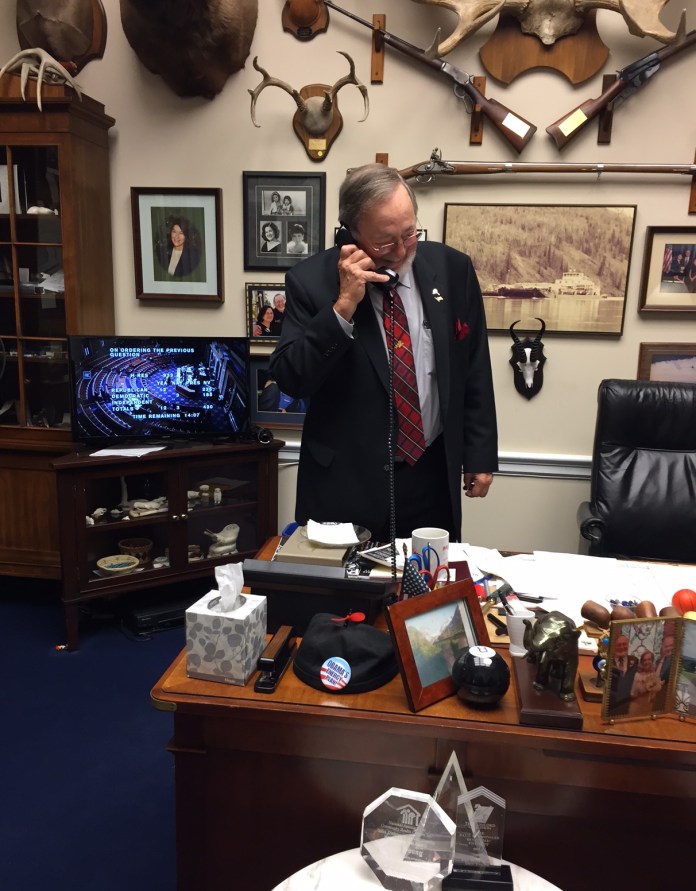

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Rep. Don Young is holding forth, as he does. He’s telling the story of an Alaska harbor master who wants to install a buoy in the harbor for safety. But the harbor master has to get separate permits from the U.S. Coast Guard, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the EPA.

And then he has to get State permits from the Departments of Natural Resources and Fish and Game. He’s working on five permits for one small buoy.

“And it’s a buoy! It’s for safety!” Rep. Young exclaims, throwing up his hands at a bureaucracy that has become Kafkaesque.

Young has been beating on the permitting-abuse drum for decades. It’s a constant theme of his because Alaskans call his office nearly daily with the most outrageous tales of federal bureaucracies run amuck.

“It shouldn’t take calling your congressman to get relief from the federal bureaucracy, but that is often the route citizens end up having to take,” said Matt Shuckerow, press secretary to Young. “A call to an agency from a member of Congress — that’s something they don’t like to get.” But it’s also the type of call Young and his staff have to make on behalf of Alaskans on a regular basis to get things moving for people who are trying to accomplish the simplest of tasks.

THE PERMITTING ACT THAT SWALLOWED THE ECONOMY

The extravagant expansion of the federal permitting process has created an entire industry that for decades has gummed up the works of critical infrastructure projects and ground progress to a halt.

“The National Environmental Policy Act is the mother of all environmental laws,” said John MacKinnon, executive director of Associated General Contractors of Alaska. Take the Juneau Access Project, which started the NEPA process back in the early 1990s.

“You have to select a ‘preferred alternative’ and if that alternative involves wetlands you need an Army Corps of Engineers permit. But the Corps says they have to look at ALL alternatives so they can choose the one that has the least damaging and still practical alternative. That means you have to start the process all over again,” MacKinnon said, bringing out a graphic he shows during presentations to illustrate the epidemic growth of permitting requirements:

It’s only gotten worse under the Obama Administration, with the environmental lobby having taken over the Department of Interior, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Forest and Park Services.

Everything from buoys to bridges are now held up by the overzealous permitting regulations. NEPA, once a simple law that required environmental impact statements, has grown into thousands of pages of regulatory burden as a result of its ambiguously broad mandate.

NEPA’s requirement that projects complete environmental impact statements before taking major action has given nearly unlimited power to both the federal bureaucracy and environmental organizations, as illustrated by Juneau Access Project, now closing in on a quarter of a century of delays.

SULLIVAN TAKING UP THE CHALLENGE

Rep. Young has a counterpart in the Senate who shares his concerns and is uniquely positioned in a committee to do something about it.

U.S. Sen. Dan Sullivan, who has advocated for the Juneau Access Project, is developing a bill that will unwind some of the major problems NEPA has created.

[READ: How to put building permits on fast track]

Sullivan has also been talking with President-elect Donald Trump about the need for federal permitting reform in order to jumpstart jobs and rebuild the nation’s aging infrastructure.

The draft of the bill will only be able to reflect what is the purview of the Subcommittee on Fisheries, Water, and Wildlife that he chairs in the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works. His staff is delving deep into topics like wetlands mitigation, which has become costly and impractical in Alaska, with its more than 170 million acres of wetlands.

“When we wanted to build a middle school in Juneau, there were pockets in the forest that were the size of potholes, but they decided to call it a forested wetlands,” explained MacKinnon, who used to serve on the Juneau Assembly. “We need to dial down the mitigation on wetlands. It’s gone from costing $10,000 per acre on the North Slope to almost $50,000. It’s extortion.”

One way to lessen the burden of NEPA would be to put in place a set of categorical exclusions, but to do so without also creating another new layer of study requirements that would be open to abuse by the environmental lawsuit industry.

“Forty years ago, the biggest problem we had was trying to find the money to build something. Today our biggest obstacle is getting permission,” MacKinnon said.

With both Rep. Young and Sen. Sullivan committed to permitting reforms, and with a new pro-business president taking the oath of office, the rewrite of federal permitting laws and regulations is tantalizingly close.