By ALEXANDER DOLITSKY

Without a doubt, Lend-Lease food proved vital to the maintenance of adequate nutrition levels for Soviets and other Lend-Lease beneficiaries. In 1944, 2% of the United States’ food supply was exported to the Soviet Union, 4% to other 42 Lend-Lease recipients, 1% to commercial exports, and 13% to the 12 million in the United States military who participated in the war between 1941 and 1945.

This aid was made possible due to sacrifices made by the American people and an enormous increase in American agricultural and industrial production—up 280% by 1944 over the 1935–39 average.

About $11 billion in war materials and other supplies were shipped to the Soviet Union from the United States over four major routes between 1941 and 1945. In addition to military equipment, the USSR received non-military items like cigarettes, records, women’s compacts, fishing tackle, dolls, playground equipment, cosmetics, food, and even 13,328 sets of false teeth.

Soviet requests for food emphasized canned meat (tushonka), fats, dried peas and beans, potato chips, powdered soups and eggs, dehydrated fruits and vegetables, and other packaged food items. Dehydration, which made shipping food to the Soviet Union possible under the program, led to a rapid expansion of American dehydrating facilities, which eventually influenced the domestic market and the diet of American people in the post-war period until today.

Lend-Lease accounts show that, in 1945 alone, about 5,100,000 tons of foodstuffs left for the Soviet Union from the United States; that year, the Soviets’ own total agricultural output reached approximately 53,500,000 tons.

If the 12 million individual members of the Soviet Army received all the foodstuffs that arrived in the USSR through Lend-Lease deliveries from the United States, each man and woman would have been supplied with more than half a pound of concentrated food per day for the duration of the war.

Post-World War II changes in food production, supply and dietary guidelines were significantly influenced by wartime rationing, technological advancements and changing consumer preferences. The war led to rationing and shifts in food availability, while also spurring the development of new food technologies and influencing consumer preferences. These factors, combined with the rise of food marketing, dramatically altered the American diet.

Rationing to ensure equitable distribution of scarce resources significantly impacted food availability and consumption patterns. Rationing of items like sugar, coffee, meat, and butter altered what foods were readily available and how they were prepared. Rationing encouraged the use of less expensive cuts of meat and the creation of recipes that stretched the available meat supply, such as meatloaf and stuffed peppers. Frozen food, previously not widely adopted, gained traction during the war due to rationing and the need for longer-lasting food storage.

New technologies developed during the war in food preservation and packaging led to the rise of industrially processed foods. Convenience foods became more prevalent as the emphasis shifted towards ease of preparation and speed; however, often at the expense of nutritional value. Home appliances like refrigerators and freezers became more common, further impacting food storage and preparation methods.

Exposure to new and different cuisines during the war expanded American palates and led to the adoption of new flavors, dishes and changing consumer preferences. Subsequently, food companies invested heavily in advertising and marketing, influencing consumers’ food choices and creating demand for processed foods. The rise of chain restaurants and fast food further altered eating habits, emphasizing speed and convenience over nutritional value.

In summary, the post-war period saw a complex interplay of factors that dramatically changed the American diet and the way we approach food today. Rationing during the war, technological advancements in food production and supply, and evolving scientific understanding of nutrition all contributed to the shift towards a more processed and convenience-driven food culture. This, in turn, led to the development of dietary guidelines that emphasized nutrient adequacy and, eventually, the prevention of chronic diseases.

The negative outcome of the post-war food production and supply have been an undeniable obesity of the American population of all ages, ethnicities and social groups. Two dramatic examples can be found in architectural changes. Due to changes in the food production in post-war America, enhancements were required in the seats of two iconic American venues—the Lincoln and Ford Theatres in Washington D.C. This was a direct result of a rapid enlargement and obesity of the American population.

