By ALEXANDER DOLITSKY

In 1982, I went with a group of graduate students from Brown University to a lecture by the prominent archaeologist Richard Leakey.

Dr. Leakey began his lecture by holding his wallet and then dropping it on the floor in free fall, demonstrating that gravity is an indisputable scientific fact, and archaeological research, on the other side, largely relies on logic and inductive method of analysis—a method of reasoning that involves deriving general principles from a set of observations.

As a student of history and social sciences (anthropology, sociology, archaeology), I, too, found that social sciences data is the most difficult to present in the objective and unbiased way as opposed, for example, to natural sciences.

Social scientists interpret their data based on law-like propositions, subjective views, associative and causal hypotheses (i.e., undefined theories), and influences of the prior well-established intellectual thoughts—generalize experiences, abstract terms, and draw conclusions from assumptions.

In contrast, natural sciences base their inquiries and conclusions on logic and objective natural laws (e.g., gravity, speed of light, magnetism, etc.). Thus, it is imperative to understand sources and components of social science principles prior to applying it to the society at large.

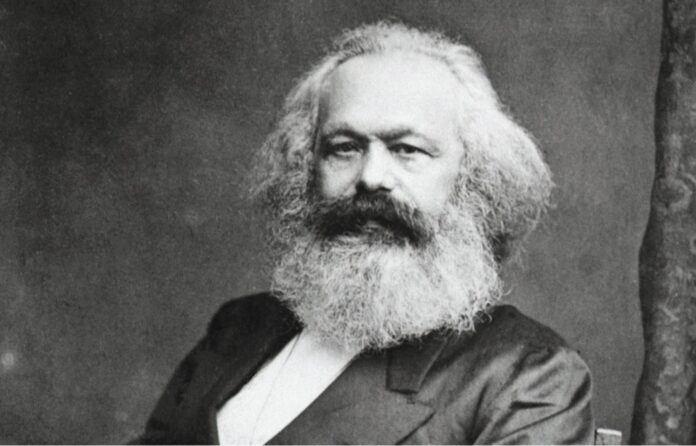

Marxism—the system of views and ideas of Karl Marx—arose because of the study, critical understanding and radical reworking of the advanced ideas of European social and intellectual thought of the 19th century.

The main intellectual sources of Marxism were (1) German classical philosophy, (2) English classical political economy and (3) French utopian socialism in combination with French revolutionary ideas and the practice of European revolutions.

(1) In the process of developing his theory, Karl Marx combined Hegelian dialectics, as a doctrine of development, with Feuerbach’s materialism and for the first time applied the method of materialistic dialectics developed by him to the analysis of the development of human society. The materialistic understanding of history was Marx’s first critical discovery, which allowed him to understand the logic and principles of the development of human society in the historic context.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770—14 November 1831) was a German philosopher and one of the most influential figures of German idealism. Hegel stressed the need to recognize that the realities of the modern state necessitate a strong public authority along with a populace that is free and unregimented. To Hegel, the principle of government was constitutional monarchy, the potentialities of which had been seen in Austria and Prussia in the 19th century.

Ludwig Andreas von Feuerbach (28 July 1804—13 September 1872) was a German philosopher, best known for his book The Essence of Christianity, which provided a critique of Christianity that strongly influenced generations of later European thinkers, including Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, Friedrich Engels, and Friedrich Nietzsche.

Feuerbach advocated dialectic materialism, or a method of reasoning that considers how things change, move, and are interconnected in the material world.

To Feuerbach, materialism is a philosophical view that posits that facts are dependent on material reality. Subsequently, the material basis of reality is constantly changing through a dialectical process. In his view, matter is prioritized over mind (consciousness); and scientific theory emphasizes the relative nature of theories about matter’s structure and properties.

Many of Feuerbach’s philosophical writings offered a critical analysis of religion. His thought was influential in the development of historical materialism and scientific atheism.

(2) The second intellectual source of Marx’s theory was English political economy. Having begun studying economic theory in the 1840s, Marx critically rethought and significantly reworked almost all previous economic theories, beginning with the 17th century, and concluded that it had reached its peak in the works of English economists Adam Smith and David Ricardo.

