TRUMP SPECIFICALLY CALLS OUT THIS ITEM IN MAJOR LANDS BILL SIGNING

Legislation signed Tuesday by President Donald Trump will give 2,800 Alaska Native veterans — or their heirs, if the veterans are deceased — an opportunity to get the land allotments they were promised before serving in the Vietnam War.

Watch Sen. Dan Sullivan talk about the Alaska Native veterans’ land promise, how Sen. Ted Stevens and Congressman Don Young had fought hard for it, and why it’s so important to him personally:

The John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act has 120 different bills wrapped up in it, several of which apply to Alaska, including a bill that would allow an Alaska gasline to run through Denali National Park.

The omnibuslegislation also requires agencies to maintain more open access to federal land, with an “open unless closed” policy, and allows for construction of more target ranges on Forest Service or BLM lands.

The Alaska delegation was on hand for the signing at the White House of the bill that had been introduced by Sen. Lisa Murkowski and Sen. Maria Cantwell of Washington state, who is the ranking Democrat on the Senate Resources Committee that is chaired by Murkowski.

The package was negotiated with the chairman and ranking member of the House Committee on Natural Resources last year, and the vast majority of bills within it have undergone extensive public review in the House, the Senate, or both.

S. 47 contains provisions sponsored by 50 Senators and cosponsored by nearly 90 Senators in the 115th Congress. The bill includes the following provisions of interest to Alaskans:

- Denali Improvement Act – Provides routing flexibility for the Alaska gasline project in Denali National Park and Preserve.

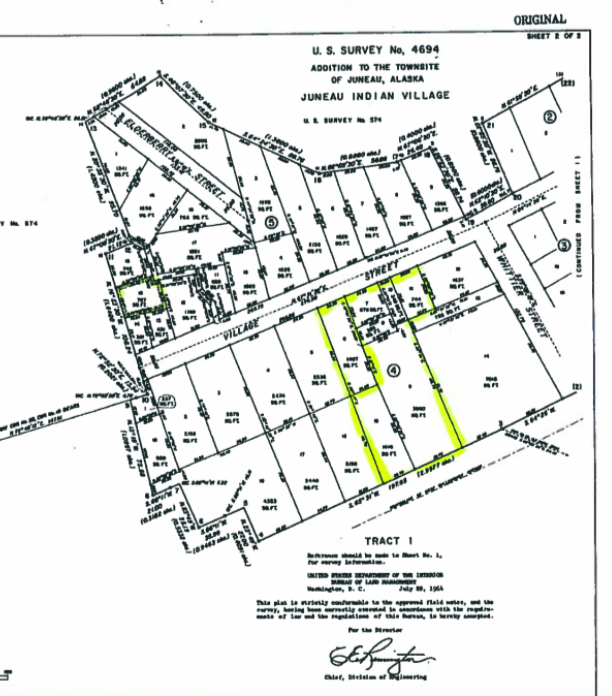

- Alaska Native Veterans Land Allotment Equity Act – Introduced by Sen. Dan Sullivan, R-Alaska, to ensure the federal government fulfills its decades-old promise to provide allotments to Alaska Natives who served in the Vietnam War.

- National Volcano Early Warning and Monitoring Act – Improves the nation’s volcano-related capabilities to help keep communities and travelers safe.

- Sportsmen’s Act – Requires federal agencies to expand and enhance sportsmen’s opportunities on federal lands; makes “open unless closed” the standard for Forest Service and BLM lands; facilitates the construction and expansion of public target ranges, including ranges on Forest Service and BLM lands; and clarifies procedures for commercial filming on federal lands.

- Small Miner Relief Act – Provides relief to four Alaska miners who lost long standing claims due to administrative errors or oversight.

- Kake Timber Parity Act – Repeals a statutory ban preventing the export of unprocessed logs harvested from lands conveyed to the Kake Tribal Corporation.

- Ukpeagvik Land Conveyance – Requires the Department of the Interior to convey all right, title, and interest in the sand and gravel resources within and contiguous to the Barrow Gas Field to the Ukpeagvik Iñupiat Corporation.

- Chugach Land Study Act – Requires the Department of the Interior and the U.S. Forest Service to conduct a study to identify the effects that federal land acquisitions have had on Chugach Alaska Corporation’s ability to develop its lands, and to identify options for a possible land exchange with the corporation.

- National Geologic Mapping Act Reauthorization Act – Renews this program, which is run by the U.S. Geological Survey, for five years.

- Land and Water Conservation – Permanently reauthorizes the Land and Water Conservation Fund, with key reforms to strengthen and provide parity for its state-side program.

More information on S. 47 is available here.