The Lincoln Theatre is a historic venue that opened in 1922 and was once a hub for entertainment. The Theatre has undergone several renovations throughout its history, with significant work done in the 1990s and more recently in the 2020s. These renovations aimed to restore the historic theater of the 1920s, enhance accessibility, and improve amenities for both patrons and performers. One of the key renovations and improvements included installing new, enhanced and cushioned seats suitable for today’s enlarged American audience.

Similar seat renovations took place in the Ford Theatre; the original chairs were replaced with larger, more modern seats in the late 1970s and early 1980s because the original replicas were deemed too small and uncomfortable by audiences. The original chairs in Ford’s Theatre, installed in 1865, were cane-bottomed, high-backed wooden chairs. These were replaced with replicas in 1968 during the restoration. The replica chairs were found to be uncomfortable, leading to their replacement with larger, more modern seats in the late 70s/early 80s. They are significantly larger 1900s-style chairs from another theater, installed in 2009-2010 to accommodate today’s Americans.

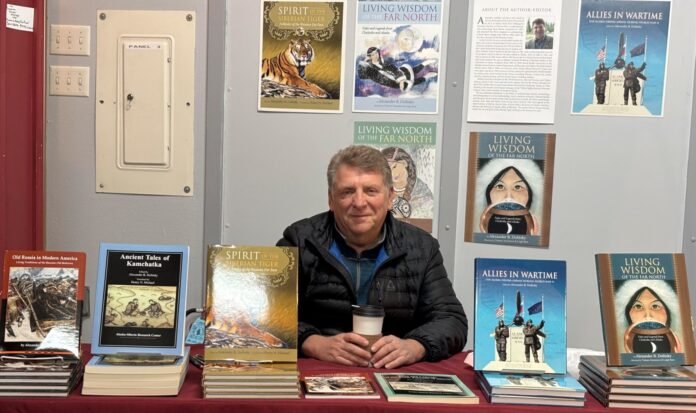

Alexander Dolitsky was born and raised in Kiev in the former Soviet Union. He received an M.A. in history from Kiev Pedagogical Institute, Ukraine in 1976; an M.A. in anthropology and archaeology from Brown University in 1983; and enrolled in the Ph.D. program in anthropology at Bryn Mawr College from 1983 to 1985, where he was also lecturer in the Russian Center. In the USSR, he was a social studies teacher for three years and an archaeologist for five years for the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. In 1978, he settled in the United States. Dolitsky visited Alaska for the first time in 1981, while conducting field research for graduate school at Brown. He then settled first in Sitka in 1985 and then in Juneau in 1986. From 1985 to 1987, he was U.S. Forest Service archaeologist and social scientist. He was an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Russian Studies at the University of Alaska Southeast from 1985 to 1999; Social Studies Instructor at the Alyeska Central School, Alaska Department of Education and Yukon-Koyukuk School District from 1988 to 2006; and Director of the Alaska-Siberia Research Center from 1990 to 2022. From 2006 to 2010, Alexander Dolitsky served as a Delegate of the Russian Federation in the United States for the Russian Compatriots program. He has done 30 field studies in various areas of the former Soviet Union (including Siberia), Central Asia, South America, Eastern Europe and the United States (including Alaska). Dolitsky was a lecturer on the World Discoverer, Spirit of Oceanus, and Clipper Odyssey vessels in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic regions. He was a Project Manager for the WWII Alaska-Siberia Lend Lease Memorial, which was erected in Fairbanks in 2006. Dolitsky has published extensively in the fields of anthropology, history, archaeology and ethnography. His more recent publications include Fairy Tales and Myths of the Bering Strait Chukchi, Ancient Tales of Kamchatka, Tales and Legends of the Yupik Eskimos of Siberia, Old Russia in Modern America: Living Traditions of the Russian Old Believers in Alaska, Allies in Wartime: The Alaska-Siberia Airway During World War II, Spirit of the Siberian Tiger: Folktales of the Russian Far East, Living Wisdom of the Russian Far East: Tales and Legends from Chukotka and Alaska, and Pipeline to Russia: The Alaska-Siberia Air Route in World War II.