Alaska’s Senate Resources Committee convened on Tuesday, January 26, to dissect the state’s natural gas export ambitions through the lens of Canada’s LNG Canada project, a rare success story in the North American LNG sector. With developer Glenfarne Group signaling renewed momentum toward a pipeline and export facility from the North Slope to Nikiski, lawmakers sought clarity on fiscal frameworks, cost overruns, tax incentives, and project readiness. Consultants from GaffneyCline—energy advisory firm Senior Director of LNG and Energy Transition Nicholas Fulford and Director of Facilities and Cost Andrew Duncan—delivered detailed testimony, highlighting contrasts between Canada’s approach and Alaska’s evolving proposal.

The LNG Canada project, located in Kitimat on British Columbia’s mid-coast, has become a benchmark for Pacific-facing LNG developments. Built around a roughly 400-mile pipeline constructed by TransCanada, the project overcame rugged terrain and significant cost escalation. Fulford noted that budgeted construction costs for the Coastal GasLink pipeline ballooned from CAD $6 billion to CAD $16.4 billion, with overruns absorbed primarily by TransCanada and project sponsor Shell. Despite the escalation, the project reached final investment decision (FID) and has since begun operations.

Canada’s success hinged on a carefully negotiated fiscal environment that provided long-term predictability. The federal government granted “Nation Building Status,” signaling that the project’s tax and regulatory framework would remain stable. British Columbia mitigated front-loaded taxes, reduced corporate income tax rates from 12% to 9% through credits, and introduced accelerated depreciation to defer tax burdens. A capped carbon tax was also locked in, offering investors certainty absent in Alaska, which has no carbon tax. Property taxes in Canada remained far lower than Alaska’s typical rates.

Fulford stressed the importance of such stability: “Ultimately what we are talking about is a fiscal framework and a government tax regime that an investor or lender can depend on in the long-term.”

The project’s financing relied entirely on private equity and parent-company balance sheets. Equity partners—including Shell, Petronas, and others—entered take-or-pay marketing arrangements covering 100% of their entitlements, transferring credit risk to highly rated corporate entities and securing low-cost debt. No direct government capital or guarantees were provided, unlike earlier Alaska proposals that envisioned significant state involvement.

Alaska’s current proposal, led by Glenfarne, diverges from the 2014 Senate Bill 138 framework. That earlier plan assumed state equity participation, profit-sharing mechanisms, and a pipeline primarily serving Southcentral Alaska power needs before export. Glenfarne’s structure emphasizes private development, with gas supplied from the North Slope and export focused on Asian markets. Fulford told senators the shift in profit allocation between upstream production and downstream liquefaction/export would require a fresh look at state taxation and revenue models. He noted that Wood Mackenzie’s analysis of the project appeared consistent with state assumptions, but recommended revisiting legislative direction to align incentives.

Duncan assessed Glenfarne’s progress as falling between decision gate 2 (concept selection) and decision gate 3 (pre-FEED), with FID typically occurring at gate 4 once Class 3 cost estimates solidify. He acknowledged Glenfarne’s public actions—securing construction resources, preliminary gas supply agreements, and permitting advancements—as reasonable momentum-building steps. “There does seem to be an assumption that the project will go ahead,” Duncan said. “I haven’t seen anything I would consider to be inappropriate.”

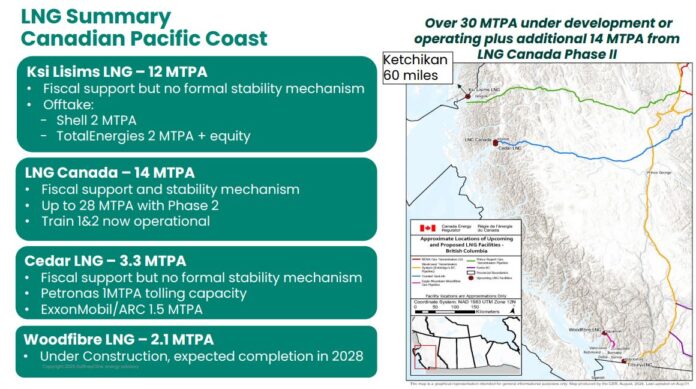

The global LNG market provides context for Alaska’s renewed interest. Current capacity stands at approximately 400 million tonnes per annum (MTPA), with projections targeting 700–800 MTPA by the early 2030s, driven largely by Asian demand. Pacific Coast projects benefit from low-cost feed gas and shorter shipping routes to premium markets. Fulford cited Petronas’s sale of a 5% stake in LNG Canada as an example of how equity can be monetized without perpetual state ownership.

Committee members pressed on disclosure, comparing Canada’s five-year fiscal negotiations with Glenfarne’s more opaque progress. They also explored whether tax breaks were needed for production, pipeline construction, or export operations, and whether the project’s evolution warrants new legislation. Fulford acknowledged that LNG Canada’s developers had insisted on tax changes to make the projects investable, breaking a years-long impasse.

Alaska’s project faces unique challenges, including higher property taxes and a history of stalled efforts dating back decades. Yet proponents argue low-cost North Slope gas and strategic location could compete effectively if fiscal terms attract investment. The committee’s discussion signals lawmakers are weighing whether to update statutes or maintain flexibility as Glenfarne advances toward potential groundbreaking.

No formal recommendations emerged from the hearing, but the testimony underscored that predictable, investor-friendly policies were key to Canada’s success. Alaska’s path forward may hinge on similar adaptations.