By ALEXANDER DOLITSKY

According to prominent American sociologist Joseph Elton, “Acculturation is the adoption of cultural traits, norms and customs by one society from another… There is no clear line [that] can be drawn between acculturation and assimilation processes. Assimilation is the end–product of a process of acculturation, in which an individual has changed so much as to become dissociated from the value system of his group, or in which the entire group disappears as an autonomously functioning social system.”

Acculturation and assimilation to a new culture by newcomers is a personal and self-determined process—the right to make one’s own decisions without interference from others. No one can force a newly arrived legal and properly vetted immigrant to accept the cultural traditions, lifestyle, and customs of his/her new country. The newcomer himself must see a socio–economic necessity and benefits in accepting new traditions and values to ultimately embrace and accept his/her new culture without external influence.

Indeed, language, religion, education, economics, technology, social organization, art, appearance and political structure are typical categories of culture. Culture is a uniquely human system of habits, moral values, and customs carried by the society from one’s distant past to the present.

True, for a newcomer’s adaptation, these socio-economic and cultural categories are essential for survival in a foreign environment. Nevertheless, changing/adapting people’s behavior (e.g., temperament, manners, demeanor, gestures, conducts, actions, bearing, comportment, preferences, motivation, ambition, etc.) is the most critical obstacle for acculturation and assimilation to new cultural traditions. To assimilate to a new socio-economic environment, newcomers often face culture shocks, as I did in my early days in the United States.

I was born and raised in an internationally isolated, socially closed and predominantly Caucasian socialist society—Kiev, former Soviet Union. While riding public transportation in Kiev, I would occasionally be in the presence of a student from Africa and, as everybody else, I would stare at this person with an epistemic curiosity. In fact, it was only upon my arrival to the United States (Philadelphia) in February of 1978 that I, for the first time, interacted with black people and other ethnic minorities daily in various public places; I have not had any preconceptions about or prejudice toward blacks or other ethnic groups in America—absolutely none.

Initially, as a young emigree in my mid-20s in the United States, I held various menial minimum-wage jobs: I shoveled snow, painted houses, assisted in various construction projects, washed dishes and served customers in the restaurants, and participated in several archaeological projects for Temple University, etc.

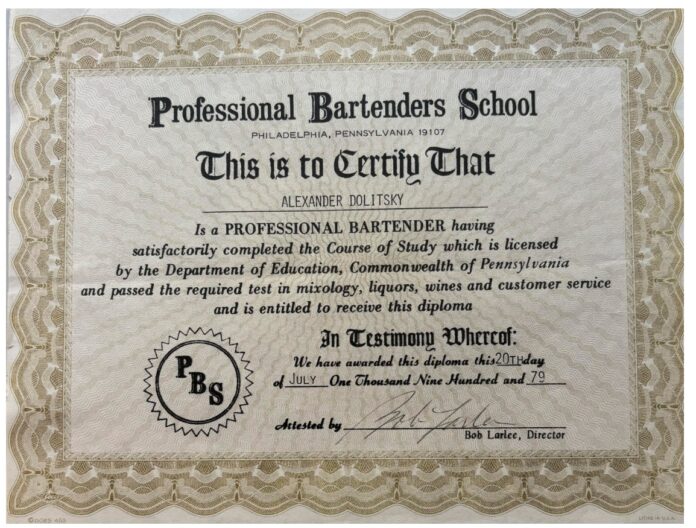

In 1979, I successfully completed the course of study in mixology and customer service and passed all necessary tests given by the Philadelphia Professional Bartenders School.

Soon after my completion of the bartender school, I was called for an interview in one of the unassuming bars in southwest Philadelphia, a large area encompassing Philadelphia International Airport and several residential districts, with streets lined with row houses. Southwest Philadelphia’s demographics included a large West African community and a population that was about 70% black, 25% white, and 5% Asian.

Upon arriving for the interview in the early afternoon, the owner of the bar (middle-aged black man) greeted me and briefly checked my credentials. “You must be a qualified bartender,” he acknowledged, glaring directly into my eyes. “But look around you, what do you see?” he continued, pointing to the surroundings. There were 5-6 black customers in the smokey bar observing the scene of the interview. “You will never make it here, you don’t belong here,” declared the owner. He then showed me to the door.

A week later I found a bartending job in the Greek “Dionysus Restaurant” in Society Hill, which is nestled in the heart of historic Philadelphia, a picturesque enclave known for its well-preserved Georgian and Federal-style homes. For about a year, I sincerely enjoyed my work, as well as my humorous Greek coworkers, traditional Greek dancing, generous customers, delicious food and the authentic environment of the restaurant until I departed for the Graduate School of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island in the Fall of 1980.

