When we last heard from our hunters headed to Unimak Island, they had made it to Cold Bay with one damaged airplane and one good one…and severe weather caused them to consider staying put for one night until things improved. This is part 4 of the 8-part serial of Chapter 1 of Lacher’s new book, which can be purchased at the links below.

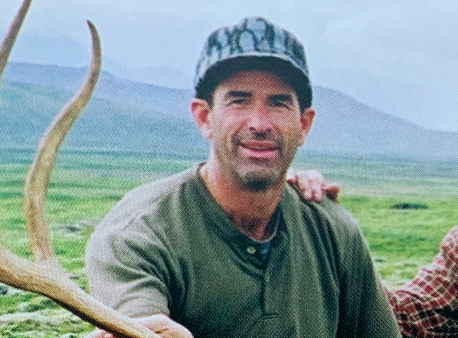

By BOB LACHER

Cold Bay is an interesting place. It rests on a narrow piece of volcanic real estate in the middle of nowhere. It’s also unusual in that it is a Caucasian rather than aboriginal community. Originally a WWII Air Force outpost, the NOAA weather station and Federal Aviation runway maintenance employees are mixed with a handful of PenAir employees along with a few U.S. postal employees to make a tiny town.

The Izembek National Wildlife Refuge staffs a small office there also. Ten to twelve children in school keep a single teacher occupied. A steady flow of migrant cannery workers head to Dutch Harbor or King Cove by going through the town during the fishing seasons.

The town also comes alive, in relative terms, during the spring and fall when hunters from all over the planet drop in for the world class waterfowl or to chase brown bears as large as any in the world. There is a small hotel and bar with a few rooms and a pay phone. The low roof, plywood wrapped, wind beaten structure also holds the town’s only grocery store, an establishment with mostly dried, canned or frozen food, whatever can be made consumable with a microwave or a hot plate.

Frank, dad and I fought against the wind to tie down our birds and then lugged some gear the couple blocks from the runway to the “hotel”. We rented a couple of $80 cubbies in the bunkhouse and headed for a room down the narrow hallway that was the makeshift grocery store.

Our big treat for the night would be microwave cuisine, some Hot Pockets and something that resembled pot pie with white cheese and chicken-bits-come-back-to-life. I resisted buying a can of Spam and dicing it up into a can of SpaghettiOs but it was tempting.

My final choices were determined entirely by what mixed well with Budweiser. I tried to visualize if the SpaghettiOs would sink in Budweiser or float. In the end I knew that for it to sink, it had to be greasy so I went with cheesy chicken pot pie. My only complaint was the frozen goo billed as the dough on the bottom never cooked and it took a little extra beer to swill the pasty globs down. I determined the heavy dough in the bottom of the pot pie to be a conspiracy, an extra thick filler snuck into the recipe to economize on both cheese and chicken bits.

The next day broke with less wind but still enough to make the plywood “hotel” creak and groan. After some instant coffee and a weather check we headed out to continue our excellent adventure. There was to be a temporary lull in the wind, down for most of the day, then back up to 40 plus by early evening.

In this part of Alaska if you waited for a windless day you may wait months. We’d take the somewhat quiet weather-window and try to fly the next 60 miles to Unimak and find some cover, behind a hill or in a draw, and set some good earth anchors, or fill some empty sand bags that we carry for the occasional tie down.

We also had lift-spoiling wing covers that could be pulled on the wings like stockings to help them from acting like a kite in a storm.

We crossed the scenic channel of ocean at False Pass after just a few minutes of flight time and made the shoreline again on the edge of Unimak and continued on. This channel is the first place going south that the Bering Sea meets and mixes with the Pacific Ocean. The views were magnificent. To our left some long shallow gorges, remnants of an old volcano being eroded, each lined with low green foliage interspersed with scree slopes of black volcanic rock. Straight ahead lay open plains with spotty high alder.

Repetitive small streams cut left to right, spilling off of the higher volcanic inclines and each heading to the ocean shores which dominated our view off to the right which was now the Bering Sea. The airplanes droned along in tandem, idle chatter on the radio, back and forth, pointing out this or that interesting landmark or topographical anomaly.

