By MICHAEL TAVOLIERO

The Alaska Legislature’s passage of House Bill 57 reflects a familiar but flawed approach to educational improvement: raise the Base Student Allocation and add targeted programs without confronting the systemic inefficiencies that undermine return on investment.

While the bill addresses class-size caps, reading incentives, and charter school processes, the FY 2024 audited revenue data (found under “Annual Revenue 2024” link at https://education.alaska.gov/schoolfinance/budgetsactual) show that Alaska’s education system is not uniformly underfunded. The real challenge is uneven spending patterns, weak accountability, and the absence of performance-linked incentives.

Evidence from FY 2024 Revenues

For major municipal districts, per-pupil operating revenue is already substantial:

- Anchorage: $16,662 per ADM at 42,764 Total enrollment (average daily membership, or ADM)

- Fairbanks: $17,757 per ADM at 12,452 Total ADM

- Kenai Peninsula: $19,778 per ADM at 8,301 Total ADM

These figures represent almost 50% of the state’s ADM and 41.22% of all state education revenue drawn from local, state, and federal sources. These are comparable to or higher than many high-performing U.S. districts. Yet outcome disparities persist, and past BSA increases have not translated into proportional gains in student achievement.

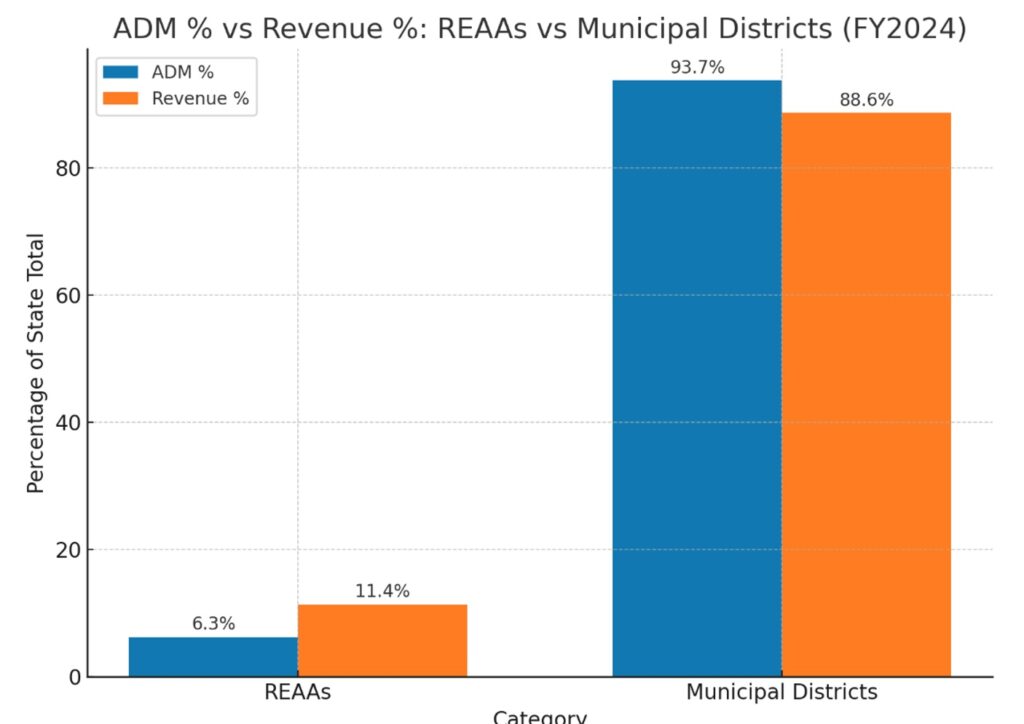

For REAAs, which account for 6.27% of total ADM and 11.39% of total education revenue, per-ADM figures vary widely: small, remote systems can exceed $100,000 per student due to scale penalties and high-cost federal programs; others are closer to urban levels. Unlike municipal districts, REAAs have no local tax base, relying almost entirely on state and federal funding plus Special Revenue Funds.

Why HB 57’s Approach Is Misaligned

While HB 57 creates a “Task Force on Education Funding”, it leans heavily on traditional inputs:

- Increased BSA

- Expanded vocational/technical funding factor

- Reading incentive grants

- Transportation formula changes

What it does not do is link these increases to:

- Teacher contract flexibility

- Outcome-based budgeting

- Accountability for professional development spending

- Innovation pilots in underperforming schools

For municipal districts, this means perpetuating inefficiencies where local revenue could be leveraged for innovation.

For REAAs, this means applying uniform funding increases to non-uniform realities, ignoring scale, remoteness, and staffing constraints.

Paths Forward by Governance Type

1. Negotiate Performance-Linked Incentives (PLIs)

Municipal Districts:

As part of collective bargaining agreements, municipal school districts should tie step increases or stipends to gains in reading/math proficiency, attendance, graduation rates, and reduced remedial coursework. Local tax authority can support targeted incentive funds.

REAAs:

As part of collective bargaining agreements, the Alaska legislature should use school-wide bonuses tied to K–3 reading gains, attendance, and on-time credit accrual. Include hard-to-staff premiums for SPED, STEM, and secondary math, structured as retention bonuses.

2. Develop Innovation Pilots via Memorandum of Understanding

Municipal Districts:

Create “pilot zones” with flexible staffing and compensation models. Test competency-based classrooms or alternative schedules in underperforming schools without full contract renegotiation.