In 1983, after receiving my M.A. in anthropology from Brown University, I was enrolled in the Ph.D. program in anthropology at Bryn Mawr College until the Summer of 1985. Bryn Mawr is located on the Main Line of the western suburbs of Philadelphia along Lancaster Avenue. It is a long-established upper-middle class area, incorporating small cities of Overbrook, Merion, Narberth, Wynnewood, Ardmore, Haverford and Bryn Mawr.

My stipend at Bryn Mawr College was only $400 per month; I had to supplement my income by working the night shift as a security officer at the Bryn Mawr College and as a waiter in a small restaurant in Ardmore for several hours in the early afternoon. The restaurant in Ardmore was owned by a Jewish family and mostly visited during lunch hours by middle-aged and elderly white customers from the neighboring Main Line cities. The ambiance in the restaurant was pleasant and the food was delicious.

Frankly, I was a lousy waiter; I was always tired after my night shift and mentally preoccupied with my studies. However, my coworker, a young black man in his early 20s, was a thorough and energetic waiter. He was quick, clean, disciplined, punctual, served customers efficiently and remembered all items in the menu from A to Z. He was also a hard-working student at the Philadelphia Community College. In observing this young man and his work ethic, I could predict that he was going to succeed in life and fulfill his dreams and aspirations. And, eventually, regardless of his race and ethnic background, all doors would be open for him in our country.

Indeed, the process of acculturation and assimilation can be long and turbulent for many legal newcomers. It is critical, therefore, for American society to be inclusive, tolerant, and educated in cross–cultural communication to welcome legal and properly vetted newcomers to our multi-ethnic and exceptional country.

Alexander B. Dolitsky was born and raised in Kiev in the former Soviet Union. He received an M.A. in history from Kiev Pedagogical Institute, Ukraine, in 1976; an M.A. in anthropology and archaeology from Brown University in 1983; and was enroled in the Ph.D. program in Anthropology at Bryn Mawr College from 1983 to 1985, where he was also a lecturer in the Russian Center. In the U.S.S.R., he was a social studies teacher for three years, and an archaeologist for five years for the Ukranian Academy of Sciences. In 1978, he settled in the United States. Dolitsky visited Alaska for the first time in 1981, while conducting field research for graduate school at Brown. He lived first in Sitka in 1985 and then settled in Juneau in 1986. From 1985 to 1987, he was a U.S. Forest Service archaeologist and social scientist. He was an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Russian Studies at the University of Alaska Southeast from 1985 to 1999; Social Studies Instructor at the Alyeska Central School, Alaska Department of Education from 1988 to 2006; and has been the Director of the Alaska-Siberia Research Center (see www.aksrc.homestead.com) from 1990 to present. He has conducted about 30 field studies in various areas of the former Soviet Union (including Siberia), Central Asia, South America, Eastern Europe and the United States (including Alaska). Dolitsky has been a lecturer on the World Discoverer, Spirit of Oceanus, and Clipper Odyssey vessels in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. He was the Project Manager for the WWII Alaska-Siberia Lend Lease Memorial, which was erected in Fairbanks in 2006. He has published extensively in the fields of anthropology, history, archaeology, and ethnography. His more recent publications include Fairy Tales and Myths of the Bering Strait Chukchi, Ancient Tales of Kamchatka; Tales and Legends of the Yupik Eskimos of Siberia; Old Russia in Modern America: Russian Old Believers in Alaska; Allies in Wartime: The Alaska-Siberia Airway During WWII; Spirit of the Siberian Tiger: Folktales of the Russian Far East; Living Wisdom of the Far North: Tales and Legends from Chukotka and Alaska; Pipeline to Russia; The Alaska-Siberia Air Route in WWII; and Old Russia in Modern America: Living Traditions of the Russian Old Believers; Ancient Tales of Chukotka, and Ancient Tales of Kamchatka.

Always interesting, engaging and intriguing. Having met and conversed with Professor Dolitsky on many occasions, I have found him to be what I would describe as an archetypical American. He has embraced the idea of America. After all, our republic is, essentially, an idea… expressed in the parchment we call our Constitution. And, truly embracing that beautiful idea is the essence of being an American. Professor Dolitsky, having immigrated from a relatively more oppressive culture, demonstrates exceptional appreciation for the beautiful idea that is America. Accordingly, I view him as more American than most of us born and raised here who take our status for granted. Carry on Professor…. and may you be blessed as a fellow American.

