By ALEXANDER DOLITSKY

Part 2 of 4 on traditions of Old Believers in Alaska

Marriage among Alaskan and Siberian Old Believers does not have a unified procedure or typical pattern. As a rule, Old Believers, even those in Russia, do not practice venchaniye (i.e., wedding ceremonies under the Russian Orthodox Church traditions), nor do they acknowledge the legitimacy of civil marriage requirements of the state.

The semeyskiye of Trans-Baykal, for example, are divided into many different sects and some of them refuse to recognize Orthodox Church ceremonies. The semeyskiye of the Austrian faction of the popovtsy and Beglopopovtsy, however, confirm their marriages by following Russian Orthodox Church ceremonies, in which the brides are crowned. The semeyskiye-popovtsy, who recognize the authority of the priests of the Orthodox Church, sometimes intermarried with Russian political exiles sent permanently to Siberia by the tsarist government, or with members of the aboriginal population.

Old Believers from Bukhtarmin Fortress in the Altay Mountains (Kamenshchiki) have had prayer halls (molelny dom), but they confirmed their marriages in the Orthodox Church of the Bukhtarmin Fortress. Only bespopovtsy and Temnovertsy (Dark-believers) concords ignore priests, and they confirm marriages not under the church, but in the prayer halls within a secret society.

