At 69 years old, John Kersbergen lives a humble and quiet life in Alaska, driving Uber part time in Anchorage. But 50 years ago, the former Navy boatswain’s mate was in the middle of one of the most chaotic, heartbreaking, and heroic moments in American military history: the fall of Saigon.

He was just 17.

In April 1975, as the Vietnam War reached its devastating end, Kersbergen was stationed aboard the USS Midway, an aircraft carrier home-ported in Yokasuka, Japan, that would become central to one of the largest helicopter evacuations in history — Operation Frequent Wind. He had grown up rough: dropped out of school, ran away from home, and fell in with a bad crowd. His father, a Navy veteran himself, delivered a hard truth: “Son, you’re either going to find yourself in jail or dead.” So Kersbergen enlisted.

Too young for the Marines or Army, the Navy took him in. He finished boot camp in 1973, and by 1974 he was aboard the Midway, working as a refueler in Japan, handling JP-5 jet fuel with a smell so toxic it clung to him no matter how often he showered. It left his skin raw and may have contributed to the neuropathy and prostate problems he developed later in life — although the VA acknowledged he was exposed to Agent Orange.

He remembers the mission orders as if it were yesterday. “We were in the Sea of Japan, heading home to Yokasuka, when the captain came over the loudspeaker and said we were being rerouted to the Gulf of Tonkin, with a stop in the Philippines first,” he recalled. “We had to offload all the fighter jets — F-4 Phantoms, F-14s Tomcats, A-6 Intruders, and A-7 Corsairs — and bring in helicopters, Hueys, H-47s, Chinooks, and Cobras. He couldn’t tell us the mission until we got there.”

The mission was clear soon enough: evacuate American personnel and Vietnamese allies as Saigon fell.

One of Kersbergen’s battle stations was what’s called Sponson Watch. With high-powered binoculars and plugged into the ship’s tower communications, he stood watch in full battle gear, including a breathing apparatus strapped to his chest in case of a chemical attack. His job: monitor the skies and the embassy, report any helicopters shot down, and help coordinate rescue efforts for survivors in the water.

But nothing could prepare him for what he saw through those lenses.

“I would pan over to the streets of Saigon, and there were women and children being hacked to death with machetes and shot in the back of the head,” he said, his voice heavy. “More people were slaughtered during the evacuation than in the whole 11-year war. The Viet Cong hated the South Vietnamese even more than us — they saw them as traitors.”

He wiped away tears in real time, helpless as the horror unfolded before him and knowing there was nothing he could do to help them. “The Viet Cong were like locusts going through a corn field.”

