By ALEXANDER DOLITSKY

The two most important Jewish holidays are Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) and Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), which are considered the “High Holy Days” and are celebrated as a period of reflection and repentance. Rosh Hashanah is a two-day traditional Jewish holiday. This year it will be celebrated Oct. 2-4 as the start of the Jewish New Year.

In the Jewish theological tradition, Rosh Hashanah is the birthday of the world, when God created the world 5,784 years ago. The literal translation of Rosh Hashanah is “Head of the Year.” It is named to emulate the human head controlling its body; the day of Rosh Hashanah affects the whole year.

In connection with the upcoming Rosh Hashanah in October, it is imperative to remind the world about the prominent Jewish artist Marc Chagall, representing a symbol of peace and mutual healing. Mutual healing is the one element Jews long for the most; it’s a process in which all parties grow and change; and there is a deep healing in the relationship between people.

Marc Chagall (Moshe Segal) was born July 7, 1887, in Vitebsk, Belorussia, Russian Empire (now Belarus) and died March 28, 1985, in Saint-Paul, Alpes-Maritimes, France.

In 1906, at the age of 19, he left his hometown Vitebsk to live in St. Petersburg, then the center of the Russian intellectual and artistic world. In St. Petersburg, he studied at the Imperial School for the Protection of the Fine Arts and at the Zvantseva School of Drawing and Painting under renowned Russian artists of the time, including Léon Bakst.

In May 1911, Chagall arrived in Paris, where he enrolled at the Académie de La Palette and settled at La Ruche studios in Montparnasse in the south of Paris, mixing with other Jewish immigrant artists, including Amedeo Modigliani and Chaim Soutine; as well as key figures in French modernism, among them Guillaume Apollinaire and Robert Delaunay.

Chagall was destined to become the eminent painter (illustrator) of the most complete edition of the Hebrew Bible (i.e., Christian Old Testament). The Hebrew Bible, also known as the Tanakh, is made up of a collection of ancient writings in Hebrew and Aramaic languages.

Indeed, Chagall’s art was mainly inspired by the Hebrew Bible throughout his entire life. His unique combination of surrealism, cubism, Russian folk traditions and Fauvism propelled him to the top of the artists’ community in Paris.

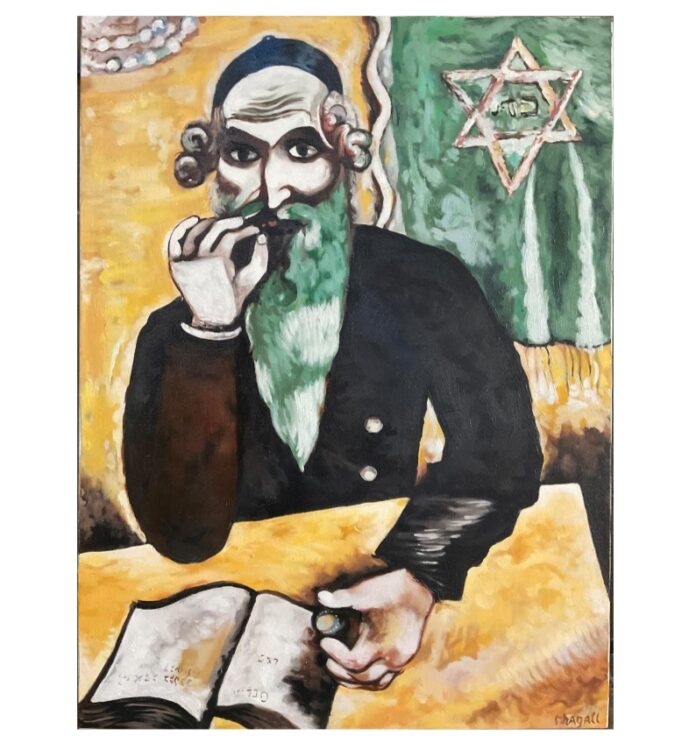

Chagall’s Orthodox Hasidic upbringing and family roots with strong religious traditions are evident in his paintings, such as “Pinch of Snuff.” This piece depicts a Hasidic Jew in a traditional attire, sitting quietly and chewing a “magic potion” (tobacco) that brings emotional happiness and fictional fantasy.

