskan governments are completely uninterested in the people of the land in any way. The results of decisions made are often random and unwise.

A civil war denotes a conflict in which one side is trying to take over the government. The South was not trying to take over the Federal Government–they were trying to secede from it. Maybe just semantics but explains why most southerners use other terms for that situation.

Harbor Guy, would you feel more comfortable with ” the war of Yankee Aggression”? Just wondering. There are many terms to describe a conflict, contest is but one.

Gretchen, you are correct the South did not have plans to ” take over” the Northern States, however they did fire the first shot.

@Robert A. Schenker – There are different ways to look at that “first shot.” The Provisional Government of the Confederate States and the State of South Carolina had asserted to the US that Ft. Sumpter was now a part of the Confederate States and the CS was willing to compensate the US for its improvements to the land, Ft. Sumpter. SC and the CS demanded US evacuation of Ft. Sumpter. Instead, Lincoln have a keen sense of the temprament of his adversary goaded the Confederates by instead re-supplying the fort and the firebrands did what firebrands do. If there had been some cooler heads in Charleston that evening, history might have been written differently.

Art Chance, Interesting that you mention South Carolina and Hot Headed Firebrands in the same sentence. Reviewing the debates concerning the forming of our glorious Constitution recorded by James Madison on the question of Slavery… it looked for awhile as if the Framers were willing to seriously deal with the issue, until, the South Carolina contingent kicked up a fuss and muddied the water. In the end a sunsetting of Slave Importation was all that was achieved. So, perhaps Lincoln knew his adversary pretty well and did bait the trap as it were.

I’m learning more American and Alaskan history here than I ever did in school.

Comments are closed.