By ALEXANDER DOLITSKY

Cross–cultural communication requires a knowledge of how culturally different people groups communicate with each other. Studying other languages helps us understand what people and societies have in common, and it has profound implications in developing a critical awareness of social relationships. Indeed, understanding these relationships and the way other cultures function is the groundwork of successful business, foreign affairs, and interpersonal relationships.

Elements of language are culturally relevant and should be considered. There are, however, several challenges that come with language socialization. Sometimes people can over-generalize or label cultures with stereotypical and subjective characterizations. For instance, one may stereotype by saying that Americans eat hamburgers and French fries in the McDonald’s restaurant daily, and Russians eat borshch (beet and cabbage soup) for breakfast and drink vodka before bedtime. Both stereotypes are far from the truth.

With increasing international trade and travels, it is unavoidable that different cultures will meet, conflict, cooperate and blend together. People from different cultures often find it difficult to communicate, not only due to language barriers but also because of different culture, styles, customs, and traditions. These differences contribute to some of the biggest challenges of effective cross–cultural communication.

Cultures provide people with ways of thinking, seeing, hearing, behaving, understanding and interpreting the world. Thus, the same words or gestures can mean very different things to people from different cultures—even when they speak the same language (e.g., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, England, South Africa and the United States).

The quote “Two nations divided by a common language,” often attributed to George Bernard Shaw, highlights the differences in vocabulary, pronunciation, and cultural nuances that can exist between speakers of the same language. When languages are different, however, and translation is needed just to communicate, the potential for misunderstandings significantly increases.

From the mid–1980s to early–2000s, I was an unofficial Russian translator in Alaska for the US and State of Alaska governments, as well as for various public institutions and private individuals. The most challenging aspect of the translation was relaying specific terminology, such as that used by the US Coast Guard, medical professionals, political protocols and verbiage and, especially, jokes and humorous expressions. Often, I had to provide cultural and historic backgrounds before translating a joke.

Ones, a member of the Russian delegation, in an informal setting over dinner, told a joke to his Alaskan counterparts:

“Archaeologists found an ancient sarcophagus in Egypt with human–made artifacts and skeletal remains. Experts around the world thoroughly investigated this finding to identify the person buried in the sarcophagus but had no success. So, they invited a KGB agent (Soviet Committee for State Security) Major Ivan Ivanov to investigate this matter. Major Ivanov spent nearly three hours in solitude with the skeleton and, finally, with a confidence in his voice, reported to the archaeologists that the remains and skeleton belong to the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses the Second. Archaeologists were impressed by this quick revelation and asked Ivanov, “How certain are you of this remarkable conclusion?” Then Ivanov replied with a great pride, ‘After three hours of the bulldozer interrogation, the skeleton itself revealed to me his identity!’”

The Russian jokester was a large, broad-shouldered man, his voice deep and curt. No one among the Alaskan delegation laughed after hearing the joke. They sat still at the table, holding crystal shots of vodka, and just stared with alarm at the joke-teller.

I had to provide the Alaskans with some background about the notorious brutality of the Soviet KGB. Unfortunately, in the process of explaining the joke, the humor disappeared.

In teaching Russian language at the University of Alaska Southeast for 16 years, my very first message to students was to emphasize that a language must always be understood and learned in a cultural context. As an example, I shared with them a personal and rather humorous story of my early arrival to the United States in Philadelphia during the winter of 1978.

In the early years of my immigration, I watched a lot of TV to learn English, American traditions and lifestyles. Many advertisements described food items and dishes, including various salads, using the word “delicious.”

It was a new experience for me because there were no TV ads for commercial products in the former Soviet Union due to a lack of commercial competition. The government controlled standardized prices for commercial products throughout the entire country.

So, I understood the word “delicious” as a name of the salad (a noun) rather than the quality of the salad (an adjective). In fact, food dishes have a particular name in Russia — Chicken Kiev, Salad Stolichniy (salad capital), Borshch (beet and cabbage soup), Beef Stroganoff (meat stew), Blini (Russian for pancakes), etc.

Later that year, my uncle from Canada, accompanied by his wife and daughter, visited me in Philadelphia. As a welcome greeting to America, they invited me to a fancy restaurant downtown. When the waiter asked for my order, I requested a steak, shot of vodka and “delicious” salad, hoping my order would match the “delicious” salad that I had seen on TV.

