In 1998, Must Read Alaska Editor Suzanne Downing, who was editor of the Juneau Empire, and John Winters, then-publisher, led a team of writers, editors, photographers, and designers to document the progress of Alaska Natives and Alaska as a state 25 years after the passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. It was an anniversary project that was a big ambition for what was a small newspaper, with a Sunday circulation of just 9,000.

In 2021 it is still one of the most exhaustive reports on the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, reporting the perspectives of Native Alaskans who were there from the outset of the historic agreement that created Alaska Native corporations, and Alaska as an oil-producing state.

The questions the project sought to answer were: What has been the result of the Alaska Claims Settlement Act? Has the Native corporate structure set up by ANSCA been a success? Have Alaska Natives benefited from ANCSA? How has the creation of Native corporations changed the cultures of Alaska’s Native peoples?

Reporters Cathy Brown, Lori Thomson, and Svend Holst, and photographers Brian Wallace and Michael Penn, combed the state from Atka and Savoonga in the West, Utqiagvik in the north, and Angoon in Southeast, — 37 communities in all — to to document the stories of those who helped with the passage of ANSCA, as well as those Natives impacted by the landmark legislation, and to document their perspectives on its successes and failures.

“In their travels to dozens of towns and villages, reporters talked to hundreds of people from all walks of life, seeking the viewpoints of Natives, anthropologists, economists and historians across the state, along with the opinions of Native corporation executives and everyday shareholders,” Publisher Winters wrote in the introduction to the series.

Other contributors to the project were Jon Holland, Doug Loshbaugh, M. Scott Moon, Tim Bradner, Davida Doherty, Mona Entwife, Kristan Hutchison, James Folker, Cathy Martindale, and Ed Shoenfeld.

The stories are captured in Between Worlds, the special project that was funded by William Morris III, then the owner of the Juneau Empire.

One fraction of the project is printed in part here, with links below to the entire project, which is now housed digitally at the Alaska Humanities Forum in its Alaska history course. Although print copies exist, they are few and far between.

Alaska’s first people stood between Big Oil and a pipeline. They negotiated the best deal they could.

By CATHY BROWN, LORI THOMSON, AND SVEND HOLST

Her first sight of the huge rock filled Lydia George with shock. Then tears.

A Tlingit Indian from the village of Angoon in Southeast Alaska, George was a teacher at the University of Alaska Fairbanks in the 1980s when students showed her a rock as big as a table on display in the library. A Raven design was chiseled on the rock’s face.

During the long fight over Native land claims, George had heard Tlingit elders talk about such rocks, used for hundreds of years as titles to land; it was a type of land claim the government never recognized.

“What is it doing in the library? When the government did not give it recognition, why are they showing it off to tourists?” George said. “I touched it and tears just flowed down my face.”

The rock serves as a painful reminder of the battle Alaska Natives waged for more than 100 years to claim ownership of their land. The fight culminated with the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1971, but began soon after the United States purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867.

Tlingit leaders in Southeast Alaska protested the sale, saying Russians, who established their first permanent Alaska settlement in 1784, couldn’t sell what wasn’t theirs; Natives, after all, had lived on the land for centuries.

They pressed the point in a 1947 lawsuit in the U.S. Court of Claims. As Westerners spread throughout Alaska, other Native groups also at times protested encroachment on their land.

But it was Alaska’s statehood in 1959 that escalated those conflicts to a critical stage.

The statehood act gave Alaska the right to select more than 100 million acres of land as its own to develop. It soon became clear to Alaska Natives that development was going to work against their traditional lifestyle.

Some of the development projects proposed for Alaska threatened Natives’ very existence.

In 1963, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers wanted to build a 530-foot-high dam on the Yukon River to generate electricity. The dam would have put Athabascan villages under water and forced about 1,200 Natives to leave their homes.

The U.S. Atomic Energy Commission planned to set off a nuclear explosion at Cape Thompson to create a harbor for shipping minerals and other goods from northwest Alaska.

The proposal, called Project Chariot, drew national attention to Alaska Natives’ plight and helped prompt establishment in 1962 of the Tundra Times, a newspaper funded in part by Forbes’ magazine’s Malcolm Forbes.

Inupiat Eskimo Howard Rock of nearby Point Hope was outraged that no one considered the danger of radioactive contamination to Natives living there. Rock became editor of the Tundra Times, the first statewide vehicle for Natives to communicate about land claims and other issues.

