By TIM BARTO

A couple decades ago, my wife and I took our children to Hawaii to attend a wedding on my wife’s side of the family. Born and raised on Oahu, my wife is an ethnic conglomeration of Japanese, Okinawan, and Filipina; a “poi mix,” as she calls it in her occasional pidgin recollections.

We’d been married several years by that time, and I’d done my job bringing some really cute hapa-haole grandchildren into the family lineage, so I was feeling pretty confident as we attended a post-wedding get-together at one of my in-laws’ house.

The ladies gathered in the family room while the men sat at the kitchen table. This was my first gathering among so many in-laws, and I felt privileged to be hanging out with the fellas. I had made it to the inner sanctum. My wife’s 80-year-old grandmother, Baban, was following tradition by staying in the kitchen and serving pupus and drinks to the men.

Reaching into that confidence, I thought I would conduct some family history research. As I am wont to do with anyone of the World War II generation, I asked Baban, “What was it like being Japanese here during the War?”

Silence.

The male in-laws looked at each other and started to smile. Had I made a social faux pas? Did I broach sensitive territory? Were fists going to be thrown

After about three or four seconds, Baban spun around, hot frying pan in one hand and an accusatory finger pointing at me with the other.

“I not Japanee. I Okinawan!”

Snickers from my in-laws preceded a five minute lecture on the difference between Japanese and Okinawans, with emphasis on how the Japanese subjugated the Okinawans for far too long. Baban, it turns out, had left Hawaii to visit relatives in Okinawa. But that was December of 1941, so she was unable to return to the United States until after the War ended. She spent those four years in Japanese-occupied Okinawa.

This four-foot-nine-inch octogenarian put her ignorant “haole” grandson-in-law in his place. Lesson learned.

Sort of.

A few nights later, we were at my father-in-law’s backyard for a barbecue, and his father, Sugar, joined us. Changing my tactic slightly, I asked Grandpa Sugar what he did during the War.

Sugar, who’d had a couple beers, followed by a few beers, and was now working on several beers, looked down and waved his hand toward me. “Ah, nothing much.”

Being a glutton for punishment, I pressed on. “Come on, Grandpa, I want to know the family history. What did you do during World War II?”

Again, he waved me off. Then he took a long swig from his can of beer and said, “I was with the 442nd.”

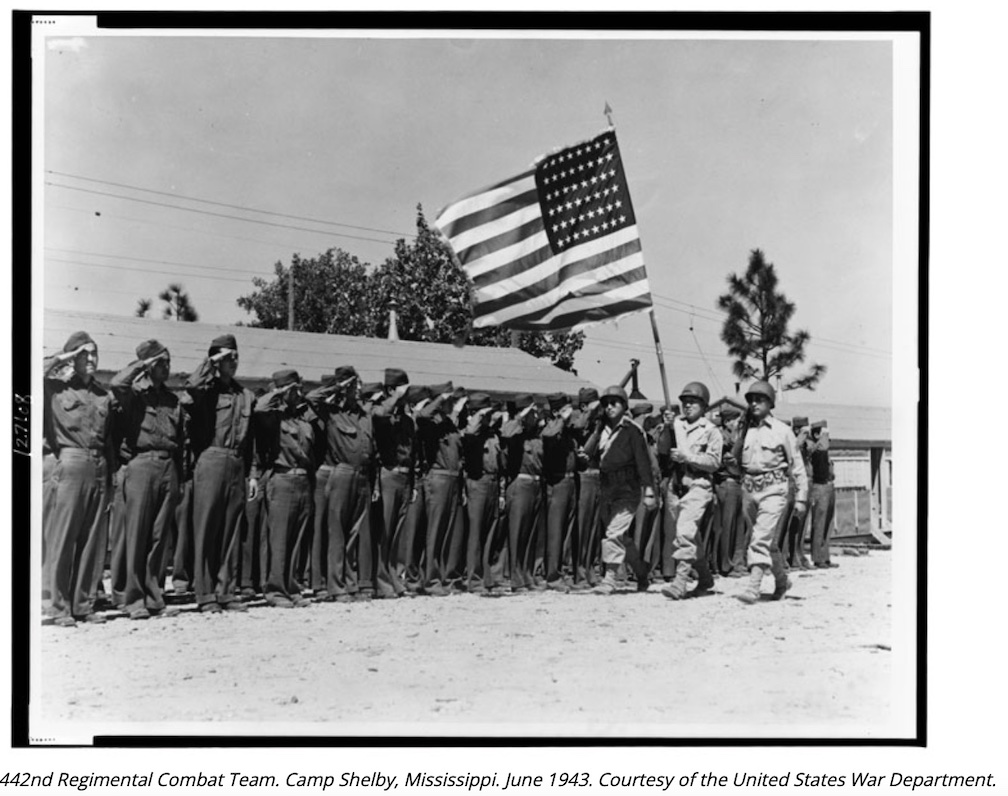

My eyes grew wide, and chills ran up my arms. Hell, chills are running up my arms as I’m typing this. My grandfather-in-law served in the all Japanese-American 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the most highly decorated American unit of its size during the War!

I looked to my wife and her brother, and they were concentrating on the kalbi and spam musubis. Maybe they were tired of hearing these old war stories. “You guys knew this? Why didn’t you tell me?” I asked.

“What was the 442nd?” they wanted to know. Amazingly, these grandchildren of a Nisei soldier never learned the phenomenally unique story of what their relatives did during World War II.

They have now. And so do my children. They should know what courage and honor are, and how an ethnic group served this great country even while many of that same ethnic group had their homes and livelihoods taken away from them simply because they belonged to that ethnic group.

This was not theoretical prejudice. This was blatant and it was instituted by the federal government. Yet, despite the unfairness of it all, brave men proved their mettle and their loyalty as American citizens, and humbly and with great honor, fought, bled, and died for their country.

Tim Barto is vice president of Alaska Policy Forum, and still pesters members of The Greatest Generation about what they did during the War.

Read more about the 442nd at this link:

https://www.goforbroke.org/learn/history/military_units/442nd.php