A recent ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit means that if a member of any American Indian tribe in Tulsa, Oklahoma wishes to drive 100 miles-per-hour inside a 20-mph school zone, they can do so without worrying about getting a ticket. In fact, American Indians apparently are not subject to any municipal law within some parts of the city.

The 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled last week that the City of Tulsa lacks the jurisdiction to prosecute a Native American man who was cited for speeding on a Tulsa street.

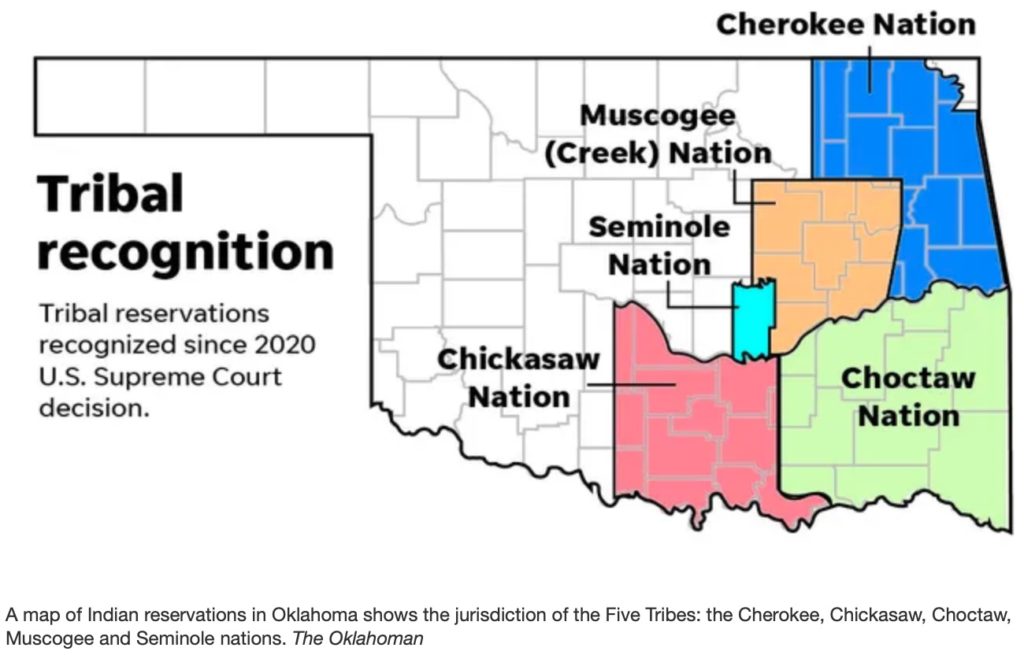

The court’s ruling stems from a Supreme Court decision in 2020 that determined that parts of Tulsa are located within the boundaries of an Indian reservation that had never been disestablished, thus falling under the jurisdiction of tribal law for tribal members rather than municipal law for everyone in the city.

It’s a case that could have legal implications inside the City of Juneau, where there is one parcel of land that Tlingit-Haida has deeded to the federal government as “Indian Country,” and another in Craig, also in Southeast Alaska.

The Oklahoma case involves Justin Hooper, a member of the Choctaw Nation, who was cited for speeding by Tulsa police in 2018. Although Hooper paid the $150 ticket at the time, he later filed a lawsuit challenging the city’s jurisdiction over the offense. Hooper’s attorneys argued that the speeding violation occurred within the historic boundaries of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, rendering it Indian Country and placing it under tribal jurisdiction. Several other tribes filed amicus briefs on Hooper’s behalf, including the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Quapaw, and Seminole nations.

Even though Hooper is Choctaw, he is covered by Muscogee Nation law, the ruling says.

The City of Tulsa contended that the Curtis Act, a federal law passed in 1898, granted the city jurisdiction over municipal violations committed by anyone in its city limits.

However, the appeals court rejected this argument, citing the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2020 decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma. The Supreme Court ,in that case, had ruled that approximately 40% of Oklahoma remains an Indian reservation because it was never formally disestablished by Congress. The McGirt v. Oklahoma ruling essentially shrank the State of Oklahoma’s boundaries by 40%.

The Muscogee Nation, in its brief supporting Native Americans being not subject to municipal or state law in Indian Country, said that without congressional approval, “neither states nor their political subdivisions have jurisdiction over crimes involving Indian defendants committed within the boundaries of an Indian reservation.”