REAAs:

Pilot multi-age competency groups, hybrid teacher/para models, extended-year terms, and community-embedded career and technical education. Use short, renewable MOUs with clear metrics to minimize risk.

3. Incentivize Upskilling of Support Staff

Municipal Districts:

Integrate para-to-teacher pipelines into collective bargaining agreements, focusing on shortage areas. Use local funding to underwrite coursework and credentialing.

REAAs:

Build special education para II/III tiers and offer stipends for lead paraprofessionals. Service-year commitments can stabilize staffing where recruiting externally is costly and slow.

4. Link Professional Development to Outcomes

Municipal Districts:

Require professional development vendors to include pre/post instructional measures, tie renewals to demonstrated student gains, and align training with district goals.

REAAs:

Adopt a “rule of three” for professional development: pre/post measures, in-class coaching, and a 90-day evidence review. Focus on universal screener growth in reading/math.

5. Engage Legislators for Flexibility

Municipal Districts:

Advocate for Public Employment Relations Act (PERA) amendments to allow merit pay pilots and efficiency-linked bargaining exceptions. Seek targeted opt-outs from rigid salary structures.

REAAs:

Request waivers for small-cohort scheduling, tele-service credit for special education, and fast-track approvals for micro-school charters or innovation schools.

Financing the Shift Using FY 2024 Data

Municipal Districts:

Reallocate a portion of professional development budgets to outcome-linked training. Fund incentives from efficiency gains, reduced turnover, and targeted use of local dollars.

REAAs:

Redirect special revenue funds allocations to para-to-teacher pipelines. Use savings from reduced itinerant travel and vacancy churn to underwrite PLIs and retention bonuses.

The Special Revenue Fund Illusion and the False Case for Municipal Property Tax Increases

In FY 2024, municipal school districts, Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Kenai Peninsula, controlled nearly half of the state’s ADM but drew in 38.34% of all state education revenue, before factoring in their substantial local contributions through property taxes and in-kind contributions. Alongside their state and local funds, they also received tens of millions in Special Revenue Funds (SRF):

- Anchorage: $95 million SRF

- Fairbanks: $26 million SRF

- Kenai Peninsula: $23 million SRF

| School District | ADM | Total Revenue ($) | Per ADM Revenue ($) | Local Contribution ($) | Special Revenue Funds ($) |

| Anchorage | 42,764 | 687,656,244 | 16,080 | 221,038,822 | 95,165,535 |

| Fairbanks | 12,452 | 210,732,243 | 16,924 | 55,164,201 | 26,475,110 |

| Kenai Peninsula | 8,301 | 156,904,011 | 18,902 | 54,753,114 | 23,710,637 |

Special revenue funds include restricted-use federal and state categorical grants (Title I, IDEA, Impact Aid, targeted reading and CTE grants) that, while not fully fungible, still offset costs that would otherwise be paid from general operating funds.

Under AS 14.17.410(b)(2), municipalities are already required to make a “required local contribution” based on taxable property value. HB 57 layers additional state funding on top, through a 12 % BSA increase, expanded vocational/technical allocations, reading proficiency incentives, and adjusted transportation subsidies. This inflow arrives without any mandate for offsetting property tax relief or demonstrable efficiency gains.

The result is local governments can claim “budget gaps” that justify tax increases even as per-ADM revenues, when special revenue funds are included, are on par with or above those in high-performing states. Property tax hikes are thus politically framed as necessary to protect educational quality, when in reality:

- Special revenue fund growth reduces the burden on unrestricted local dollars for targeted programs.

- HB 57 injects significant new state revenue without requiring reform.

- Historic revenue increases have failed to deliver proportional academic improvements.

This creates a false justification for property tax increases: voters are told schools are underfunded, when the data show funding has grown substantially, but without performance-linked reforms to ensure the dollars produce better outcomes.

Conclusion

HB 57’s “fund first, reform later” posture risks reinforcing the same inefficiencies that keep Alaska’s achievement stagnant. The FY 2024 data show that both municipal districts and REAAs need incentive-driven, performance-focused reforms, but the levers differ.

For municipal districts, the narrative that property tax hikes are unavoidable is undermined by the fiscal reality:

- Per-ADM revenues are already substantial.

- Special Revenue Funds (SRF): Tens of millions in federal and state categorical grants offset targeted costs that would otherwise be borne by unrestricted local funds.

- HB 57 injects significant new state revenue without requiring any efficiency benchmarks, outcome-based budgeting, or property tax offsets.

The result is a political framing in which voters are told schools are “underfunded” while, in truth, the total revenue picture, including special revenue funds, places Alaska’s major municipal districts at or above the per-pupil funding levels of many high-performing states. This creates a false justification for property tax increases: the call for more local taxation is driven less by genuine fiscal shortfall and more by a policy choice to preserve inefficient structures without demanding measurable results.

For REAAs, the problem is different. They lack a local tax base, rely heavily on volatile state and federal funds, and face structural cost penalties due to remoteness and scale. Uniform Base Student Allocation (BSA) increases are a blunt tool in this context, failing to address chronic staffing shortages, high turnover, and the logistical burdens of service delivery.

In both cases, the path forward is not simply more money, but better alignment of funding with measurable outcomes:

- Performance-linked incentives

- Innovation pilots tailored to local realities

- Professional development tied to demonstrable classroom impact

- Legislative flexibility to escape one-size-fits-all mandates

Only by coupling funding to results, and by rejecting the property tax “necessity” myth where special revenue fund and state increases already close much of the gap, can Alaska ensure that every additional dollar delivers a clear return in student achievement.