By ALEXANDER DOLITSKY

Translators and interpreters use their knowledge of two or more languages and cultural meanings to translate or interpret texts and conversations from one language to another, to enhance communication across cultures and the parties involved.

The difference between a translator and an interpreter is how they perform their job duties. Translators convert one language to another in a written form (e.g., documents, film subtitles, books). In contrast, interpreters translate languages simultaneously through spoken words (e.g., meeting with clients in-person and attending negotiations). Also, on many occasions, interpreters play an essential role as assistants and troubleshooters behind the scenes.

For nearly 40 years, I performed both functions as a translator and interpreter of Russian for various government institutions, businesses, non-profit organizations, and private individuals. Although interpreting languages is a highly technical skill, it is also a communication task that ensures a successful cross-cultural engagement and understanding for all. In fact, unqualified interpretation can create a conflicting outcome and cross-cultural misunderstanding for those who rely on interpretation; and vice versa—a professional interpretation can lead to a successful outcome.

For example, in 1977, during U.S. President Jimmy Carter’s visit to Poland, a segment of his speech was incorrectly interpreted. The interpreter said President Carter wanted to learn about the Polish people’s “desires for the future,” which translated into a sexual desire for the then-Socialist country, instead of the country’s “aspiration for the future,” a hope or ambition of achieving something in the future.

From 1946 to the mid-1980s, Alaska was closed for Soviet citizens, except for some scholarly exchanges between two regions. During this time of the “Iron Curtain,” both nations were an enigma to one another and often subjected to dubious behaviors toward each other.

Nevertheless, initial visits of official Soviet delegations to Alaska in the 1980s and early 1990s, generated an enormous interest and excitement among all spectrum of Alaska’s residents (e.g., government institutions, businesses, educators, private individuals, etc.). In my practice as an interpreter in Alaska, three different occurrences clearly exemplified the complexity of responsible interpretations and the need for quick adaptation to an unpredictable turn of events.

The governor of the Magadan Region of the former Soviet Union, Vyacheslav Kobets, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Magadan Region, and a special envoy from Moscow visited Alaska in February of 1989. The delegation of Soviet officials and I, as an interpreter, were invited to visit the Alaska Legislature in Juneau.

While at the guest gallery of the House Chamber, then-Speaker of the House Sam Cotten welcomed the Soviet delegation. Unexpectedly, Governor Kobets stood up, pulled out several long-typed pages of text and, from the gallery, began addressing the Legislature in the Russian language.

The legislators and I were not prepared for such a turn of events. I immediately began a simultaneous translation without prior familiarity with the text. Kobets’ presentation lasted about 40 minutes and, evidently, it delayed the working agenda of the House’s session that day.

Nevertheless, all legislators listened to Kobets’ presentation via my translation attentively and patiently. I noticed, however, that the special representative from Moscow was visibly nervous during the presentation; he understood that Kobets lacked knowledge of the proper protocol.

In the early stages of the Russian-Alaskan exchanges, both sides went through a learning curve of reciprocal cultural and business familiarity with each other—sometimes quite awkward and sometimes humorous. My friend David Marshall was an economist in Juneau in the 1980s and 1990s. He, as well as many Alaskans, traveled to the Soviet Union on several occasions with the purpose of establishing a lucrative business with Russian entrepreneurs. In the early-1990s, he got acquainted with Boris from Magadan; Boris appeared to David as an enthusiastic and well-connected businessman. When Boris arrived in Juneau, they met at the Fiddlehead Restaurant to discuss David’s carefully drafted business proposal for a joint venture. (Evidently, David and Boris previously discussed establishing a financial investment company—a hedge fund—prior to the meeting in Juneau).

At some point during the meeting, Boris leaned toward David and suggested, “Listen, David, why complicate our business with this hedge fund? Instead, we can simply sell shampoo and make a good profit.” For a moment, David was puzzled by this unexpected suggestion. “And can you explain to me where and how the profit will come from by selling shampoo?” David asked suspiciously. “It is simple. We will dilute the shampoo with about 20 percent water,” answered Boris with a smirk smile. “In Magadan, no one will even notice a difference, and the product will fly off the shelves very quickly,” he continued.

Suddenly, David erupted like an ancient volcano after centuries of “hibernation,” angrily tearing the business proposal in pieces and throwing them in the air like a party confetti. All the guests in the restaurant turned their attention toward our table, each with an obvious curiosity about the commotion. All I could think at this moment, “There goes $60 per hour for my interpretation services.” Indeed, this was last meeting between these two enthusiastic businessmen. I was not paid for my efforts, and I was not daring enough to ask for it.