Tulsa officials argued that that the result of a ruling in Hooper’s favor is “a system where municipal laws would only apply to some inhabitants, but not others, depending on a complex algorithm with variables based on tribal membership of a defendant as well as discrete geographies within the City limits. Such a system is clearly more ‘unworkable’ and ‘counterintuitive’ than a clear system where all inhabitants of the City are treated equally for municipal violations.”

The 10th Circuit judges said they could not take the practicality of such an unworkable patchwork of laws into account “even if Tulsa proves correct that reversing the district court’s decision will lead to disruption.”

Tulsa and other municipal courts within the boundaries of Indian reservations must now defer to tribal law when it comes to prosecuting Native Americans for offenses, the ruling says.

Gov. Kevin Stitt spoke about the case last week while addressing his veto of certain Tribal Compacts.

“We want everybody to be successful. I just don’t believe in saying, ‘This group doesn’t have to play by the same set of rules as everybody else. It has nothing against sovereignty. We’ve all been working together since 1907. Let’s keep working together, but let’s not have one set of rules that favors one group over another.”

Stitt’s office also released a statement indicating that this case will now be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court: “I am extremely disappointed and disheartened by the decision made by the Tenth Circuit to undermine the City of Tulsa and the impact it would have on their ability to enforce laws within their municipality. However, I am not surprised as this is exactly what I have been warning Oklahomans about for the past three years. Citizens of Tulsa, if your city government cannot enforce something as simple as a traffic violation, there will be no rule of law in eastern Oklahoma. This is just the beginning. It is plain and simple, there cannot be a different set of rules for people solely based on race. I am hopeful that the United States Supreme Court will rectify this injustice, and the City of Tulsa can rest assured my office will continue to support them as we fight for equality for all Oklahomans, regardless of race or heritage.”

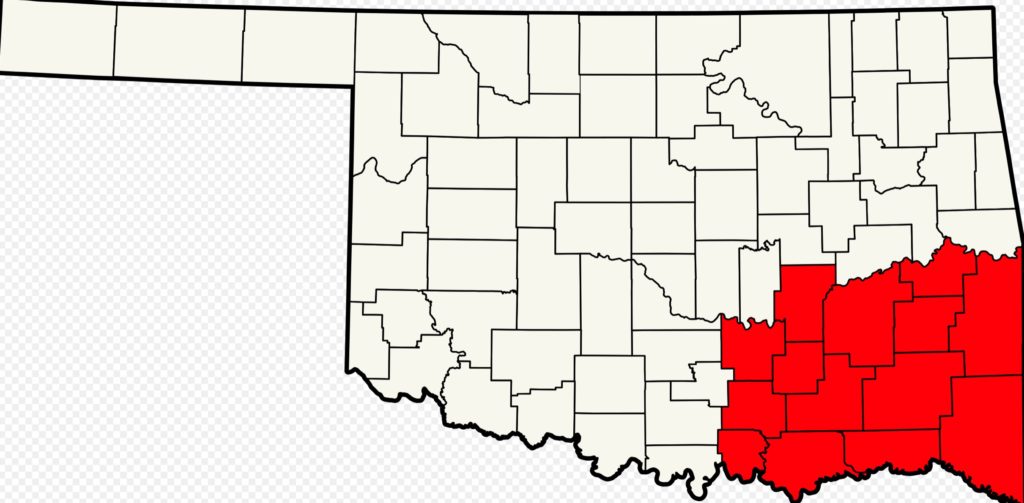

Traditional Choctaw boundaries before McGirt v. Oklahoma, vs. Indian Country established by the 2020 decision.

The Choctaw Nation is the third-largest Native American nation in the United States, with more than 212,000 tribal members and 12,000-plus associates, according to the tribe. Its historic boundaries are in the southeast corner of Oklahoma.

The legal difficulties of the 2020 decision were predicted by many. In 2021, Congress set aside $70 million in additional funding for the U.S. Justice Department to specifically take on the load of justice in 40% of Oklahoma, although at the time Congress did not consider the need for federal law enforcement within Tulsa. The prediction was that the FBI would have to investigate another 7,500 Indian-related cases in the state after McGirt v Oklahoma. Another $10 million was appropriated to the Bureau of Indian Affairs.