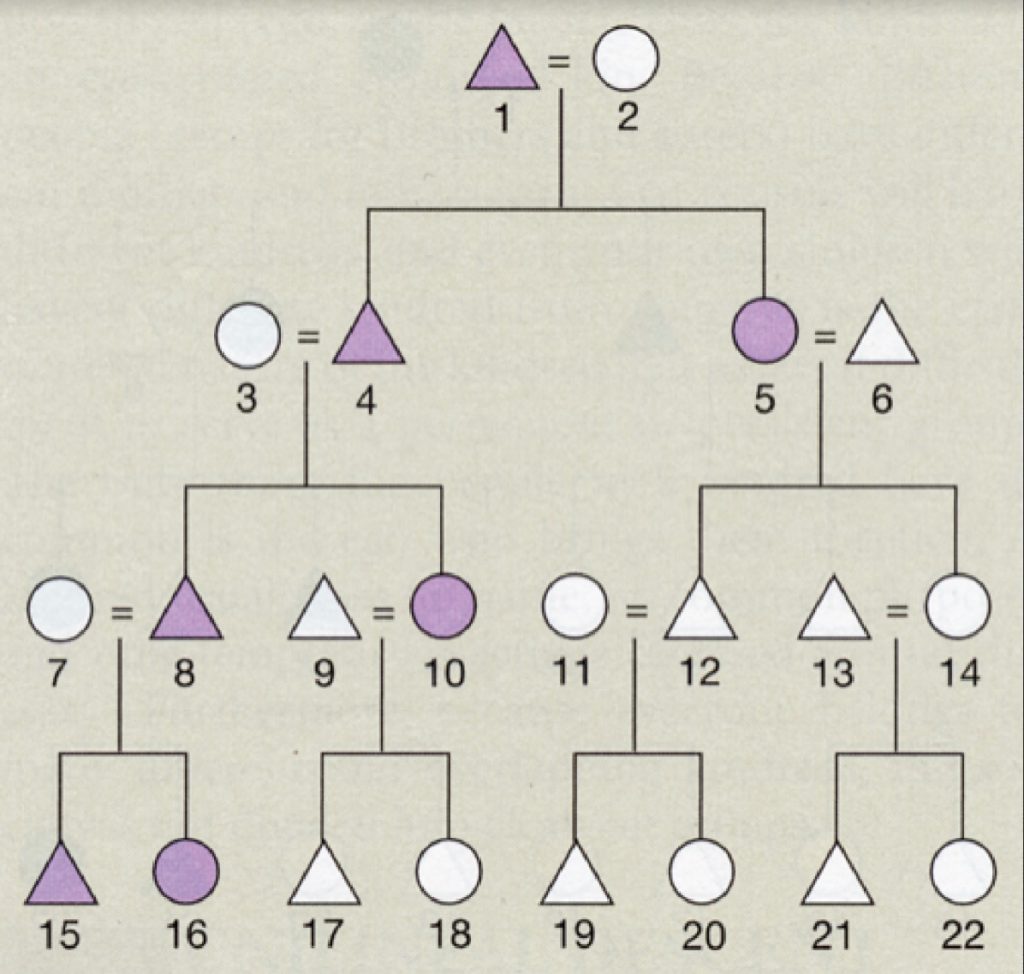

Prior to a marriage, startsy (elders) check and calculate the blood relationship of the youth or marriageable prospects. Numerous rules that prohibit marriage are written in the old books. These regulations are predominantly related to kinship relationships, requiring a four-generation gap (po vosmomu kolenu) between bride and groom, and subsequently reducing the eligible pool even more than the common pan-cultural restrictions, that say a spouse must be approximately the same age (or the man older), the same tolk (religious affiliation), and that both partners have never been married before. Marriage is forbidden if the elder discovers discrepancies or flaws in blood relationships between two prospects.

Old Believers in Alaska are of the patrilineal descent and recognize patrilocal residence. Patrilineal descent affiliates an individual with kin of both sexes related to him or her through men only. In patrilineal systems, as with the Old Believers in Alaska, the children in each generation belong to the kin group of their father; the father, in turn, belongs to the group of his father, and so on.

Although a man’s sons and daughters are all members of the same descent group, affiliation with that group is transmitted only by the sons to their children. Therefore, daughters must leave home when they marry. As Kondratiy Fefelov of Nikolaevsk said, “The son stays and the daughter leaves, so that the married couple lives with or near the husbands’s parents. The parents refuse the warm nest to their daughter (roditeli otkazyvayut tyoploye gnyozdyshko ikh docheri).”

The Orthodox Church permits divorce and remarriage. Certainly, Orthodoxy regards the marriage bond as in principle lifelong and indissoluble, and it condemns the breakdown of marriage as a sin and an evil. But while condemning the sin, the Church still desires to help the sinners and to allow them a second chance.

Old Believers condemn and discourage divorces, but on very rare occasions, when married couples face irreconcilable differences, such as frequent domestic conflicts or chronic and large consumption of alcohol, mostly by male members of the household, the priest of the popovtsy or nastoyatel (layman) of the bespopovtsy will grant a divorce. Nevertheless, as the priest of popovtsy, Kondratiy Fefelov, emphasized during one of our meetings in April of 2001, “…there must be a good reason for a couple to petition for a divorce before the church. The church will not grant a divorce only because couples fall out of love with each other; this is not a good reason for breakdown of a family.”

Wedding Customs and Ceremonies

Weddings are traditional peasant village affairs. Prior to the actual wedding, typical Russian peasant ceremonies such as the engagement negotiations are carried out by the parents of the bride (nevesta) and groom (zhenikh). The final agreement is toasted with presents and a drink. Other ceremonies include devichniki, the time of increased sewing by the bride and her girlfriends, and the evening parties during which the groom and his friends come to call.

There is also the light-hearted “buying of the bride,” in which the groom comes to take her to her new family, and the touching farewell (proshchaniye) of the bride to her parents. The wedding party, with a “chain” of handkerchiefs, proceeds to the prayer hall of bespopovtsy or to the church of popovtsy. The venchaniye, or crowning ceremony, takes place after the regular Sunday service, and the wedding (svadba) is celebrated for three consecutive days at the home of the groom’s father. The bride’s dowry trunk (sunduk) is delivered by her kinsmen and “sold” to the wedding party.

Later, after a meal (pir or obed) the young couple stands for the bowing ceremony (poklony), which is the opportunity for kin to give them wise advice and numerous presents. On the last day of the wedding, the young couple must “buy” the presents from the best man (svidetel) and the matrons of honor with kisses, bows and witticisms. At this point, the bride’s mother-in-law (tyoshcha) is also auctioned off.

Paul J. Wigowsky, a Russian-speaking school teacher with many years of experience in teaching Old Believer students in Hubbard, Oregon, has written an extensive, well-researched and reliable description of Old Believer faith, history, and traditional lifestyles:

“After the regular service has ended, everyone leaves except for the bride, groom, the members of their “chain,” the parents of the bride and groom, the nastoyatyel, and three or four other male witnesses. None of the younger and unmarried people are supposed to see the wedding ceremony itself, and the first wedding an Old Believer sees is usually their own. The bride and groom are asked once again three times if they are marrying of their free will, and if they answer ‘YES,’ then the ceremony begins in earnest. After an initial prayer said in unison, the bride and groom exchange rings, naming each other husband and wife. They are then blessed by their parents, who present them with the icons which have been chosen from among the supplies of both families, to be given to the newlyweds for their own household. While the blessings are being administered, the couple kneels before the parents of both families.

