By TIM BARTO

I was on a conference call yesterday when my cell phone lit up. It was Frankie, a baseball buddy; a guy I coached when he was in Little League and I was just 19, and then again when he was in high school and I was fresh out of college. I couldn’t take Frankie’s call, but I quickly figured out why he dialed, as my phone started beeping non-stop with friends and family sending cryptic texts saying, “RIP Pete Rose”.

Peter Edward Rose, the man who played more games, had more at-bats, and accumulated more base hits than anyone who ever played Major League Baseball, died today. He was a legendary ballplayer and, very unfortunately, one of the most controversial figures in the annals of the game.

He loved everything about the game and could possibly have been the first unanimous selection to the Hall of Fame had he not, in the words of former Commissioner Bart Giamatti, “engaged in a variety of acts that have stained the game.”

But that’s enough of the ugly stuff.

Pete Rose was one of my childhood heroes. He was captain of my favorite team, the Cincinnati Reds. Those Reds’ teams of the 1970s – known as the Big Red Machine – had had an average season win percentage of .595, won five division titles, four National League pennants, and two World Series championships. Pete was Rookie of the Year in 1963, League MVP in 1973, and a three time batting champion, along with countless other achievements.

While Pete Rose loved statistics like those, it was the manner in which he approached his craft that made fans of us who grew up watching baseball in the 1960s and 70s. Pete played baseball the way it was meant to be played.

He drove roommates crazy because he woke up early in the morning to take 100 practice swings in his hotel room from each side of the plate (he was a switch hitter). He talked baseball non-stop, often to the annoyance of those sitting near him on cross-country plane flights.

During one memorable flight, Pete was sitting next to another player when they began experiencing terrible turbulence, causing the airplane to pitch and yaw, and the other player’s knuckles to turn white as he imagined the worst. Pete noticed the terror on the young man’s face and comforted him in a very Pete Rose manner, that went something like this . . .

“I think we’re going down,” Pete told him. “We’re all gonna’ die in a fiery explosion.” Seeing that the kid was scared and knowing, even worse, that he was struggling with the bat lately, a smiling Rose quipped, “But at least I’ll go down knowing I have a .300 lifetime batting average. What’re you hitting?”

Such was the never ceasing, always competitive attitude of Charlie Hustle, as he became known, the moniker courtesy (as baseball legend has it) of Yankee greats Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford. The irony is that Mickey and Whitey were using it derogatorily, mocking the brash young rookie’s over-efforting, while Rose took it as a compliment and literally ran with it. He sprinted to first base when he drew a walk, and he sprinted around the bases on the rare occasion that he hit one out of the park.

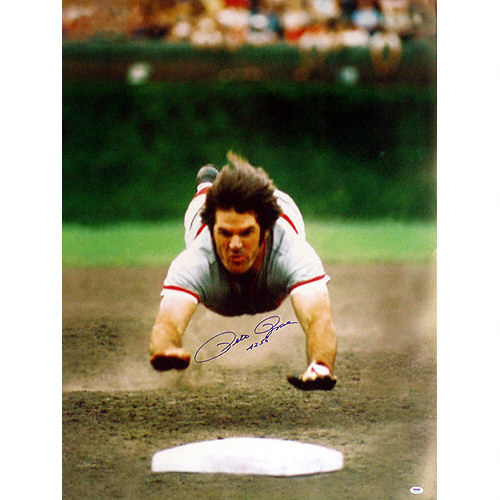

Charlie Hustle slid headfirst into bases, prompting millions of us kids to do the same . . . much to the horror of our mothers and damage to our fingers and forearms. We had dirt all over the fronts of our uniforms, a sign that we played the game the Pete Rose way, the way our fathers taught us to admire. Run hard, play to win, always do your absolute best, and be a loyal teammate.

I even crouched low in my batting stance because that’s how Pete Rose stood at the plate. I had some good seasons and some really bad seasons, but was good enough to make all my high school baseball teams. Unfortunately, the worse I batted, the lower I would crouch until I was curled up in a fetal position that took so long to uncoil from that the catcher was already throwing the ball to the pitcher when I was still finishing my swing.

Coach Grover knew how much I loved baseball and how much I was pressing because I wasn’t hitting. So, one practice during my sophomore season, while taking batting practice from a stance that resembled a slumbering rattlesnake more than a fearsome hitter, Coach Grover asked me why I was crouched down so low. Realizing the question wasn’t meant to be a compliment, and feeling rather embarrassed that I was doing it only to be like Pete Rose, I blushed, avoided eye contact, and didn’t say anything. Coach knew I was a Reds fan, so he just smiled and nodded. “That’s what I thought,” he said. “Try standing up and let’s see if we can quicken your swing and let you see the ball better.”

My batting average rose a hundred points over the next couple games, and while I may have straightened my stance, I didn’t give up running out a walk or sliding headfirst. Pete Rose never gave up playing hard or loving the game.

During game six of the 1975 World Series – arguably the best baseball game of all time – Pete came to bat late in the game as the clock neared midnight. “Isn’t this some kind of game?” he asked Red Sox catcher Carlton Fisk. After the Red Sox won that contest on Fisk’s dramatic 12th inning home run, forcing a seventh and decisive game, Pete was so overwhelmed by the excitement and enormity of the game that he couldn’t stop talking about it, even after the Reds boarded their team bus in the wee hours of the morning to head back to their hotel.

Manager Sparky Anderson had enough already. He knew he wouldn’t be able to sleep after watching his team blow a late-inning lead and a chance to win the championship that had so frustratingly eluded his vaunted 108-win ballclub, and he essentially told his team captain to put a cork in it, adding something along the lines of “Big Red Machine my ass.” Pete guaranteed his skipper that they would win game seven and the championship. They did, and Pete was voted MVP of the Series.

After the 1978 season, which saw Rose hit safely in 44 consecutive games (second only to Joe DiMaggio’s 56 game streak), the inconceivable occurred as Pete and the Reds parted company with Rose opting to test the rather new free agent market and become the highest paid player in the game by signing with the Philadelphia Phillies.

This treachery was made all the worse because Andy, one of my very best friends, was a diehard Phillies fan, forcing me to endure references to Pete the Phillie pretty much every time I saw him. (Andy was the sender of one of those texters who sent a text announcing Pete’s passing.)

It was years before I – and many other Reds’ fans – forgave Charlie Hustle for leaving the team and town in which he grew up, but we are a fickle lot when it comes to our baseball idols. It didn’t take long after Pete returned to Cincinnati in 1984, this time as player-manager, that his unforgivable betrayal was rather quickly forgiven. We had to forgive because he loved the game, and he played it with such vigor that it is impossible not to admire him.

The debate over whether Pete’s gambling indiscretions should still be prevent him from being allowed into the Hall of Fame will rage over the next few days, perhaps into the next voting cycle. Perhaps the Hall will do what was done after Roberto Clemente tragically died and make an exception to enshrine him. I wouldn’t bet on it (pun intended), but there is no one from a purely baseball performance point of view that deserves it more.

Tim Barto is vice president of Alaska Family Council, and a lifelong baseball fan. He was involved at every level with the Chugiak-Eagle River Chinooks of the Alaska Baseball League, including president, coach, PA announcer, play-by-play broadcaster, and writer. He will miss Pete Rose and the way Pete Rose played the game.