By creating his theories of value and surplus, Marx proposed and contrasted his economic interpretation to the theoretical principles of economic theory of Adam Smith, who called labor the source of value, and David Ricardo, who pointed out the opposition of interests of capital and labor.

Thus, the theory of surplus value became Marx’s second economic invention. Marx’s entire economic theory is based on the theories of value and surplus value. In other words, supply and demand is his key economic principle. The principle of supply and demand predicts that if the supply of goods or services outstrips demand, prices will fall. However, if demand exceeds supply, prices will rise. In short, in a free market, the equilibrium price is the price at which the supply exactly matches the demand.

In Marxist economic theory, the mode of production is a way of organizing society to produce goods and services. It’s made up of two main parts: (1) Forces of production—the tools, machines, raw materials, and other resources used to produce goods and services and (2) Relations of production—the social structures that regulate the relationship between people in the production of goods.

Marx believed that the mode of production was the foundation of society and that it demonstrated the differences between the economies of various societies. He also believed that the mode of production was a way for people to express their life, and that what people are coincides with what and how they produce.

According to Marx, capitalism is a mode of production that has been dominant since the 18th century. It’s based on private ownership of the means of production, the operation of the means of production for exchange value, and the need for people to sell their labor power to make a living.

(3) The study of the historical experience of the revolutions of the late 18th and 19th centuries, primarily the French Revolutions and the first revolutionary actions of the proletariat in European countries, gave Marx an understanding of the significance of class struggle in history. The ideas of utopian socialism of social structure of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier and Robert Owen, in which age-old dreams of equality and justice were refracted, served as the third source of Marxism and the basis for the creation of the principles of Scientific Communism by Marx and Engels.

In short, Marxism, and, in part, its outgrowth the far-left neo-Marxism (i.e., white privilege and critical race theory doctrines, DEI and systemic racism notion), includes dialectical materialism, economic theory of mode of production and the theory of Scientific Communism, including historical materialism.

Alexander B. Dolitsky was born and raised in Kiev in the former Soviet Union. He received an M.A. in history from Kiev Pedagogical Institute, Ukraine, in 1976; an M.A. in anthropology and archaeology from Brown University in 1983; and was enroled in the Ph.D. program in Anthropology at Bryn Mawr College from 1983 to 1985, where he was also a lecturer in the Russian Center. In the U.S.S.R., he was a social studies teacher for three years, and an archaeologist for five years for the Ukranian Academy of Sciences. In 1978, he settled in the United States. Dolitsky visited Alaska for the first time in 1981, while conducting field research for graduate school at Brown. He lived first in Sitka in 1985 and then settled in Juneau in 1986. From 1985 to 1987, he was a U.S. Forest Service archaeologist and social scientist. He was an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Russian Studies at the University of Alaska Southeast from 1985 to 1999; Social Studies Instructor at the Alyeska Central School, Alaska Department of Education from 1988 to 2006; and has been the Director of the Alaska-Siberia Research Center (see www.aksrc.homestead.com) from 1990 to present. He has conducted about 30 field studies in various areas of the former Soviet Union (including Siberia), Central Asia, South America, Eastern Europe and the United States (including Alaska). Dolitsky has been a lecturer on the World Discoverer, Spirit of Oceanus, and Clipper Odyssey vessels in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. He was the Project Manager for the WWII Alaska-Siberia Lend Lease Memorial, which was erected in Fairbanks in 2006. He has published extensively in the fields of anthropology, history, archaeology, and ethnography. His more recent publications include Fairy Tales and Myths of the Bering Strait Chukchi, Ancient Tales of Kamchatka; Tales and Legends of the Yupik Eskimos of Siberia; Old Russia in Modern America: Russian Old Believers in Alaska; Allies in Wartime: The Alaska-Siberia Airway During WWII; Spirit of the Siberian Tiger: Folktales of the Russian Far East; Living Wisdom of the Far North: Tales and Legends from Chukotka and Alaska; Pipeline to Russia; The Alaska-Siberia Air Route in WWII; and Old Russia in Modern America: Living Traditions of the Russian Old Believers; Ancient Tales of Chukotka, and Ancient Tales of Kamchatka.