Iv’e always had this sorta animosity towards people that would leave their home country and go to where the grass is greener instead of making their home country better even though that may be difficult.

3rd Generation, regardless of your heritage, somewhere in your past your ancestors migrated to this continent. Therefore, you are privileged to enjoy the best civil rights protections in the history of the world because your ancestors “left their home country and go to where the grass is greener.”

Then lets just invite everyone from all over the world to the U.S. abandoning their home country’s and breed to oblivion, then abandon the U.S. to seek a greener pasture, but wait, there are no more greener pastures left.

My ancestors came here when America was a wilderness frontier, scarce of people, fought in wars and did not feed off tax payers money.

My article is about LEGAL and properly VETTED newcomers to the US.

Thanks for the reply and I’m glad you are here and I have no doubt that you are an asset to our country. I need to watch my manners.

I have illegals competing with my contracting business who have not the legal credentials, trade requirements and there’s also the border crises.

3rd Generation Alaskan,

You have an interesting perspective for a person whose family left your home country a few decades ago, to come to Alaska because the “grass was greener” and with tens of thousands of other outsiders, destroyed these lands now called Alaska.

We would be better off if your grandparents stayed wherever they migrated from and made that place better, even though it was difficult.

Brian, I wrote my comment to the 3rd Generation Alaskan and placed it incidentally under your name. My apologies.

According to immigration laws of the United States, four groups of people are not allowed to immigrate to our country: economic immigrants, mentally ill individuals, people with criminal records, and members of the Communist Party. My, yours, Wayne and Brian opinions are irrelevant for this case. We must comply with the laws of our Land. Period.

Only political refugees can enter the country legally. I left the former Soviet Union in 1977 and arrived in the United States in February of 1978 under the political refugee program. I wrote several articles on this subject that were published by MRAK. Please check the MRAK’s archive for my articles relevant to this subject.

Not specifically mentioned was making stuff up about Haitian diets when assimilating immigrants

Genetics create culture.

Alex,

Originating from the former Soviet Union you probably were not a “good” bartender. Americans for incomprehensible reasons like nasty tasting, watered downed effiminate beverages.

The Eastern European tradition for men of taking 3 straight water glass sized shots of quality vodka, of which there is nothing comparable here in the states, in the company of solid friends, is infinitely more enjoyable. There is no need for a “bartender”.

There was a historical period lasting a century or so, that America attracted immigrants who yearned to assimilate into the concept of an American culture. You are one of these, and have the benefit of a quality education obtained overseas. Which allows you to analyze and articulate issues clearly.

Our youth does not have access to education. An educated public, with direct multi generational family support, private ownership of family businesses and farms, grounded in Christian faith is the threat that had to be eliminated to consolidate power by what are called our “leaders”.

What was created through sacrifice, hard work and attributed to the Grace of God is gone. American society has degenerated rapidly into a self centered, uneducated and moral decadence.

The American people now meekly accept state and federal totalitarian governance, led by incoherent imbeciles.

Your perspective as an immigrant to a foreign land of acculturation and assimilation is the reverse experienced by Alaska Natives.

Our grandparents generation had to acculturate and assimilate into the culture of immigrants who showed up on our lands specifically to exploit the abundant resources. Literal “get rich quick” desperation.

The narrative the immigrants used to justify their exploitation was based on asserting Natives were technologically primitive, illiterate, ignorant and culturally inferior.

Which was mostly factual, with the fatal exception that the hybrid, short term American culture has already disintegrated in less than 200 years.

Now we struggle to educate our youth concerning their abandoned extended family based culture, which was effective for societal preservation lasting thousands of years.

Insightful thoughts, Brian. Yes, I was a lousy bartender and waiter. You are correct, East Europeans do not mix drinks. But bartending is paid better than painting houses. I had to support and re-educate myself to achieve my dreams and aspirations in the US.

My bartender comment was meant to point out one of the multiple ironies your post illustrates, in a light hearted manner.

As an already highly educated and productive immigrant, you still had to start from scratch.

The European, including Soviet academic standards of higher education in the time frame posted on your biography were much higher than here in the US.

While Western European and American academic standards and priorities have slide to what amounts to the promotion of useless, blatant demagoguery, in the east advanced engineering and other useful disciplines excel.

There was absolutely no intent to minimize the value of bartenders or skilled culinary industry service providers.

Our society has been centrally managed to supress innovation, and create a hereditary ruling class with the masses in a state of perpetual servitude.