“After this, the bride is taken to the back of the church where her marriage-cap (shashmura) and scarves are laid out on a dresser. She removes her krassota (the crown), which she has been wearing all through the ceremony, and the bridesmaids then plait her hair into two braids, tie them up over her head, and place the shashmura over it and two scarves over that. The bride is now given the appearance of a married woman, since unmarried women and girls wear their hair in a single braid down the back. She is never to show her hair to any man other than her husband, according to traditional decree.

“She then proceeds to the groom, and bows before him to the floor, and kisses him. This is to indicate, symbolically, that she is now his and that she will be loyal and submissive toward him for the rest of her days. The “chain” then forms again, while the nastoyatyel reads the portions of the sacred texts which describe the duties of wife and husband toward each other and toward their future children. The bride then says a prayer and asks her parents their forgiveness for leaving them to become a member, in essence, of the groom’s family. After a closing group prayer, the ceremony is finished and the people go to the groom’s house for breakfast.”

Because weddings are meant to be elaborate, plentiful and lavish, they cannot be held on any of the fast days or during the Lenten periods. This tends to make the wedding a seasonal event, normally scheduled just before the 7-week Easter Lent. The groom’s family prepares a variety of foods and makes sure that they have plenty of home-made alcoholic drink — braga.

Alexander B. Dolitsky was born and raised in Kiev in the former Soviet Union. He received an M.A. in history from Kiev Pedagogical Institute, Ukraine, in 1976; an M.A. in anthropology and archaeology from Brown University in 1983; and was enroled in the Ph.D. program in Anthropology at Bryn Mawr College from 1983 to 1985, where he was also a lecturer in the Russian Center. In the U.S.S.R., he was a social studies teacher for three years, and an archaeologist for five years for the Ukranian Academy of Sciences. In 1978, he settled in the United States. Dolitsky visited Alaska for the first time in 1981, while conducting field research for graduate school at Brown. He lived first in Sitka in 1985 and then settled in Juneau in 1986. From 1985 to 1987, he was a U.S. Forest Service archaeologist and social scientist. He was an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Russian Studies at the University of Alaska Southeast from 1985 to 1999; Social Studies Instructor at the Alyeska Central School, Alaska Department of Education from 1988 to 2006; and has been the Director of the Alaska-Siberia Research Center (see www.aksrc.homestead.com) from 1990 to present. He has conducted about 30 field studies in various areas of the former Soviet Union (including Siberia), Central Asia, South America, Eastern Europe and the United States (including Alaska). Dolitsky has been a lecturer on the World Discoverer, Spirit of Oceanus, andClipper Odyssey vessels in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. He was the Project Manager for the WWII Alaska-Siberia Lend Lease Memorial, which was erected in Fairbanks in 2006. He has published extensively in the fields of anthropology, history, archaeology, and ethnography. His more recent publications include Fairy Tales and Myths of the Bering Strait Chukchi, Ancient Tales of Kamchatka; Tales and Legends of the Yupik Eskimos of Siberia; Old Russia in Modern America: Russian Old Believers in Alaska; Allies in Wartime: The Alaska-Siberia Airway During WWII; Spirit of the Siberian Tiger: Folktales of the Russian Far East; Living Wisdom of the Far North: Tales and Legends from Chukotka and Alaska; Pipeline to Russia; The Alaska-Siberia Air Route in WWII; and Old Russia in Modern America: Living Traditions of the Russian Old Believers; Ancient Tales of Chukotka, and Ancient Tales of Kamchatka.

A few of Dolitsky’s past MRAK columns:

Read: Neo-Marxism and utopian Socialism in America

Read: Old believers preserving faith in the New World

Read: Duke Ellington and the effects of Cold War in Soviet Union on intellectual curiosity

Read: United we stand, divided we fall with race, ethnicity in America

Read: For American schools to succeed, they need this ingredient

Read: Nationalism in America, Alaska, around the world

Read: The case of the ‘delicious salad’

Read: White privilege is a troubling perspective

Read: Beware of activists who manipulate history for their own agenda

Read: Alaska Day remembrance of Russian transfer

Read: American leftism is true picture of true hypocrisy

Read: History does not repeat itself

Read: The only Ford Mustang in Kiev