TRIBAL AFFAIRS COMMITTEE DRESSES DOWN COMMISSIONER PRICE

At the invitation of the newly created House Special Committee on Tribal Affairs, Public Safety Commissioner Amanda Price was giving data to the committee about rural public safety in Western Alaska. Lots of data.

But from the outset, the hostile reception she received from committee Chairwoman Rep. Tiffany Zulkosky and House Speaker Bryce Edgmon came through loud and clear.

Price is somewhat of a data machine. She delivers numbers like an high-powered rifle — fact after fact after fact. And although passionate about public safety, she is a linear presenter who is tasked with giving appropriators the information they need to make decisions.

Right now those decisions involve whether to cut back the funding for the Village Public Safety Officer program, as Gov. Dunleavy has proposed doing. Most observers feel the program is challenged, if not broken.

Price didn’t know she was walking into a trap, one apparently set by Zulkosky and Edgmon, the latter of whom has let it be known throughout the Capitol that he doesn’t like this particular Public Safety commissioner. The two were loaded for bear.

Price began her presentation on the rural Alaska public safety components. Recruitment, hiring, retention — it’s all an historic challenge for the Village Public Safety Officer program in rural Alaska. The program works through grantees, which are tribal associations that provide the public safety services with state grants. They are not contractors, she noted, but grant recipients, a difference she felt was an important distinction.

But in spite of her skills as a presenter and her command of the facts, she was interrupted repeatedly by Zulkosky and Edgmon, who is vice chair of the committee.

Zulkosky had asked members to hold their questions until the end of the presentation. But the House Speaker couldn’t wait and she gave him a pass. Edgmon started asking Price questions that were posed in the form of accusations — why is the State of Alaska getting in the way of the VPSO program? Why does the department feel it needs to exert such control? Why can’t the tribal associations — the grantees who manage the VPSO program — have their hands untied by the bureaucracy?

Between Zulkosky and Edgmon, there were a dozen of these pointy-edged questions that seemed to come from a pent-up anger.

Why were some VPSO grant applications denied in 2017 and 2018? The two wanted her to give detailed history of what had happened before she became commissioner.

Finally, with his voice shaking, Edgmon said he had viewed the video of her in another committee, and he accused her of saying that the VPSO program is more expensive than the State Trooper program, because Price included indirect costs for the VPSO program but did not for the Trooper program.

He then accused Price of having “an indifference” to the VPSO program and wanted her to explain why she said it was more costly.

[Watch the entire proceedings at this link]

“Rep. Edgmon … Mr. Chairman … Thank you for the question. No, sir, I don’t believe I said that a VPSO is more expensive than an Alaska State Trooper. I believe that I said that they’re a bit comparable in cost…”

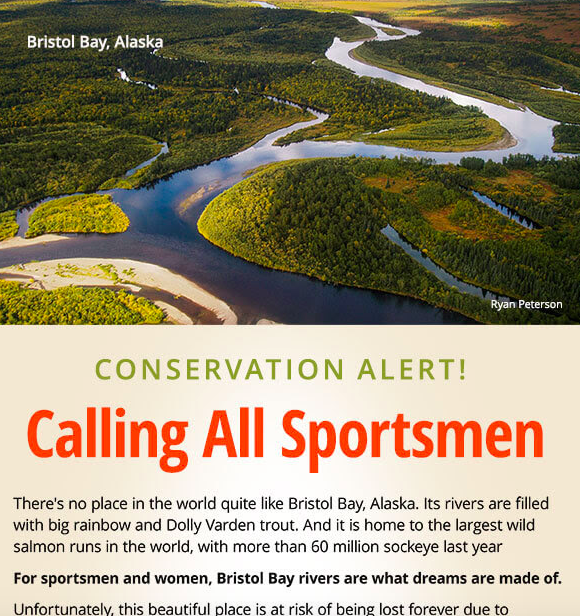

Edgmon interrupted again: “Well madam, if I may just jump in, you also sort of insinuated that the indirect rate was as high as 48 percent. When I watched that, you know, that sort of caught my attention because there are some entities like Northwest Arctic Borough that has an indirect of 9 percent and Bristol Bay Native Association, which has an indirect rate of 15 percent and maybe one of the grantees that actually at that 48 percent range,” he said.

“Rep. Edgmon, through the chair, thank you so much,” Price started. “Thank you for putting forward your frank statement. I find myself in an interesting position where providing data is often taken as insinuation. And just for this body and the purpose of everybody who is in the room and who is listening, I am not a person who insinuates. I make statements so never feel like you have to try read behind the lines. I’m trying to make data statements. The VPSO program is one of the arenas I am responsible for. All of the prongs of public safety are of critical importance.

“Indifference? I think certainly not,” she continued. “I think trying to infer what my attitude or perception is based on data presented is just one of the many challenges that comes with sitting at a microphone and trying to provide data. When I was…”

Edgmon interrupted again to scold her: “If I could jump in please, I would recommend that you choose your words a little bit more artfully, because that was the message that was directly left with me. And I’m somebody who’s been around this building for quite a few years. I’ve seen a number of commissioners in your department come and go. I’m not questioning your dedication and integrity, any of that. But I’m just saying, the message I was left with — me and others — was very different from what I’m hearing you’re trying to portray.”

Edgmon indeed has been around the building for many years, beginning his legislative career as an aide to Sen. George Jacko, who served from 1989-1994.

A few minutes later in the hearing, Edgmon was again dressing Price down, telling her that in her half hour presentation she had not offered one bit of a plan to correct the program. He ignored the fact that she had been interrupted a dozen times at this point. Now visibly angry, he called her presentation “rhetoric.”

“Rep. Edgmon, did you not hear me make the statement earlier that on April 25, we are working with the grantees to deliver what our plan is for the Village Public Safety Officer Program, and how to strengthen it?” Price asked.

Rep. Zulkosky had her moment to also exert her authority: “I would ask the commissioner nominee to manage tone in response to the committee.”

Zulkosky, who had not managed the meeting up until that point, but had allowed it to become a verbal shooting gallery, had finally decided someone had better watch her tone.