By ALEXANDER DOLITSKY

Updated: Why West provoked and prolongs Russia-Ukraine war?

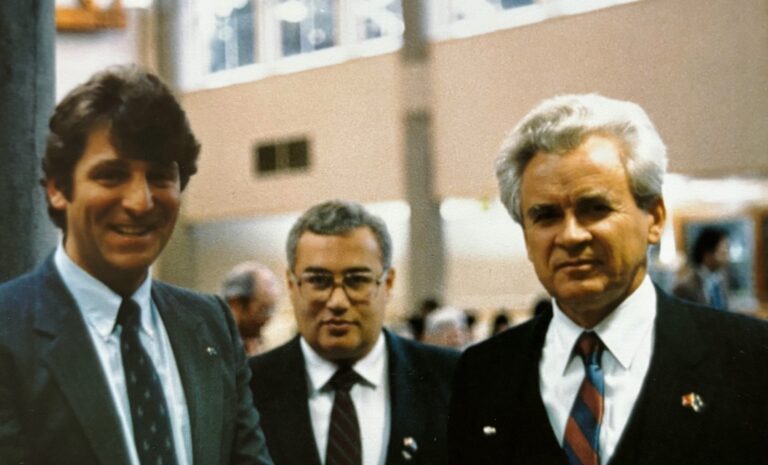

Thirty-five years ago, this spring, Mikhail Gorbachev, then President of the Soviet Socialist Republic, was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Humanities from the University of Alaska Southeast. Then-UAS Chancellor Marshall Lind invited Soviet Ambassador Yuri Dubinin to accept this award on Gorbachev’s behalf.

Dubinin arrived at Juneau with an entourage of six Soviet officials. Back then, I taught Russian Studies and archaeology at UAS and was assigned to accompany the delegation. In fact, Dubinin was the first Soviet ambassador to visit Alaska, post-World War II.

Dubinin was the Soviet ambassador to the United States during much of the turbulent 1980s’ perestroika period. In a Washington post piece, he described himself as a “popularizer of perestroika”—the radical reform efforts of Gorbachev. Dubinin also oversaw opening the Russian embassy to news conferences under Gorbachev’s initiatives.

In Alaska, the mid-1980s through 1990s and early 2000s was an enthusiastic period of the Soviet/Russian–Alaska relationships in nearly all cultural, educational and governmental spheres. I was a busy person, translating, almost daily, for all involved in the Russian-Alaska affairs; the enrollment in my Russian language classes at UAS was over the limit, with a long waiting list. Indeed, it was a promising hope to end Cold War tensions and begin a new era of mutually productive and friendly relationship between two great nations.

Nevertheless, whether under Soviet/Russian leadership of Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Chernenko, Andropov, Gorbachev, Yeltsin or Putin, the U.S. and West never stopped its Cold War policies of undermining USSR/Russia. In the late 1970s, President Jimmy Carter provided military and logistical support to the Afghan Mujahideen, the precursor to the Taliban, thereby provoking Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979.

In fact, every successive U.S. president continued covert and overt interference in countries on Russia’s southern borders, including former Soviet Central Asian republics of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kirgizstan, Tadzhikistan and Turkmenistan, and Georgia and Ukraine.

The ideological architect of the strategy to contain the Soviet Union during Carter presidency was Zbigniew Brzezinski—the U.S. national security advisor and antagonist of the Soviet regime. Indeed, Ukraine played a pivotal role in the so-called Brzezinski Doctrine, which identifies the country as key to preventing Russian–European economic and political integration. Still today, the U.S. foreign establishment is rife with Brzezinski proteges and anti-Russian Cold War ideology.

With Ukraine, because of Brzezinski’s anti-Russian ideology, the West made a major strategic bet that eventually failed. The crippling sanctions against Russia since 2014 were expected to crater the Russian economy, resulting in a popular uprising and leading to the replacement of Vladimir Putin with a pro-Western leader. The hope was that this wishful dream would lead to a pro-Western globalist taking control of the Kremlin, resulting in a boon for Wall Street, as Russia is the richest country in the world in terms of natural resources.

With the growing demand for natural resources, Russia represents a rich investment opportunity in the unforeseen future. However, these Western sanctions against Russia completely failed. In 2024, European Union’s GDP grew 1.7%, while Russia’s grew 4.2%.

Soon after the dissolution of the Soviet Union—as early as 1993—President Bill Clinton started pushing for NATO expansion in Europe, including Ukraine, to which many strategically thinking American sociologists and historians strongly objected. This is how the slippery road to the current crisis might escalate into potential nuclear conflicts.