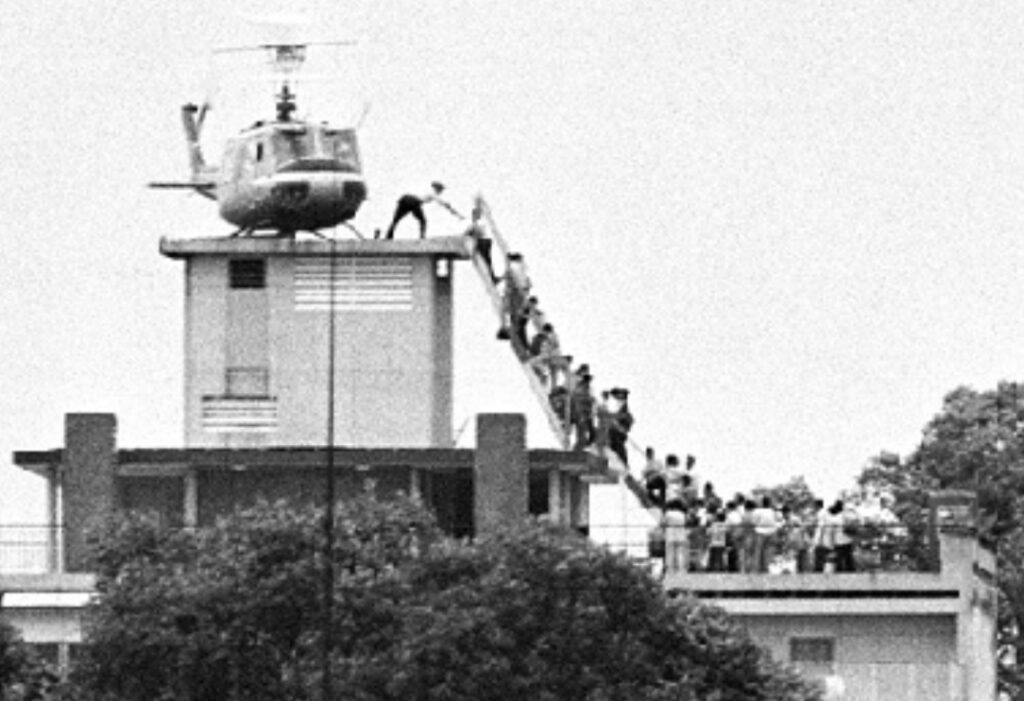

The helicopters came in constant waves, picking evacuees off the embassy rooftop and ferrying them to the Midway. Kersbergen and his shipmates helped rig a makeshift Jacob’s Ladder out of cargo nets and pallets, lowering it over the ship’s edge to rescue women and children climbing from fishing boats that were pulling alongside the carrier, overflowing with desperate refugees.

Between monitoring the skies and hauling people out of the water, the young sailor moved through the ship’s crowded hangar bay, tiptoeing between the bodies of crying children and terrified families.

Then came the “bird dog.”

A small, fixed-wing aircraft approached the Midway. — a two-seater O-1 Bird Dog piloted by a South Vietnamese officer carrying his wife and five children, including a baby. The plane had no arresting hook, no way to stop on a carrier deck. As it approached under enemy fire, the pilot dropped notes onto the deck — tied with rocks and fastened with rubber bands explaining his situation and asking permission to land. The first two notes blew over the deck but the third note made it. The pilot was requesting that room be made on the deck for him to land.

The Midway’s crew assembled a makeshift crash net at the catapults at the end of the flight deck, where jets are usually launched into the air. They pushed helicopters into the ocean to make room. The captain aimed the ship into the wind. Everyone on the deck held their breath. The plane touched down, bounced — once — and somehow came to a stop. Everyone present broke into cheering.

Out stepped the Vietnamese pilot. Then his wife with babe in arms. Then one child after another, seven people in total.

“We gave them cookies and candy and treated them like rock stars,” Kersbergen recalled. “After all the people we couldn’t save, here was one whole family we did save. That was everything.”

The aircraft they escaped in is now on display at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida.

But even after the evacuation, the trauma lingered. “The guilt I’ve carried for all the people we had to leave behind,” Kersbergen said. “Telling them we’d come back and knowing we never did — it was too dangerous. Knowing they were probably slaughtered.”

Then, nearly five decades later, came a moment of grace.

While driving for Uber in Anchorage, Kersbergen picked up a quiet Asian man at the airport. As they drove, the man noticed Kersbergen’s USS Midway cap.

“Did you serve on the Midway?” the man asked.

“Yes,” Kersbergen replied.

“Were you there in April of 1975?”

Again, yes.

The man paused. “I want to thank you,” he said. “My grandmother was one of the evacuees.”

Kersbergen, stunned, asked: “Did she come from the top or below?” — a reference to whether she’d arrived by helicopter or from the boats, climbing up that cargo net.

“Below,” the man answered.

That was all Kersbergen needed to hear.

At that moment, he realized he may have been one of the members of the team who helped save the man’s grandmother, a teenage girl at the time, the only member of her family to survive. The rest — her parents, siblings, aunts, uncles — were slaughtered by the Viet Cong. She had told her story countless times to her grandchildren in California so they would understand the price of their freedom.

“She told me never to take this country for granted,” the man said. “I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for you.”

Both men broke down in tears.

“For years, I had wondered if I made a difference,” Kersbergen said. “And in that moment, I knew. I did. I helped save a life.”

Fifty years later, the memories still haunt him of the chaotic evacuation of Saigon. But now, thanks to one simple Uber ride, John Kersbergen knows he also left Vietnam with something else—hope.

Learn more about the fall of Saigon in April, 1975, at this State Department link.