According to an ancient Hasidic parable, “… when the flow of God’s love poured out into the earth’s basin, it broke into countless fragments of individual things, in each of which still lives a spark of divine love.” Chagall intended to capture this spark of love in his art.

“Pinch of Snuff,” seem above, is currently exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In the upper left, a pearl necklace evokes the threads of Chagall’s childhood days in the Hasidic community in Vitebsk. A black yarmulka (a skull cap worn in public by Orthodox Jewish men or during prayer by other Jewish men) masters his yellow curls. In the background, the golden star of David glows over a curtain of intense green color, symbolizing Chagall’s hope for a better future, as he expresses in his prayer:

“God, You who hide in the clouds, or behind the shoemaker’s house, bare my soul, the aching soul of a stuttering child, show me my way. I don’t want to be like everyone else; I want to see a new world. “

Marc Chagall left his unique mark on modern art with his colorful works, encompassing surrealism, neo-primitivism and Fauvism. Throughout his 75-year career, he produced nearly 10,000 works — warm, human pictorial universe, full of personal metaphors, inspired by Jewish traditions, Russian fairy tales, and his own delirious dreams.

He is the one who created the majestic ceiling of the Opéra Garnier in Paris and The Sources of Music and The Triumph of Music murals painted in 1966 for the Metropolitan Opera House at the Lincoln Center in New York City. After his death in 1985, the artist left behind an impressive artistic heritage and colossal legacy of love and peace for all humanity.

Let us pray like Marc Chagall for the world peace and harmony that Elias (a Hebrew prophet) will bring. Shabbat Shalom with love to all.

Marc Chagall: “Despite all the troubles of our world, in my heart I have never given up on the love in which I was brought up or on man’s hope in love. In life, just as on the artist’s palette, there is but one single color that gives meaning to life and art—the color of love.”

Alexander B. Dolitsky was born and raised in Kiev in the former Soviet Union. He received an M.A. in history from Kiev Pedagogical Institute, Ukraine, in 1976; an M.A. in anthropology and archaeology from Brown University in 1983; and was enroled in the Ph.D. program in Anthropology at Bryn Mawr College from 1983 to 1985, where he was also a lecturer in the Russian Center. In the U.S.S.R., he was a social studies teacher for three years, and an archaeologist for five years for the Ukranian Academy of Sciences. In 1978, he settled in the United States. Dolitsky visited Alaska for the first time in 1981, while conducting field research for graduate school at Brown. He lived first in Sitka in 1985 and then settled in Juneau in 1986. From 1985 to 1987, he was a U.S. Forest Service archaeologist and social scientist. He was an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Russian Studies at the University of Alaska Southeast from 1985 to 1999; Social Studies Instructor at the Alyeska Central School, Alaska Department of Education from 1988 to 2006; and has been the Director of the Alaska-Siberia Research Center (see www.aksrc.homestead.com) from 1990 to present. He has conducted about 30 field studies in various areas of the former Soviet Union (including Siberia), Central Asia, South America, Eastern Europe and the United States (including Alaska). Dolitsky has been a lecturer on the World Discoverer, Spirit of Oceanus, and Clipper Odyssey vessels in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. He was the Project Manager for the WWII Alaska-Siberia Lend Lease Memorial, which was erected in Fairbanks in 2006. He has published extensively in the fields of anthropology, history, archaeology, and ethnography. His more recent publications include Fairy Tales and Myths of the Bering Strait Chukchi, Ancient Tales of Kamchatka; Tales and Legends of the Yupik Eskimos of Siberia; Old Russia in Modern America: Russian Old Believers in Alaska; Allies in Wartime: The Alaska-Siberia Airway During WWII; Spirit of the Siberian Tiger: Folktales of the Russian Far East; Living Wisdom of the Far North: Tales and Legends from Chukotka and Alaska; Pipeline to Russia; The Alaska-Siberia Air Route in WWII; and Old Russia in Modern America: Living Traditions of the Russian Old Believers; Ancient Tales of Chukotka, and Ancient Tales of Kamchatka.