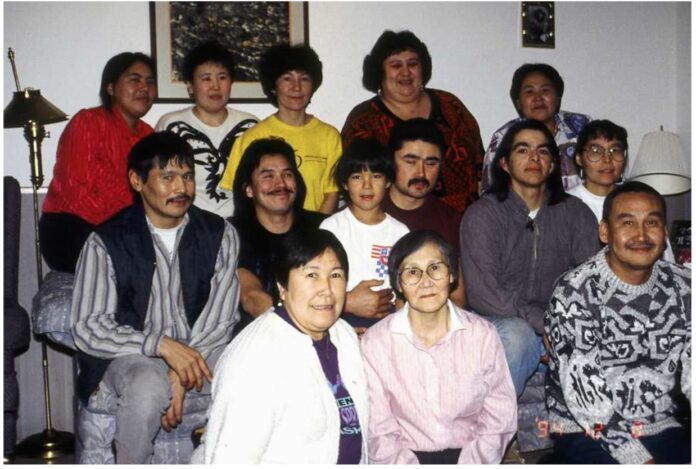

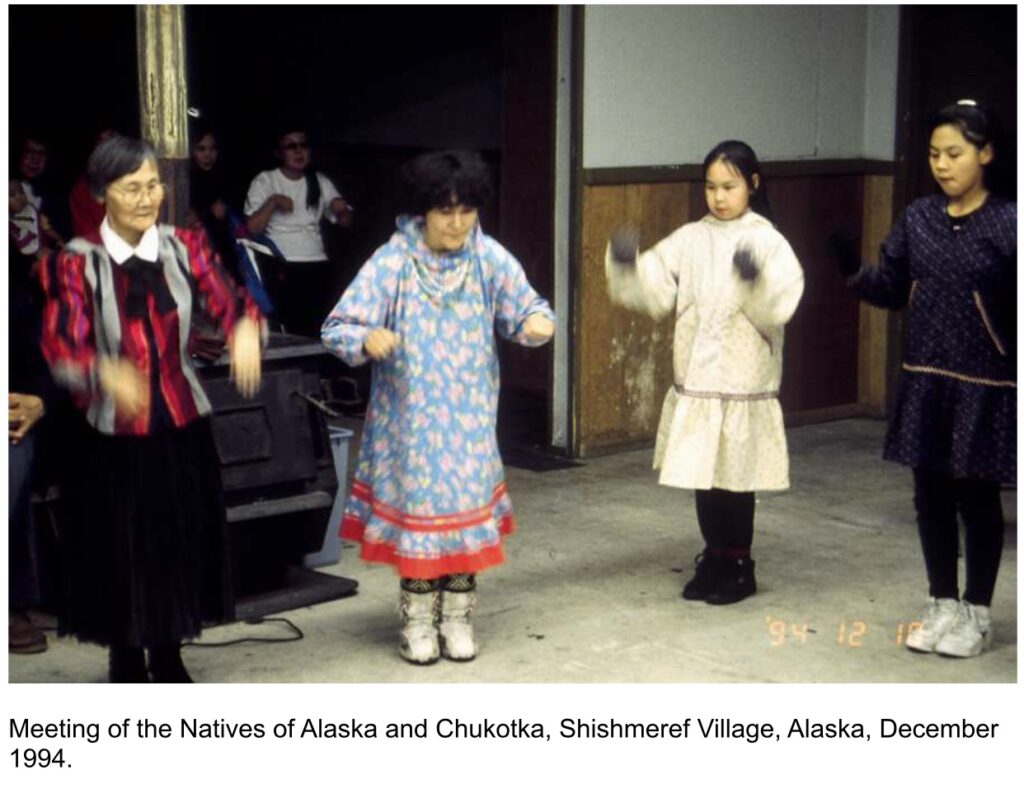

In December of 1994, I was hired to interpret for meetings between Natives of Alaska and Natives of the Russian Far East. The meetings were held in White Mountain Village and Shishmaref Village of Northwest Alaska under auspices of the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services and Eurasian Foundation.

The topics of the meetings were rather dramatic, emotional and urgent among Natives of both regions — alcoholism, diabetes, botulism, suicide, family abuses, mental illness, and various health-related issues. The participants shared their painful experiences, and I did my best in interpreting the information. Although Alaska Yupik and Inupiaq have close cultural and linguistic similarities with the Siberian Yupik and Chukchi, they could not fluently understand each other’s unique languages.