A year later, the Alaska Federation of Natives was launched, creating the first united front for Natives across the state. Land claims were at the top of its agenda.

Native leaders pressed for a freeze on all land transfers until Native claims had been resolved, a freeze that U.S. Interior Secretary Stewart Udall granted in 1965.

It was a critical victory for Natives. Robert Willard, a Juneau leader in the claims battle, remembers Natives’ reaction: “Everybody said, ‘He did what?’ Then everybody from our side realized this is pretty serious.”

Non-Native homestead applications were stalled and business plans faltered, said Emil Notti, who was the AFN president at the time.

“If it was an Indian problem, we’d still be working on it,” Notti said. “When it became a problem for the state of Alaska, homesteaders, oil companies, cities, it became everybody’s problem.”

The discovery of oil on the North Slope in 1968 sped up the need to resolve land claims, and big oil companies joined the ranks of those trying to gain access to land tied up in Native land claims.

Willard was at the table when the AFN board met with oil company executives developing the trans-Alaska pipeline. He recalled how Joe Upicksoun, an Arctic Slope Native, made clear the Native position:

“Not one drop of oil, not one inch of pipe will come from the Arctic Slope until the Native claims settlement act is settled.”

Oil executives responded that nothing would stop the pipeline. They would take Alaska Natives to court if they had to, but of course that would probably take a hundred years.

“We – can – wait,” Upicksoun said.

Willard’s eyes lit up and a thin smile crossed his heavily creased face as he recalled that moment. Then he said quickly, “Well, Big Oil couldn’t wait 100 years.”

That was the critical turning point when oil companies threw their weight behind the Natives. And it’s why the settlement act passed in 1971 instead of 2010, said Steve Haycox, a University of Alaska history professor.

In 1968, a task force appointed by Gov. Walter Hickel recommended Natives receive title to 40 million acres and 10 percent of oil income from certain lands, among other provisions.

A bill based on those recommendations was introduced in Congress, but died. For the next three years, Congress, Native leaders, oil companies, chambers of commerce, mining interests, sportsmen and others argued over a host of land claim proposals.

The AFN lobbied on a shoestring budget. Villagers held bingo games and raffles to raise cash for the cause, and AFN borrowed money – $100,000 from Natives in Tyonek who sold oil leases on their reservation, and $200,000 from Yakima Indians in Washington, said Don Mitchell, a former attorney for AFN.

Another avenue of funding was the Alaska Rural Affairs Commission, a commission created by Hickel. By then the governor realized he needed to negotiate with AFN and couldn’t do so if Native leaders couldn’t afford to travel to meetings, Mitchell said. They used their gatherings to work on the land issue, although there was just enough money to meet in Anchorage once a year.

“But we could only afford one hotel room,” said John Schaeffer, former president of NANA Regional Corp. “So all 15 of us stayed in one hotel room.”

The land freeze fell into jeopardy when Richard Nixon was elected president in 1968. He replaced Interior Secretary Udall with Alaska’s Hickel, who threatened to lift the freeze. “What Udall can do by executive order I can undo,” Hickel said.

But first he needed to be confirmed. With powerful conservation groups working against him, Hickel needed the support of Natives. They, however, had won the ear of certain senators and refused to endorse Hickel. He finally buckled and promised to extend the land freeze.

By 1971, it was clear there would be a settlement.

Native representatives traveled to and from Washington, D.C. as a number of proposals and settlement bills were debated. They spent days meeting with pipeline contractors, unions, the Sierra Club and others, and knocked on doors of congressmen to keep the land claims issue in front of them.

It was a lot of work for the 43 Native lobbyists.

“That’s when we found out there were 435 congressmen and 100 senators,” Willard said….

John Hope, a Tlingit and Juneau resident involved in land claims, described the years immediately following the land settlement this way:

“It’s like you and I never saw a baseball game in our lives. We’d never seen mitts or bats or baseballs. All of a sudden you were told, “Here’s your mitts. Here’s your bats. Here’s your balls. Tomorrow you play the Yankees.”

More from the series at the Alaska Humanities Forum:

Balancing profit and protection

Cultural assimilation or protection?

Overview of regional native corporations:

Arctic Slope Regional Corp.

NANA Regional Corp.

