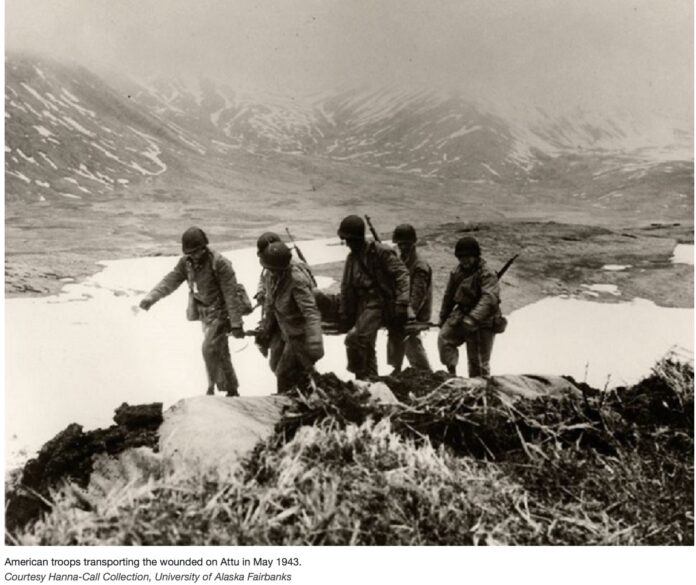

Editor’s note: 549 American fighters were killed in battle, some of it hand-to-hand combat. Another 1,148 were wounded, and 1,200 suffered severe injuries from cold weather during the retaking of Attu in the Western Aleutians. Another 614 American soldiers died from disease and 318 from Japanese booby traps, friendly fire, or accidents. In 1943, the US Army’s 7th Infantry Division recaptured Attu as a part of removing Japanese occupiers of American soil, the second-deadliest battle for Americans in the Pacific after the Battle of Iwo Jima.

“The loyal courage, vigorous energy and determined fortitude of our armed forces in Alaska—on land, in the air and on the water—have turned back the tide of Japanese invasion, ejected the enemy from our shores and made a fortress of our last frontier. But this is only the beginning. We have opened the road to Tokyo; the shortest, most direct and most devastating to our enemies. May we soon travel that road to victory.” – Lieutenant General Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr., after the Aleutian Islands campaign

“It was rugged…the whole damned deal was rugged, like attacking a pillbox by way of a tightrope…in winter.” – Lt. Donald E. Dwinnell

“The ones who suffered were the ones who didn’t keep moving…. They stayed in their holes with wet feet. They didn’t rub their feet or change socks….” – Captain William H. Willoughby

By JOEY BALFOUR | NATIONAL WORLD WAR II MUSEUM

After occupying the Western Aleutian Islands of Attu and Kiska in June 1942, the Japanese forces on those islands were supplied by convoys from bases in the Japanese Home Islands and on the island of Paramushiro. To stem the flow of supplies to the enemy garrisons the US Navy set up a blockade. On March 26, 1943, one of those supply convoys was intercepted by a task force under the command of Rear Admiral Charles “Soc” McMorris.

The warships escorting the Japanese convoy outnumbered the American task force by two to one in heavy ships, but that did not stop McMorris from engaging them. At 8:42 a.m., the heavy cruiser USS Salt Lake City (CA-25) fired a salvo of 8” armor piercing shells at the Nachi, the flagship of the Japanese convoy. Almost simultaneously, the Nachi replied with a salvo of her own. The Battle of the Komandorski Islands had begun.

