The Supreme Court on Friday agreed to hear a gun-rights case involving a Texas man who is challenging a federal ban on the possession of firearms by those who are subject to domestic violence restraining orders.

The Biden Administration appealed the case, called United States v. Rahimi, after a federal appeals court invalidated the ban earlier this year.

Zackey Rahimi assaulted his ex-girlfriend in a Texas parking lot in 2019 and warned her that he would shoot her if she said anything about it to anyone. She did say something.

In February of 2020 a Texas state court issued a domestic violence restraining order against Rahimi, which by default prevented him from possessing firearms. He was warned by the judge that violating the order would be a federal felony.

Rahimi is not a sympathetic plaintiff in this constitutional case and was not exactly a responsible gun owner. He was a danger to the public and those closest to him. After the restraining order in February of 2020, he was involved in five known shootings. He also violated the restraint order by going to his ex-girlfriend’s house in the middle of the night.

“Zackey Rahimi was involved in five shootings in and around Arlington, Texas, between December 2020 and January 2021, including shooting into the residence of an individual to whom he had sold narcotics; shooting at another driver after a wreck, fleeing, returning in a different vehicle, and shooting again at the other driver’s car; shooting at a constable’s car; and shooting into the air after his friend’s credit card was declined at Whataburger (I am not making that last one up). Arlington police identified Rahimi as a suspect in the shootings and executed a warrant on his home, where they found a rifle and a pistol. Rahimi was at that time under a Texas state court civil protective order for an allegation of assault family violence, the terms of which expressly prohibited him from the possession of a firearm, which is (or was) a federal crime,” writes the Texas District and County Attorneys Association.

When the police executed a search warrant at his home, they found a handgun, a rifle, ammunition, and a copy of the restraining order. Rahimi, who was also a known drug dealer, peddling marijuna and occasionally cocaine. He was subsequently charged with violating the federal ban on firearm possession by individuals subject to domestic violence restraining orders.

He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to over six years in prison, and three years of supervised parole. Then he challenged the constitutionality of the ban on his ability to own or possess a firearm.

At first, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Rahimi’s conviction. But in 2022, the Supreme Court struck down a decision in New York State relating to the state’s handgun-licensing laws. That is when the 5th Circuit decided Rahimi retained his Second Amendment right to bear arms, because federal government did not demonstrate that the ban aligned with the historical tradition of firearm regulation decided in the New York case.

“The Government fails to demonstrate that § 922(g)(8) ‘s restriction of the Second Amendment right fits within our Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation. The Government’s proffered analogues falter under one or both of the metrics the Supreme Court articulated in Bruen as the baseline for measuring ‘relevantly similar’ analogues: ‘how and why the regulations burden a law-abiding citizen’s right to armed self-defense,’” Judge Cory T. Wilson wrote in United States v. Rahimi. “As a result, § 922(g)(8) falls outside the class of firearm regulations countenanced by the Second Amendment.”

“…the early ‘going armed’ laws that led to weapons forfeiture are not relevantly similar to § 922(g)(8). First, those laws only disarmed an offender after criminal proceedings and conviction. By contrast, § 922(g)(8) disarms people who have merely been civilly adjudicated to be a threat to another person. Moreover, the ‘going armed’ laws, like the ‘dangerousness’ laws discussed above, appear to have been aimed at curbing terroristic or riotous behavior, i.e., disarming those who had been adjudicated to be a threat to society generally, rather than to identified individuals,” Wilson wrote.

Even surety laws, requiring the posting of a bond by the offender, did not quite fit the case, the court said.

“The surety laws required only a civil proceeding, not a criminal conviction. The ‘credible threat’ finding required to trigger § 922(g)(8) ‘s prohibition on possession of weapons echoes the showing that was required to justify posting of surety to avoid forfeiture. But that is where the analogy breaks down: As the Government acknowledges, historical surety laws did not prohibit public carry, much less possession of weapons, so long as the offender posted surety.”

The 5th Circuit said that the prohibition against gun possession, simply because of a domestic violence restraining order, is inconsistent with the New York case (Heller, Bruen) and the Second Amendment; and that it treats the Second Amendment differently than other individual rights that are guarantees. In addition, the federal law has no limiting principles.

The Biden administration petitioned the Supreme Court for a review. U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar noted that disarming individuals who pose a threat to others has long been a government practice and that that allowing the 5th Circuit’s decision to stand will have severe consequences for domestic violence victims.

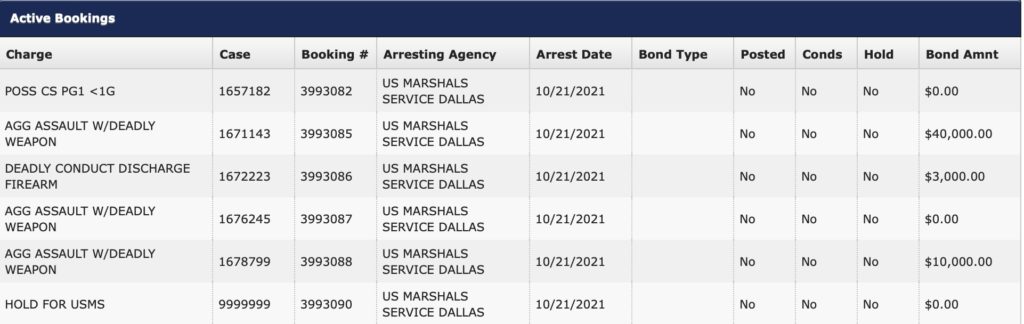

Meanwhile, Rahimi is in jail on other charges relating to his instances of bad behavior with a gun.