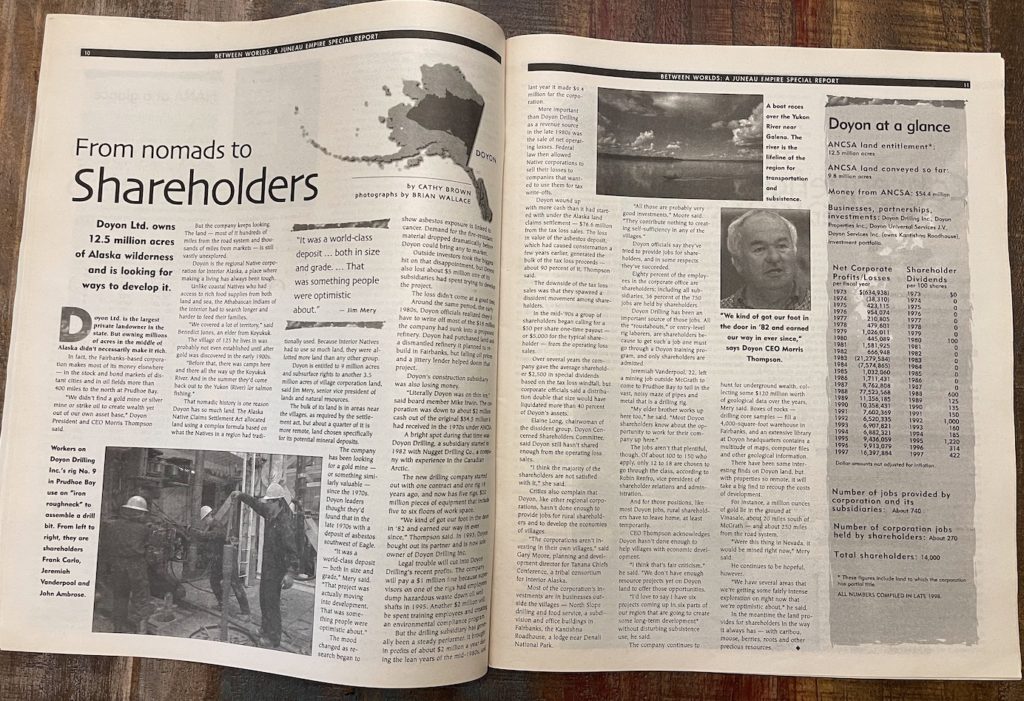

Doyon Ltd.

Bering Straits Native Corp.

Calista Corp.

Cook Inlet Region, Inc.

Ahtna, Inc.

Bristol Bay Native Corp.

Chugach Alaska Corp.

The Aleut Corp.

Koniag, Inc.

Sealaska Corp.

The 13th Regional Corp.

The sales agreement treaty between Russia and the US spelled out clearly in English that the sales agreement did not include transfer of one hundred percent of the lands used and and settled by aboriginal Alaskans from “the sale”. People like Senator Ted Stevens, President Nixon recognized the practical legal problem to be addressed to pull the oil out for the US. The “natives” were under no obligation to negotiate for the sale of the pipeline rights of way. It was pretty darned patriotic of the Natives to give up 3/4’s of their real estate that they didn’t have to do to move into a real estate settlement. Would the Rasmussens or anyone else do this? No.

Who will decide when a Nation fall? What defines your Nation?

My nation is not falling.

“Direct annexation, the acquisition of territory by way of force, was historically recognized as a lawful method for acquiring sovereignty over newly acquired territory before the mid-1700s. By the end of the Napoleonic period, however, invasion and annexation ceased to be recognized by international law and were no longer accepted as a means of territorial acquisition.”

“The title of discovery, would, under the most favorable and most extensive interpretation, exist only as an inchoate title,”

Belated protest had no significance under international law, and that the protracted absence of protest precludes anyone from claiming sovereignty, based on the principle of estoppel.

In the Anglo-Norwegian Fisheries case of 1951, the UK agent argued that governments protest “in order to make it quite clear that they have not acquiesced and to prevent a prescriptive case being built up against them.”

Settlement of Alaska’s Native land claims were based on the Natives having long voiced their relationship to the land, which superseded any claims of Russia’s having delivered title to Alaska to the US.

Thank you for this Suzanne. Yes, it’s time for an updated investigative journalism project on ANCSA. I would love to see high school students statewide take part.

Really enjoying this series of reports, Suzanne. It’s better than taking an Alaska History class from Terrence Cole. And much more honest.

Comments are closed.