That weather window we hoped to squeak through must have been narrowing because the farther we went southwest the harder it seemed to be blowing. Within 30 minutes after liftoff we were almost to our planned destination but the gusts were mixing things up and causing some worry.

We were flying a crosswind course but I banked the cub right and directly into the wind for a quick and accurate check of the GPS ground speed verses indicated airspeed. The difference of the two numbers provided true wind speed and allowed us to determine what sorts of issues we may incur when trying to set down.

It was again cranking 35 with gusts to 45. Clearly we need to find cover to be able to set up any sort of tent camp and to be sure the airplanes could be safely anchored.

As we headed away from the volcanic foothills, the terrain was a mixed array of black sand blows, many long enough to land on, interspersed with rutted, undulating, vegetated flats. Frank and I spat observations back and forth on the radio, discussing the pros and cons of each long sand blow we found, cranking our birds around, swooping low to look over the dips and gullies and the banks formed upwind of the landing spots that may provide cover.

With each gust that slammed into the airplanes, and each heavy handed maneuver required to keep them flying true, the conversation became incrementally more serious.

It is often a fine line in such deteriorating situations, balancing the urgency to get the plane on the ground with the mental absolution that the place you have picked to finally put a noose on the madness is a good one. A quick consensus came together over the radios of which spots may be flat enough to land on, with cover, and within reasonable proximity to fresh water, something that is also necessary to have close to camp.

We picked a long and mostly smooth volcanic sand blow that was tucked in next to a large hill and ridge feature that spanned lengthwise on the windward side of the landing zone. It should have afforded a good wind block and it also had the bonus of a random, large volcanic boulder the size of a pick-up truck sitting half buried in the sand right where we wanted to park and set up camp.

With luck we could find a way to anchor the airplanes and the tent to the rock. Setting up for landing squarely into the 40 MPH wind, the ground speed was near zero at touchdown. Easing down like helicopters, both of us landed capably and taxied carefully over nearer to the boulder. We taxied with our tails high by pushing forward stick thereby forcing the big wing airfoils neutral to the wind.

The wind speed was right at a tipping point. If you set your parking brakes and jumped out, you had better be doing so with ropes in hand and trying to instantly get a wing snagged and then tied off to something stationary. Failing that, the aircraft would be trying to fly without you, alternately lifting one wing or another and bumping backward against the locked parking brakes. My Super Cub was more difficult to ground handle than the Maul since it took a little less wind to make it fly.

I had taxied in first and hogged the boulder, while my father and Frank took a position just behind me. I looked back and they were instantly out of the plane and furiously digging the Maul’s tires into the soft volcanic sand to lower the wind profile of the wings. Frank also readied some Duckbill earth anchors and a short sledge hammer to drive them.

Holding the airplane door tightly, I shoved it open into a howling gale delivering up a face full of blowing grit. I had sat in the airplane for a few moments to plan my moves and left it running just in case I had to gun it and lift off again if the plane was going to resist being ground handled and tied off.

My plan was to jump out with a fistful of ropes in hand and to quickly circle one all the way around the base of the big boulder and come off of that with a lead line for the right wing which I had pointed more windward than the other.

The left wing and tail would be handled by digging the tire in and then a couple of driven earth anchors. When I was trying to make the first tie for the right wing, from the looped rock to the wing strut, a forceful and sustained gust swept through and lifted the left wing three feet into the air and held it there, levitated as if by a magic trick.

What that meant was the entire aircraft was ready to go missing if the other wing got just a whiff more wind at the right angle.

Come back on June 11 for the next installment, Part 5: Camping in hurricane force winds, watching the planes — and Dad — levitate.

[Read Chapter 1, Part 1: A caribou hunt with my father, Unimak Island, 2004]

[Read: Part 2: No way to land an airplane]

[Read: Part 3: Bent wing and dead walrus on the beach]

Find this book at Barnes & Noble, Todd Communications, Title Wave Books, Once in a Blue Moose, and Amazon.