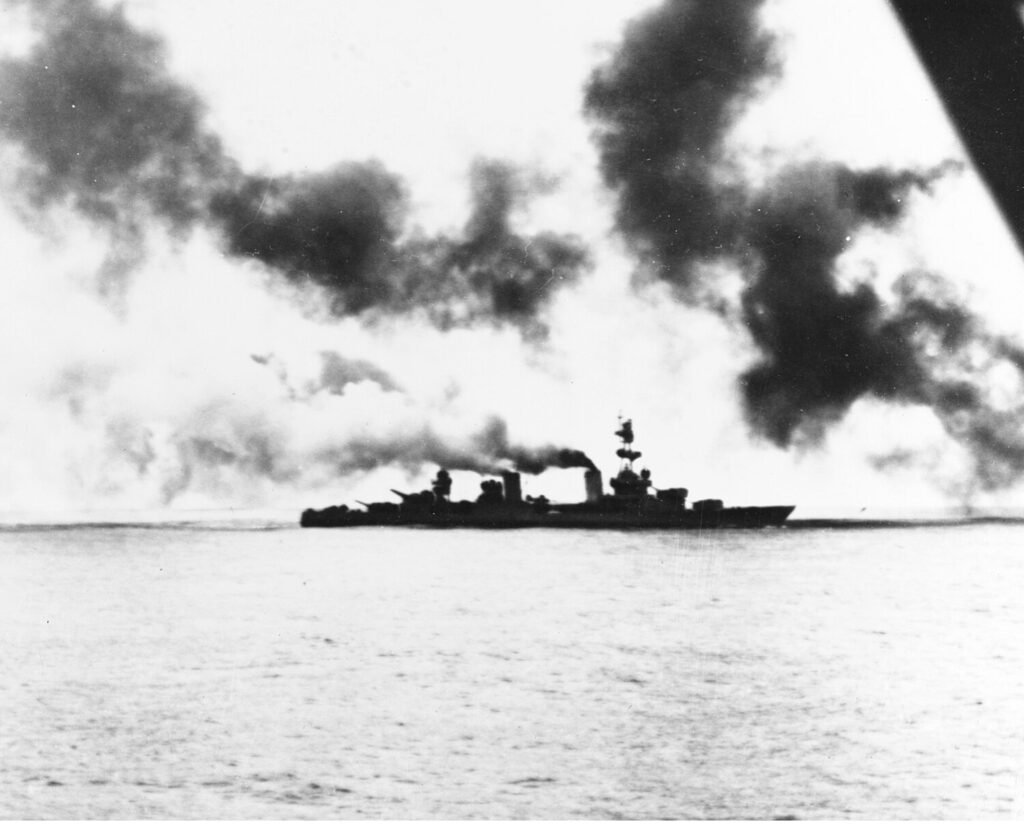

The battle lasted nearly three and a half hours. During the melee, the Salt Lake City was hit several times by 8” shells. Sea water pouring in through holes in her hull polluted the ship’s fuel and extinguished her boilers, causing the ship to go dead in the water. With fuel oil spilling out of a ruptured bunker, Machinist’s Mate 2nd Class James F. “Fran” McCorriston, at his general quarters station in one of the ship’s engine rooms, thought: “if the Salt Lake City took another hit she would have become the first cruiser on the moon.”

with an enemy salvo landing astern. Photo credit: U.S. Navy

Destroyers quickly laid a smoke screen to shield the Salt Lake City, then turned on the Japanese ships which had continued to close the distance between them. The American destroyers launched a valiant, but ineffective, torpedo attack. The Japanese warships continued to close on the American task force which they now had on the ropes.

The American ships were in trouble. The Salt Lake City was dead in the water and only able to fire guns in one of her main battery turrets. McMorris’s other cruiser, the light cruiser USS Richmond (CL-9), was 30 years old and her 12 6”/53 caliber main battery guns were no match for Japanese Admiral Hosogaya’s two heavy and two light cruisers barreling down on the American task force.

Then, in a move that stunned McMorris and every American sailor with him, the Japanese warships broke contact shortly after noon and retreated from the battle area. Many theories abound as to why the Japanese broke contact, but whatever the reason, the March 26, 1943 Battle of the Komandorski Islands marked the last attempt by the Japanese to resupply Kiska and Attu by convoy for the remainder of the war. It was also the longest naval gun battle of the war and the last pure ship-to-ship battle in modern naval history.

By May 1943 the US Army Air Forces, along with elements of the Royal Canadian Air Force, had been bombing and strafing Japanese positions and facilities on Kiska and Attu on a somewhat regular basis. In addition to these aerial attacks, American naval vessels, ranging in size from submarines to battleships, had been bombarding the enemy held islands for months. Now, it was the Army’s turn.

On the morning of May 11, 1943, the US 7th Infantry Division landed on Attu and began driving inland from the invasion beaches. Over the next 19 days, the American troops ashore would fight for every inch of ground gained against a determined enemy, through some of the harshest combat conditions of the entire war.

The 7th Infantry Division had been shipped to the Aleutians soon after completing desert training. In order to conceal their destination, which was assumed to be North Africa, no specialized cold weather gear was loaded aboard the transports. When the GIs went ashore on Attu they were wearing the same uniforms and carrying the same equipment they had trained with in the California desert. During the three weeks of fighting on Attu the temperature rarely went above 40° Fahrenheit.

Those combat and support troops who went ashore after the initial invasion were better equipped to handle the cold, but frontline infantrymen like Lieutenant Stanley Wolczyk—the commander of 1st Platoon, Company G, 32nd Infantry Regiment—were forced to strip the cold weather gear off of the dead.

Even though taking gear from a dead soldier somewhat repulsed Wolczyk, he and his men were forced to do it anyway. Referring to the act, Wolczyk said, “if they happen to die, our fellows would steal their jackets, their parkas, and their boots. Can you imagine stealing? Not stealing but the poor soldier couldn’t use it anymore, and we could have some benefit from these people bringing it in.”