By NIKI TSHIBAKA

In the early 1800s, a modern-day Moses was born to Antebellum America. Like Moses, he was born into slavery and would find freedom by way of a river; like Moses, this child, delivered on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay, would become a deliverer for his people; and, like Moses, his would be a simple message for our nation’s pharaohs: “Let my people go.”

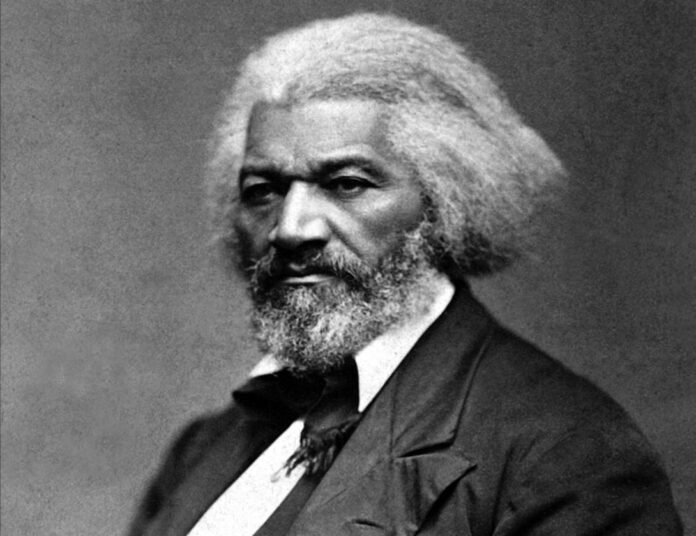

His name was Frederick Douglass.

By all appearances, Douglass was destined for a life of servitude and suffering. But he resolved that the institution of slavery would not determine his destiny. As a young man, he escaped to freedom by taking a steamboat up the Delaware River to Philadelphia. In time, he rose to heights most African Americans of his generation thought impossible. A self-educated man, he became a prolific writer and published his own antislavery newspaper, The North Star.

He also became an advisor to President Abraham Lincoln and the first African American confirmed by the U.S. Senate for a presidential appointment. Most importantly, Douglass became one of the greatest abolitionist voices in American history, convicting America’s conscience with his blistering rebukes of its hypocrisy in tolerating slavery.

“The existence of slavery in this country brands your republicanism as a sham, your humanity as a base pretense, and your Christianity as a lie,” he roared.

Douglass’ advocacy was grounded in propositional truths, imbuing his arguments with an enduring relevance that speaks powerfully to our ongoing national dialogue on race, justice and equality. For example, while he fervently opposed racism, Douglass also decried what he perceived as the benevolent bigotry of White abolitionists. Racism was dehumanizing, an assault on the inherent dignity of Black Americans. The recurrent, overweening generosity of his abolitionist allies and the employment of their power and privilege to artificially uplift Black people, however, also were demeaning and destructive to Black Americans.

Douglass was a principled purist in his pursuit of equality. He believed a sincere commitment to righting the wrongs of slavery required equal treatment, not special treatment, for Black people. Equality, in any meaningful and lasting sense, would be achieved only through justice, not generosity.

Our Declaration of Independence had masterfully established the propositional truth that justice was rooted in the unchanging laws of nature and nature’s God. Conversely, White America’s generosity, and its episodic abdications of privilege, were subject to the ever-fickle vicissitudes of human will. White paternalism would not carve a path to racial equality. Instead, it would calcify existing societal structures of racial inequality, resulting in slavery by another name and further entrenching Black dependence on White America.

If Black Americans wanted to stand beside White Americans as true equals, it had to be on their own feet and by their own merit; as Douglass put it, without “prop[ping] up the Negro.” Anything less would create only a chimera of equality:

What I ask for the Negro is not benevolence, not pity, not sympathy, but simply justice. The American people have always been anxious to know what they shall do with us. . . . Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us. . . . If the apples will not remain on the tree of their own strength, . . . let them fall! I am not for tying or fastening them on the tree in any way, except by nature’s plan, and if they will not stay there, let them fall. And if the Negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall also. All I ask is, give him a chance to stand on his own legs! Let him alone! . . . Let him fall if he cannot stand alone!

Despite his criticisms of America, Douglass labored to reform our nation, not remake it – to incarnate its founding ideals, not uproot them. He advocated for the guarantee of certain inalienable rights, not for the promise of certain inalienable outcomes. He had great faith our nation one day would make the full measure of freedom’s blessings the birthright of every American.

Like Moses, Douglass would not live to see the fulfillment of his vision for our nation. But he would help lead us to the river’s edge of that Promised Land, believing his life and hopes were a prophetic glimpse of what was to come.

As I write this article, I am particularly inspired by the words Douglass spoke in a lecture to some Black students: “What was possible for me is possible for you.” Today, it is a message of encouragement for Americans of every race, color, and creed. Douglass stands astride history with that stirring reminder for us all:

What was possible for me is possible for you.

There is reason for hope.

Niki Tshibaka is a former federal civil rights attorney and government executive.