The puzzled waiter leaned slightly and whispered to me, “Sir, all our food is delicious.” Then, I clarified to the waiter, “I want a delicious salad.” The confused waiter served me a cabbage with mustard.

So, that evening in the fancy restaurant, I enjoyed a delicious steak and stuffed myself with a cut-in-half cabbage with mustard. This was a prime lesson in cross-cultural miscommunication.

Indeed, the demographics and cultural complexity of our nation changes rapidly. It is only a matter of time before ethnic minorities in our country take a lead in shaping the cultural and ethnic landscape of our nation and, eventually, become a significant ethnic majority. These demographic and cultural changes are unavoidable. However, our society should learn to make inclusive and, yet, conservative cross–cultural adjustments without undermining the fundamental core of American Judeo–Christian religious, cultural and moral values.

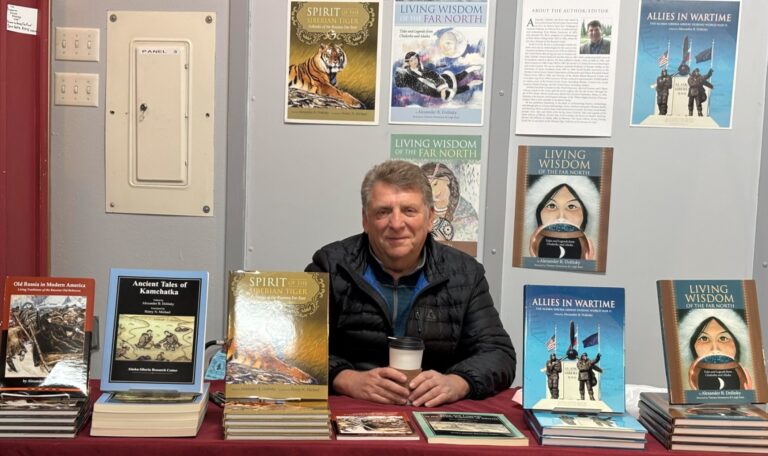

Alexander Dolitsky was born and raised in Kiev in the former Soviet Union. He received an M.A. in history from Kiev Pedagogical Institute, Ukraine in 1976; an M.A. in anthropology and archaeology from Brown University in 1983; and enrolled in the Ph.D. program in anthropology at Bryn Mawr College from 1983 to 1985, where he was also lecturer in the Russian Center. In the USSR, he was a social studies teacher for three years and an archaeologist for five years for the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. In 1978, he settled in the United States. Dolitsky visited Alaska for the first time in 1981, while conducting field research for graduate school at Brown. He then settled first in Sitka in 1985 and then in Juneau in 1986. From 1985 to 1987, he was U.S. Forest Service archaeologist and social scientist. He was an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Russian Studies at the University of Alaska Southeast from 1985 to 1999; Social Studies Instructor at the Alyeska Central School, Alaska Department of Education and Yukon-Koyukuk School District from 1988 to 2006; and Director of the Alaska-Siberia Research Center from 1990 to 2022. From 2006 to 2010, Alexander Dolitsky served as a Delegate of the Russian Federation in the United States for the Russian Compatriots program. He has done 30 field studies in various areas of the former Soviet Union (including Siberia), Central Asia, South America, Eastern Europe and the United States (including Alaska). Dolitsky was a lecturer on the World Discoverer, Spirit of Oceanus, and Clipper Odyssey vessels in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic regions. He was a Project Manager for the WWII Alaska-Siberia Lend Lease Memorial, which was erected in Fairbanks in 2006. Dolitsky has published extensively in the fields of anthropology, history, archaeology and ethnography. His more recent publications include Fairy Tales and Myths of the Bering Strait Chukchi, Ancient Tales of Kamchatka, Tales and Legends of the Yupik Eskimos of Siberia, Old Russia in Modern America: Living Traditions of the Russian Old Believers in Alaska, Allies in Wartime: The Alaska-Siberia Airway During World War II, Spirit of the Siberian Tiger: Folktales of the Russian Far East, Living Wisdom of the Russian Far East: Tales and Legends from Chukotka and Alaska, and Pipeline to Russia: The Alaska-Siberia Air Route in World War II.