After gaining its independence in 1991, Ukraine could expect a bright future. At that time, Ukraine (with exception of Russia) was the largest country (territory) in Europe, with a population of nearly 52 million citizens, and sixth largest GDP in Europe. Today, Ukraine population is under 30 million citizens with lowest GDP per capita in Europe (per capita GNI of US$3,540).

Having vital industrial and agricultural sectors, a favorable climate, and fertile land, the country needed effective anti-corruption reforms, a certain level of autonomy for its regions with large Russian ethnic populations, and, most importantly, neutral status with no membership in any military blocs to become one of the most prosperous European states within its 1991 borders.

Instead, billions of dollars from the U.S., Canada, other Western countries, and George Soros poured into Ukraine—not to boost its economy but to reformat public opinion, which overwhelmingly favored neutral status and opposed joining NATO. This influence from the West helped to instigate the “Orange” revolution regime change in 2004, and then “Maidan” in 2014, which was directly coordinated by then-Vice President Joe Biden with Victoria Nuland from the White House in the Ukrainian capital Kyiv.

The new Ukrainian government, selected by Washington and the West, immediately declared its intention to join NATO. In fact, if not for this 2014 coup, there would be no annexation of the Crimean Peninsula by Russia in 2014, no war today in East Ukraine, and no risk of potential nuclear World War III.

In short, the U.S. and Western policies of using Ukrainians as cannon fodder to inflict a strategic defeat on Russia denigrates and contradicts the fundamental spirit and soul of America itself. While claiming to adhere to Western/Judeo-Christian values, the U.S. and European Union provoked and continues to fund a prolonged war between two nations that have lived together for over three centuries and are bound together by close historical, linguistic, religious, economic, cultural, and family ties.

No one can predict how the Russian-Ukrainian/West conflict will end; but one thing is certain that the Russian government and people do not take ultimatums very well. Recent pledges and demands of the European Union to accelerate and increase military assistance to Ukraine will only prolong this war. Indeed, as drums of World War III keep banging, those who are not among decision-makers or on the battlefields should, at least, try to clear the smog of this war.

Alexander Dolitsky was born and raised in Kiev in the former Soviet Union. He received an M.A. in history from Kiev Pedagogical Institute, Ukraine in 1976; an M.A. in anthropology and archaeology from Brown University in 1983; and enrolled in the Ph.D. program in anthropology at Bryn Mawr College from 1983 to 1985, where he was also lecturer in the Russian Center. In the USSR, he was a social studies teacher for three years and an archaeologist for five years for the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. In 1978, he settled in the United States. Dolitsky visited Alaska for the first time in 1981, while conducting field research for graduate school at Brown. He then settled first in Sitka in 1985 and then in Juneau in 1986. From 1985 to 1987, he was U.S. Forest Service archaeologist and social scientist. He was an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Russian Studies at the University of Alaska Southeast from 1985 to 1999; Social Studies Instructor at the Alyeska Central School, Alaska Department of Education and Yukon-Koyukuk School District from 1988 to 2006; and Director of the Alaska-Siberia Research Center from 1990 to 2022. From 2006 to 2010, Alexander Dolitsky served as a Delegate of the Russian Federation in the United States for the Russian Compatriots program. He has done 30 field studies in various areas of the former Soviet Union (including Siberia), Central Asia, South America, Eastern Europe and the United States (including Alaska). Dolitsky was a lecturer on the World Discoverer, Spirit of Oceanus, and Clipper Odyssey vessels in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic regions. He was a Project Manager for the WWII Alaska-Siberia Lend Lease Memorial, which was erected in Fairbanks in 2006. Dolitsky has published extensively in the fields of anthropology, history, archaeology and ethnography. His more recent publications include Fairy Tales and Myths of the Bering Strait Chukchi, Ancient Tales of Kamchatka, Tales and Legends of the Yupik Eskimos of Siberia, Old Russia in Modern America: Living Traditions of the Russian Old Believers in Alaska, Allies in Wartime: The Alaska-Siberia Airway During World War II, Spirit of the Siberian Tiger: Folktales of the Russian Far East, Living Wisdom of the Russian Far East: Tales and Legends from Chukotka and Alaska, and Pipeline to Russia: The Alaska-Siberia Air Route in World War II.

Alexander Dolitsky: What America can learn from the decline and fall of world empires

Alexander Dolitsky: Proof positive that life experience is an author’s greatest asset