At one point of working with the Natives in Shishmaref Village, an elderly Alaskan Yupik woman approached me with a concern about my interpretations, “I do not like your translation,” she declared boldly. “Why?” I asked. “You do not translate our feelings,” she answered in a demanding voice, staring directly into my face. “I understand how you feel but interpreters translate words, sentences and contents, not emotions, feelings or attitudes,” I responded delicately. Her body language and facial expression gave me a distinct impression that she did not appreciate my explanation or my role at the meeting. Indeed, after 10 days of working above the Arctic Circle in December, I was relieved to return to my home in Juneau.

In my observation, the majority of the left-leaning progressive activists had impulsively initiated poorly-thought out exchanges with the former Soviet Union in the 1980s and early 1990s. Ironically, the left-leaning progressive activists went in the opposite directions after Russian annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 in supporting harsh and irrational sanctions upon the Russian Federation; which ultimately led to the rise of radical nationalism in Ukraine and, subsequently, led to the Russian-Ukrainian war of February 2022 until today.

After all, how many decades will it take to restore friendly and constructive relationship with our neighbor—Russia? It will take more than a skillful interpreter, it appears, because the two sides are far beyond the translation of “feelings” at this point in the conflict.

Alexander B. Dolitsky was born and raised in Kiev in the former Soviet Union. He received an M.A. in history from Kiev Pedagogical Institute, Ukraine, in 1976; an M.A. in anthropology and archaeology from Brown University in 1983; and was enroled in the Ph.D. program in Anthropology at Bryn Mawr College from 1983 to 1985, where he was also a lecturer in the Russian Center. In the U.S.S.R., he was a social studies teacher for three years, and an archaeologist for five years for the Ukranian Academy of Sciences. In 1978, he settled in the United States. Dolitsky visited Alaska for the first time in 1981, while conducting field research for graduate school at Brown. He lived first in Sitka in 1985 and then settled in Juneau in 1986. From 1985 to 1987, he was a U.S. Forest Service archaeologist and social scientist. He was an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Russian Studies at the University of Alaska Southeast from 1985 to 1999; Social Studies Instructor at the Alyeska Central School, Alaska Department of Education from 1988 to 2006; and has been the Director of the Alaska-Siberia Research Center (see www.aksrc.homestead.com) from 1990 to present. He has conducted about 30 field studies in various areas of the former Soviet Union (including Siberia), Central Asia, South America, Eastern Europe and the United States (including Alaska). Dolitsky has been a lecturer on the World Discoverer, Spirit of Oceanus, andClipper Odyssey vessels in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. He was the Project Manager for the WWII Alaska-Siberia Lend Lease Memorial, which was erected in Fairbanks in 2006. He has published extensively in the fields of anthropology, history, archaeology, and ethnography. His more recent publications include Fairy Tales and Myths of the Bering Strait Chukchi, Ancient Tales of Kamchatka; Tales and Legends of the Yupik Eskimos of Siberia; Old Russia in Modern America: Russian Old Believers in Alaska; Allies in Wartime: The Alaska-Siberia Airway During WWII; Spirit of the Siberian Tiger: Folktales of the Russian Far East; Living Wisdom of the Far North: Tales and Legends from Chukotka and Alaska; Pipeline to Russia; The Alaska-Siberia Air Route in WWII; and Old Russia in Modern America: Living Traditions of the Russian Old Believers; Ancient Tales of Chukotka, and Ancient Tales of Kamchatka.

Read: Russian Old Believers in Alaska live lives reflecting bygone centuries

Read: Russian saying: Beat your friends so your enemies fear you

Read: Neo-Marxism and utopian Socialism in America

Read: Old believers preserving faith in the New World

Read: Duke Ellington and the effects of Cold War in Soviet Union on intellectual curiosity

Read: United we stand, divided we fall with race, ethnicity in America

Read: For American schools to succeed, they need this ingredient

Read: Nationalism in America, Alaska, around the world

Read: The case of the ‘delicious salad’

Read: White privilege is a troubling perspective

Read: Beware of activists who manipulate history for their own agenda

Read: Alaska Day remembrance of Russian transfer

Read: American leftism is true picture of true hypocrisy

Read: History does not repeat itself

Read: The only Ford Mustang in Kiev

Read: What is greed? Depends on the generation

Read: Worldwide migration of Old Believers in Alaska

Read: Traditions of Old Believers in Alaska

Read: Language, Education of Old Believers in Alaska